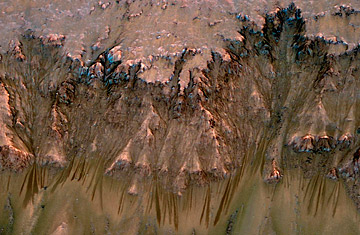

A combination image made with 3-D modeling illustrates possible evidence of liquid water active on Mars today.

(2 of 2)

Just as important as the presence of the water is the overwhelming evidence that it's salty — a key feature of the seawater in which Earthly life emerged. Salt exists in deposits and dustings over much of the surface of Mars, which is consistent with a world that was once so watery. What's more, while ordinary water could not flow at temperatures below 32 F (0 degrees C), densely concentrated salt water has a much lower freezing point, making it possible for it to remain liquid deep into the mid-latitude's lower temperature ranges. So concentrated may this Martian brine be that it would actually flow more like syrup than water.

Just what shape the subsurface water deposits might take is impossible to say with certainty, but Lisa Pratt, a mission scientist, thinks there's a lot to learn from the closest Earth analogs we have to this part of the Martian surface: the Siberian permafrost. There, she says, subsurface water collects either in fracture networks or in small pockets called cryopegs. Once the Martian water grows warmer and begins to leak out of these deposits, it would seep up first to what's known as a photic zone, a think film of surface soil where warmth from the sun could allow biological activity to take place.

Not every instrument aboard the MRO agreed entirely with the findings of the cameras. The ship's spectrometer, which would be expected to find the elemental signature of water when it scanned the rivulet zones, came up empty, but that could simply be a matter of timing. Atmospheric pressure on the surface of Mars is just 1% of what it is at sea level on Earth. Even in the biting cold, this would cause fresh water simply to boil away.

"Salty water wouldn't boil," says MRO team member Alfred McEwen, "but it would evaporate very quickly." By the time the spectrometer could take a bead on the streaks, the water that formed them would be gone.

JPL is already planning Earth-based experiments in which soil and brine of similar composition can be studied for clues to exactly what's going on Mars. A European-American Missions set to launch in 2016 will orbit Mars looking for trace gas emissions, particularly methane and oxygen molecules, both of which could be the byproducts of biological processes. The Curiosity rover, a Mars car about the size of an SUV, will launch in November as well, but NASA cautions that it won't be able to investigate the sites up close. Its planned landing site is too far from where the streaks have been seen and it was not built to navigate the steep, 35-degree slopes where the rivulets are forming.

There is one other reason — known as a "planetary protection concern" — that even a properly designed, perfectly targeted Curiosity would not be allowed to set so much as a wheel near the newly discovered sites. The rover has not been fully sterilized in a way that would ensure no Earthly bugs could commingle with or contaminate Martian organisms, and it can't be redesigned now in a way that would even make such a biological scrubbing possible.

It's an admitted shame that our next great Mars traveler will have to give such a wide berth to the planet's newest great site — but the reason for that avoidance is tantalizing all the same. The search for extraterrestrial life just took a small but very important step forward — not half-bad for a nation that a week ago couldn't even get along with itself.