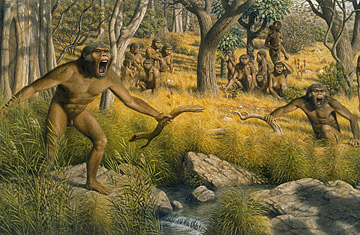

Painting depicting Australopithecus robustus defending territory.

A series of slightly disturbing videos have been making the rounds, showing a gorilla named Ambam walking upright. Gorillas and chimps can walk on two legs, but only for short stretches, and with a kind of bent-over posture. This one, who lives at a wild animal park in Kent, England, stands fully erect. Ambam's odd posture may be learned simply from observing and copying his keepers, but no matter the reason he can do what he does, a gorilla that walks like a human is eerie to watch.

Yet at some point in our evolutionary history, our ancestors may have had a lot in common with Ambam. Walking upright happened before we developed the big brains that made us fully human — that much was made clear back in 1974 with the discovery in Ethiopia of 3.2-million-year-old Lucy (formally know as Australopithecus afarensis), who walked on two legs but had a relatively tiny skull and long, apelike arms. Indeed, paleo-anthropologists are convinced that two-legged walking is what eventually led to bigger brains, as opposed to things working the other way around.

Exactly which of our ancestors started walking in a human rather than apelike fashion has long been a matter of debate. Based on the remarkably rich collection of bones Lucy left behind, plus some fossilized footprints from about the same period in about the same region, she has long been the best candidate for that honor. But there's always been at least some uncertainty, because even Lucy's skeletal remains are missing key bones — critically, some from the foot, which could go a long way toward settling the matter. And those bones haven't been found among the scores of other A. afarensis found over the intervening years, either.

That evidence is missing no more. In a paper just published in Science, a team that includes Lucy's original discoverer, Donald Johanson, now at the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, is announcing they've found one of these bones — not from Lucy herself, but from a member of her species. It's the fourth metatarsal, one of the long bones that connects the toes to the ankles — and it very strongly suggests, say the discoverers, that Lucy and her kin walked in a modern way.

"It's a really crucial piece of information," says lead author Carol Ward, of the University of Missouri in Columbia. "It lays to rest the idea that Lucy walked with an intermediate, shuffling gait. She would have walked like us."

What makes the bone so informative is its shape. The feet of apes are more like hands — pretty much flat when splayed on a flat surface, but also flexible, for grasping and climbing. Human feet, by contrast, aren't very flexible at all. Instead, they're firmly arched, not only from front to back but from side to side. The arching makes our feet natural shock-absorbers — crucial for animals that spend so much time with their weight on just two limbs. The stiffness lets us push off firmly to take the next step.

The bone that Ward, Johanson and their co-author Bill Kimbel (also of the Institute of Human Origins) describe is clearly arched from front to back. Beyond that, says Ward, "when you look at the ends, the back part is angled up, and the bone itself is twisted on its long axis" — evidence of a side-to-side arch as well. "The bone is also very stiff and strong," she says. The structure of the foot not only tells researchers that Lucy and her cousins walked like us, but also that they'd lost the ability to climb trees easily, since prehensile feet — those that can grasp like hands — are critical to good climbing. "A. afaraensis," says Ward, "was committed to life on the ground."

That would have given our ancestor a distinct advantage over other hominids. At that time in Earth's history, the global climate was cooling off, and the lush forests of eastern Africa were changing into a mixed landscape of trees and grasslands in which tree-climbing would have been less useful than walking. A. afarensis also had very strong jaws and teeth, so they could eat a wider variety of foods. "The combination opened up opportunities," says Ward, and Lucy's species had the physical traits that let them take maximum advantage.

Lucy's role as a transitional creature between the more apelike and the more human of our ancestors hasn't seriously been in doubt. But with this new evidence, it's become clear that her stride belongs on the human end of that spectrum.