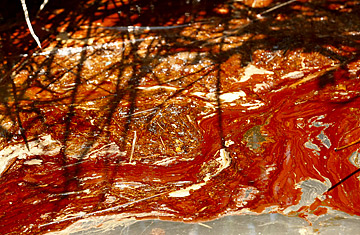

Oil is seen floating on the water in a marsh in Pass a Loutre, La.

Since the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded on April 20 and began spilling an untold amount of crude into the Gulf of Mexico, authorities and Gulf Coast residents alike have worried about what would happen if the oil breached the sensitive marshes of the Mississippi Delta in Louisiana. The state is home to 40% of the coastal wetlands in the continental U.S., and if oil were to reach its sponge-like land, cleaning it up could be impossible. For nearly a month after the spill, fortuitous currents and hundreds of thousands of miles of shoreline boom kept the marshes mostly untouched — though residents knew it might only be a matter of time.

That luck finally appeared to run out on Wednesday. Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal, returning from a boat tour of the state's southern marshes in Plaquemines parish, told reporters the oil had arrived. "We saw some heavy oil stranded in the wetlands," Jindal said at a press conference in the southern town of Venice. "The oil is no longer just a projection or miles from our shore. The oil is here. It is on our shores and in our marsh."

Jindal's report was the most sobering news on a day when the reality of just how serious — and long-lasting — this spill will be began to sink in for policymakers and experts. A day after the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) put nearly a fifth of the Gulf of Mexico off-limits for fishing, the agency reported that an eastern tendril of the massive oil slick had entered the Gulf's Loop Current. Depending on the winds and the current's vagaries, oil could soon be making landfall on the western coast of Florida, or even spiral around the state to hit the sensitive Florida Keys and Atlantic beaches.

And that's just the oil we can see. Independent scientists have raised concerns about massive plumes of oil — miles long — far beneath the surface of the Gulf. (The Horizon is leaking 5,000 ft. down.) The energy giant BP has been using chemical dispersants directly on the spill, under the water — something that's never been done before — and while that may keep the surface slick from growing, oil could instead be spreading below the water. The government is trying to keep track of what might be happening so far out of sight, but a lot of that for now is educated guesswork. "We do not have a comprehensive understanding as yet of where that oil is," Jane Lubchenco, head of NOAA and a marine scientist, told a congressional hearing on Wednesday. "We are devoting all possible resources to understanding where the oil is and what its impact might be."

There is a growing chorus of independent scientists who are questioning why that's taking the government and BP so long. At the beginning of the spill, BP estimated that 5,000 bbl. of oil were leaking every day — a number that was calculated by observing the size of the surface slick. Since then the company has cautioned that the figure could be higher, but it refused to release more than a brief clip of its videos of the underwater leak that might allow independent experts to get a better fix on the rate of flow. BP also refused to allow scientists to send equipment to the seafloor, to get a better sense of how that oil is spreading, while claiming that the spill rate wouldn't affect its response anyway. The government, for its part, deferred to BP — a reminder that while the Coast Guard is supposed to be the final authority on the spill response, this is ultimately BP's show. When asked why greater efforts weren't being made to determine the rate of the leak, federal officials have said they are focusing on closing the well and protecting the shoreline and that the size of the spill doesn't change those priorities.

On Wednesday, frustration broke through, thanks to pressure from Congress. "This may be BP'S footage, but it's America's ocean," said Democratic Congressman Edward Markey. A number of scientists publicly questioned the 5,000 bbl.-a-day figure — independent estimates are 10 to 15 times higher — and called on the government to force BP to allow access to the underwater video footage. "It seems baffling that we don't know how much oil is being spilled," Sylvia Earle, a famed oceanographer, said on Wednesday on Capitol Hill. "It seems baffling that we don't know where the oil is in the water column."

Those protests had an effect: under pressure from Congress, BP decided to allow a streaming video of the spill, which will be accessible on the Web. That should help scientists get a better fix on the sheer size of the problem facing the Gulf States. But there's no doubt that the threat is massive, especially in Louisiana. If oil penetrates the marshy wetlands around the Delta — already badly degraded by recent hurricanes and unchecked development — it could sink deep into the soil and affect the ecosystem there for decades. "The time to act is now," said Jindal.

Louisiana officials are pushing to build artificial sand booms along the state's barrier islands to provide additional protection to the marshes. But that's a temporary fix; the only permanent one is for the blown BP well at last to be closed. The company plans to initiate a "top kill" of the well — essentially clogging it with heavy mud and then cement — sometime this weekend. "If the top kill works, we will demob," said Coast Guard Rear Admiral Mary Landry on Wednesday. "Let's all cross our fingers and say our prayers." Right now, that's about all the residents of the Gulf Coast can do.