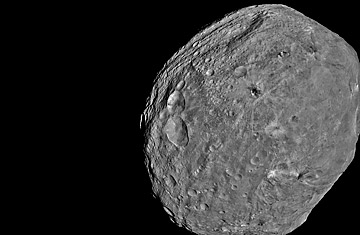

NASA's Dawn spacecraft obtained this image of the giant asteroid Vesta on July 24, 2011

Correction Appended: August 8, 2011.

In most cases, the moment a space probe goes into orbit around a celestial object is a nail-biter, with engineers and scientists nervously checking their monitors to make sure hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars haven't just vanished into the ether. But when the Dawn spacecraft slipped into orbit around the asteroid Vesta two weeks ago, chief engineer and mission manager Marc Rayman of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory said at a press conference on Monday, "I was out dancing."

He was just that confident that Dawn would surrender itself to the gravity of the solar system's second largest asteroid without a hitch — and the photos that are starting to stream back from more than 100 million miles (160 million km) away are proof that the taxpayers' money has indeed been well spent. Dawn won't get into serious photography until next week, when it spirals into a survey orbit at 1,700 miles (2,700 km) for a comprehensive mapping run, but the images the ship's cameras have captured from more than twice as far away are already blowing scientists minds.

"What's the most surprising thing we're seeing?" Dawn principal investigator Chris Russell, from UCLA, asked himself. "It's like asking 'Who's your favorite child?'" High up on the list is a series of giant parallel grooves that runs for hundreds of miles flanking Vesta's equator. "The grooves are neat," said Russell simply. It's not certain how they formed, but the scientists have a pretty good idea: eons ago, a giant object smashed into Vesta's south pole, in what Russell calls "almost a body-shattering event."

The collision reshaped Vesta's southern hemisphere, which to this day looks far smoother than the heavily cratered north, and sent megatons of rubble flying into space. About 5% of the meteorites that fall to Earth were originally part of Vesta. The impact may also have squeezed Vesta like an accordion — and the grooves may have formed when the asteroid partially rebounded. "This is just speculation," cautioned Russell, promising that a better answer will have to wait until Dawn can spend some time looking closer.

That more-intimate look will also presumably help scientists understand another of Russell's favorite children: a vivid set of alternating dark and light markings inside some of the asteroid's craters. "I never saw anything like that before," he said.

As Dawn takes up an increasingly tight set of orbits — the closest, which will begin several weeks from now, will bring the probe to within 125 miles (200 km) of the surface — the onboard neutron and gamma-ray detectors will get a chance to analyze Vesta's surface mineralogy in detail. Subtle changes in the probe's altitude as it moves through the asteroid's gravity field, meanwhile, will reveal something about Vesta's subsurface structure. That matters because the asteroid is one of the oldest known objects in the solar system, having formed a mere 5 million years after the solar system started to congeal. Any information Dawn sends back over the next year could thus help planetary scientists understand what the conditions were like when the Earth itself began to take shape, and how that process unfolded.

There's plenty more. Dawn's infrared mapping spectrometer has shown that some parts of the surface absorb heat much more readily than others. No one knows why. In addition, the giant impact that squashed Vesta removed a layer of surface rocks, and later, smaller impacts excavated even deeper into the south polar areas; scientists can't wait to look at the underlying materials that are now exposed to their view. And Russell wants to get a peek at the opposite pole as well. A major impact would have sent shock waves through Vesta, which would have converged in the far north. "I'm really anxious to see how that energy was focused," he said.

Finally, there are the surprises nobody has even anticipated, which may well reveal themselves as Dawn moves closer to the asteroid. But even when those are exhausted, the fun won't be over. Next July, the probe will fire up its ion-propulsion engines and head out into space once more, en route to a 2015 rendezvous with the asteroid Ceres — the biggest member of the asteroid belt and (thanks to a contentious 2006 decision by the International Astronomical Union) a member, with Pluto, of the newly created category of dwarf planet.

Some scientists even think Ceres, like Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's Enceladus, may harbor liquid water under its icy surface. Investigators will know better in a few years, after they've had a chance to analyze all of the data they collect. For now, they're plenty happy just doing that collecting.

The original version of this story incorrectly spelled the mission manager's first name. The proper spelling is Marc.