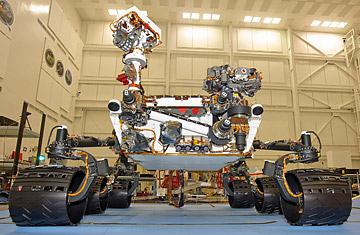

The Mars rover Curiosity, photographed at its testing facility Jet Propulsion Labs in Pasadena, California

Like pretty much every other agency in the government, NASA is likely to be hurting for money over the next few years. The end of the Space Shuttle program, which comes with Atlantis' final flight next month, will free up some cash. But at best, NASA's budget will be flat in 2012, and given the mood in Congress, "at best" isn't something to count on. And thanks to the cost overruns plaguing the yet-to-be-launched James Webb Space Telescope, the agency's science programs are especially vulnerable to cuts.

But that's down the road. For now, things are positively hopping at the Kennedy Space Center. Last week, a brand-new Mars rover, named Curiosity, arrived at Cape Canaveral to be prepared for launch this coming November. But long before that — as early as August 5, if conditions are right — a new probe called Juno will be on its way to Jupiter, followed by the GRAIL mission in September, designed to study the Moon's gravity field in unprecedented detail.

Of the three, Curiosity is sure to make the biggest public splash. Ever since Sojourner, NASA's first Mars rover, transfixed the world as it rolled around the Red Planet during the July 4th holiday in 1997, people have gone slightly mad over these adorable, self-propelled explorers — and after Spirit and Opportunity followed in 2004, the word "plucky" became a space cliche.

All three rovers did spectacular science as well, studying the mineralogy and topography of Mars in astonishing detail, and establishing beyond a doubt that water once flowed and pooled on the planet's surface. The six-wheeled Curiosity will be about the size of a small car (think a Mini Cooper with many millions of dollars of instruments attached) compared to the golf cart-sized Spirit and Opportunity and the microwave oven-sized Sojourner. One thing Curiousity's bulk will buy it is range — far greater than that of the other rovers, partly thanks to a nuclear power source in place of solar panels. That also means that the rover won't have to slow down during the relatively dim Martian winter or worry about dust cutting down on the panels' efficiency at any time of year.

Like its smaller predecessors, Curiosity won't be just a passive observer. It's a rolling laboratory, armed with a laser that can vaporize bits of rock for analysis; a high-resolution camera that can study rocks and even bits of frost at microscopic scales; and a "sniffer" to sample the atmosphere. The ultimate goal: find out if Mars might once have harbored life — or even might harbor it today. Organic molecules embedded in rocks or soil could suggest the former. And if Curiosity's sniffer detects methane gas, it could even imply the latter, since methane can be a byproduct of living subsurface bacteria.

Those answers should start to come in August, 2012, when Curiosity starts rolling. For the Juno mission, things will take a little longer. Though it will launch this summer, the probe won't reach Jupiter until July of 2016. But once it gets there and settles into orbit, Juno will begin an intensive study of the structure and composition of the Solar System' biggest planet. Despite flybys by the Pioneer and Voyager spacecraft, and the long mission of the Galileo orbiter — which sent a probe plunging into Jupiter's dense, roiling atmosphere — planetary scientists still don't know a lot about how Jupiter was formed.

The leading theory suggests that it started out as a rocky planet, maybe 10 times as massive as Earth, but then vacuumed in so much hydrogen and other gases that its solid center was drowned in a chokingly thick atmosphere. But it's also possible that Jupiter formed directly from a collapsing gas cloud, with no underlying planet to do the vacuuming.

Juno could answer that question. Its suite of detectors designed to measure the planet's gravitational field in detail will be able to deduce Jupiter's underlying structure. At the same time, the ship's microwave detector will be able to peer down into the atmosphere to look for the telltale signatures of water and ammonia among other substances. Jupiter's gravity is so powerful that whatever entered that atmosphere during the formation process more than 4 billion years ago has never escaped — making the planet a virtual time capsule whose composition mirrors that of the swirling nebula from which the planets originally formed. (Compare this to, say, Mars, which once had an atmosphere but lost nearly all of it, in part because of the tenuous hold its low gravity had on the gas that surrounded the planet.)

In all, Juno carries 11 different instruments that will also measure charged particles, infrared and ultraviolet light emissions, auroral displays (the Jovian equivalent of Northern Lights) and more. And of course, there's a camera — JunoCam — that will supply spectacular images, including views of Jupiter's poles that have never been seen before.

Finally, there's the GRAIL (Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory) mission, which will reach the Moon four months or so after its October launch (that's a lot slower than the three days it took the Apollo astronauts to get there, but GRAIL is trying to minimize fuel consumption). The probe is actually a pair of orbiters that will orbit in tandem but never touch. The gap between them will change as the ships pass over regions of higher and lower mass, providing clues to the density of the subsurface moon. Eventually, the twin spacecraft will make a highly detailed map of the Moon's gravity field, which will give planetary scientists even deeper clues about the geology of our satellite's interior (in many ways, it's much like what Juno's gravity experiment will do at Jupiter).

It's unlikely that GRAIL will ever be called "plucky," and while a better understanding of the Moon is always a good thing, it won't add to our knowledge the way Juno's exploration of Jupiter and Curiousity's perambulations over the Martian terrain will. Still, it's good news that NASA continues to explore the Solar System in such a wide variety of ways (the Messenger spacecraft, please note, is still sending back a bounty of information about Mercury, while the New Horizons mission is en route to a 2015 encounter with Pluto and Cassini is still circling Saturn). Money may get tighter from here on out, but if these missions are as successful as their designers expect, the agency might feel some pressure to keep coming up with new ones — and get the funding it needs to deliver.