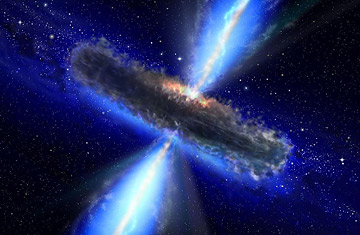

This artist's concept illustrates a quasar, or feeding black hole, where astronomers discovered huge amounts of water vapor

We don't think of the universe as a terribly wet place, but in fact there's water out in space pretty much everywhere you look. A few billion years ago, Mars was awash in the stuff, with rivers scouring twisted channels en route to ancient seas. The solar system from Jupiter outward would be an interplanetary water park if most of the H2O out there weren't frozen. Saturn's rings are made mostly of trillions of chunks of ice. The comets are mostly ice. So is Pluto. Jupiter's moon Europa has a thick shell of ice surrounding a salty ocean, kept warm by the little world's internal heat. Saturn's moon Eceladus spews subsurface water into space in titanic geysers that form a ring of vapor that surrounds Saturn. Uranus and Neptune are known to planetary scientists simply as "ice giants."

And it doesn't stop in our solar system. Water — solid, liquid or vaporous — has been turning up for years, all over the cosmos. So it takes a pretty impressive discovery to put space water in the headlines. But impressive may be an understatement for what two international teams of astronomers have turned up. Peering out to the very edges of the visible universe, both groups have detected a cloud of water vapor, weighing in at a mind-bending 140 trillion times the mass of the world's oceans, swirling around a giant black hole 20 billion times the mass of the sun.

To be precise, the water vapor is mixed with dust and other gases, including carbon monoxide, forming a cloud hundreds of light-years across. (The star closest to Earth, Proxima Centauri, is less than four light-years away.) The cloud is so enormous that while it's incredibly massive, it's also vanishingly sparse: the thinnest morning fog is hundreds of trillions of times as dense.

Most surprising of all, perhaps, is that finding such an immense reservoir of water lurking in the cosmos just 1.6 billion years or so after the Big Bang makes perfect sense. Hydrogen has always been the most common element in the universe. Oxygen is less common, but there's still plenty of it, and the two love to combine whenever they get the chance. And in fact, earlier observations had turned up water from only about a billion years later in the life of the cosmos. Earthly astronomers have previously used water vapor swirling around a black hole to try to understand the mysterious dark energy that pervades the cosmos.

The scientists are doing something similar with this new discovery — studying the water to infer what's going on in the black hole. They already know it's not just a black hole but one of a special subclass known as quasars. The body's immense gravity is sucking in gases at a prolific rate, squeezing and heating them until they blaze with a light that can be seen across the universe. Without seeing the water vapor, however, the scientists wouldn't know how much gas lies outside the superheated region and thus how much potential the black hole has to grow. (The answer: It could in theory swell from 20 billion times the mass of our sun to 120 billion times.)

For another class of astronomers, meanwhile, water in the universe has a different significance entirely. As far as anyone knows, water is a basic requirement for the emergence of life. For biology to have arisen on other planets, either inside the solar system or outside it, the fact that there's plenty of the stuff everywhere you look is reassurance that life may be very common too. Much of the water in the universe takes the form of ice, lots as water vapor. But it took only a relatively teeny amount in liquid form to nurture life on Earth — and there could easily be plenty of other places in the Milky Way where the very same thing is going on.