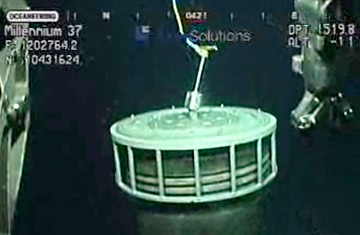

Work continues at the site of the BP Macondo well in the Gulf of Mexico in this frame grab from a BP live video feed September 3, 2010.

Retired Coast Guard Admiral Thad Allen doesn't like to give deadlines for operations on BP's blown Macondo well anymore—and you can't really blame him. Almost every estimate Allen has given on how long it will take to finally kill BP's well has proven overly optimistic. The final bottom kill — which was supposed to be completed by mid-August—has dragged on and on, as BP and its government counterparts have struggled to deal with one unexpected obstacle after another. Those problems haven't led to any additional oil leaking into the Gulf—the well has been effectively capped since mid-July, and Allen declared the threat over when a new blowout preventer was installed recently—but the delays have made the oil spill endgame almost as long as everything that came before it. "This remains a work in progress," Allen told reporters on Sept. 9. "I'm giving you what we have as we've got it."

The main problem remains the same: the engineers are concerned about the condition of the annulus, or outer casing, of the original well, which may have been partially filled by cement during the static kill that was performed way back in early August. The worry is that pumping drilling mud and concrete through the relief well into the bottom of the original well, which will finally and completely kill the spill, might put too much pressure on the annulus and cause further damage and instability. For the past few weeks BP, at the request of Washington scientists, has been working to ascertain the condition of the annulus before the company can go ahead with the relief well. The fact that they haven't been able to do that yet, or at least not to Allen's standards, is the reason work on the well, which began in the early spring and continued through summer, is still going on as autumn approaches and football season has begun.

The original plan for initiating the bottom kill had been to pour cement into the top of the well, which would provide additional support in case the bottom kill caused pressure to build on in the casing. But that would have added weeks to the job, potentially pushing the relief well operation into October. It turns out there may be a shortcut, however: on Sept. 9 Allen authorized BP to put a "lockdown sleeve" on top of the Macondo well, to bulwark the casing hanger, a portion of the wellhead assembly that could be damaged if pressure builds during the bottom kill. (I know—bottom kill, annulus, casing hanger, relief well. It'll all be over soon.) The sleeve, capable of handling 1 million lbs. of pressure, can be installed faster. "It does take a significant amount of time out of the schedule," Allen said, though how much time, he doesn't know.

The relief well will be finished—one of these days. The bigger question is what's happening to the millions of barrels of oil that may still lay beneath the surface of the Gulf, in some form or another. There seems to be good news: bacteria have been breaking down the underwater oil, but they've been doing so without sucking massive amounts of oxygen out of the aquatic environment. That was always a worry. As bacteria proliferate, they tend to use up oxygen, potentially creating dead zones that can cause lasting damage to underwater life. However, according to a report released on Sept. 8 by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), oxygen levels in the Gulf never dropped low enough to create dead zones. "Has it hit the sweet spot?" said NOAA senior scientist Steve Murawski. "Yes."

The results of NOAA's initial tests mean that, right now, the application of hundreds of thousands of gallons of chemical dispersants under water looks like it was a good idea. The chemicals broke the oil down before it reached the surface (and eventually the coast), and the bacteria took care of the rest. Of course, environmentalists and many scientists worry that the dispersants themselves could have toxic effects on underwater life—and researchers from the University of Georgia and the University of South Florida have found evidence of thick layers of oil on the sea floor, meaning not all the oil has disappeared. We won't know the results of this unprecedented chemical experiment in the Gulf for a long time, and it is way too early to call this part of the operation a success. As Admiral Allen knows: whatever can go wrong, may go wrong.