Astronomers have uncovered a likely planet around a sun-like star

For almost a decade and a half, astronomers have been finding new planets orbiting distant stars — first a trickle and then, more recently, a flood of alien worlds, with the tally now well above 400, and climbing every day.

The vast majority of these so-called exoplanets have been "seen" only indirectly — by observing the gravitational tug they exert on their parent stars, for example, or in silhouette as they pass between their stars and our telescopes. Ideally, astronomers would love to see the planets themselves, in order to understand what they're made of, how they formed and perhaps whether the most Earth-like of the exoplanets might harbor a primitive form of life.

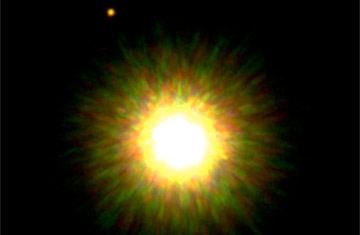

That sort of direct detection is finally starting to happen. In an upcoming paper in the Astrophysical Journal, three observers confirm that they've photographed a planet orbiting a sun-like star known as 1RXS 1609, about 500 light-years, or nearly three quadrillion miles, from Earth, in the constellation Scorpius.

The astronomers first spotted this planet back in 2008, but they weren't sure whether it was really orbiting the star or was just on the same line of sight. Two years later, they've seen the planet and star drift across the sky together, confirming the relationship. And while this one was the first, there may be others lurking in the data.

The chance there's life there, however, is essentially zero: the planet is huge, which means it's almost certain to be made mostly of gas and, therefore, have no surface for life to exist on. It's also farther from its star than any planet ever seen — about 330 times as distant from its star as Earth is from the sun. (Jupiter, in comparison, is only five times farther than Earth from the sun.) That would ordinarily make the giant world far too frigid for living things. In this case, however, it's far too hot. The planet is only 5 million years old, and the lingering heat from its formation keeps it at about 2,700°F. (It's also too young to have evolved life.)

Its searing temperature is in fact the only reason astronomers could see the planet in the first place. It's also why they decided to point the giant Gemini telescope, located atop Hawaii's Mauna Kea, at the Upper Scorpius Association. What sounds vaguely like a British football team is actually a nursery of young stars, and the scientists concentrated on 85 of the Upper Scorpius newborns. "We knew that if they had planets, these would also be young and hot, making them relatively easy to see," says co-author David Lafreniere of the University of Montreal.

Life-harboring planets, in contrast, are likely to be old and cold — like Earth — and so close to the blinding glare of their stars that they are doubly hard to spot. It might only be possible to see them with an advanced telescope in space, or perhaps with the new generation of ground-based instruments that are equipped with coronagraphs, which blot out a star's light, and adaptive-optics systems, which eliminate the shimmering of Earth's atmosphere. These devices should be operating on Gemini's southern twin, Gemini South based in Chile, by next year, and also on the Chile-based European Large Telescope.

While the newly spotted planet doesn't do much for the discovery of alien life, it does hammer home a lesson that astronomers have learned over and over: planets come in a much wider variety and in a bigger range of orbits than anyone imagined. The first new exoplanet, found in 1995, was so close to its star that its "year" was only a few days long. This new planet is so far out that it takes 6,000 years to complete a single orbit — and it couldn't have been found any other way but direct detection.

"As a human being, I can understand the bias in favor of finding planets where life is possible," says co-discoverer Ray Jayawardhana of the University of Toronto. "But aside from that, it's important to see full diversity of what's out there. Direct imaging is revealing an entirely new population of planets that couldn't be detected until now."

Lemonick is the senior science writer for Climate Central.