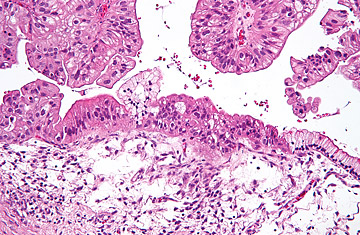

Micrograph of a low malignant mucinous ovarian tumor.

Liz Stegall had no reason to suspect she was at risk for cancer when she decided in 2003 to enroll in a new trial for ovarian-cancer screening at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. She volunteered for the trial primarily to honor the memory of a good friend, who had recently died of the disease. Stegall, 58, of nearby Sugar Land, Tex., said she wanted to contribute to research any way she could, so she offered herself as part of the control group for comparison to the cancer patients in the trial.

What Stegall would soon find out is that she was actually one of those patients. The trial was designed to identify women exactly like her — those who are otherwise healthy but unknowingly harboring the earliest signs of ovarian cancer. In June, researchers from MD Anderson will report the findings of their trial at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting in Chicago, revealing a promising new screening tool that may help catch the early signs of a notoriously difficult cancer to treat.

Ovarian cancer, which kills 14,000 women in the U.S. each year, is relatively rare but has a low rate of survival, largely because most women are not diagnosed until the cancer has progressed to an advanced stage that no longer responds well to treatment. Because the ovaries are embedded deep in the body, tumors emerging in that organ are difficult to detect, either by physical examination or even by more sophisticated molecular methods.

The most widely used test to detect these tumors is a blood test known as CA125, which picks up proteins that are common to ovarian growths. But the blood levels of these proteins also rise in women with more benign conditions, including pregnancy, endometriosis or fibroids. That renders CA125 non-specific as a screening tool, so doctors do not use it routinely in premenopausal women. (The test is used primarily in ovarian-cancer survivors, to keep track of potential recurrences.)

But the physicians at MD Anderson wondered if the test could be made more useful for screening healthy women if it were applied in a more systematic way. In the trial presented at ASCO, they tested women for CA125 proteins annually, and if any changes were detected, the volunteers were tested more frequently — every three months. If the increased screening tests revealed a continued and steady rise in the blood protein levels, the women underwent more detailed ultrasound tests of the pelvic area.

Of the 3,238 women, aged 50 to 74, studied in eight-year trial, about 7% were referred each year for more frequent three-month CA125 screenings; fewer than 1% of these women were considered high risk, and those who fell into that group were assigned to follow up with a gynecologist for further testing. Eight women were eventually found to harbor tumors, and five of them turned out to be malignant. All were caught at an early stage.

Stegall was one of the volunteers whose tumor was detected early by the screen. In her seventh year of the study, the researchers found that her CA125 level had suddenly jumped from a relatively stable 15 U/ml to 70 U/ml. (In most women, levels below 35 U/ml are considered normal.) That was enough to warrant a pelvic ultrasound and exploratory surgery, which revealed a malignant tumor. Fortunately for Stegall, her cancer was confined to a single ovary, and had not yet spread to the surrounding lymph nodes.

Stegall underwent a full hysterectomy and chemotherapy, but she is convinced that the CA125 screen saved her life. "I believe that God and my friend had a lot to do with this," she says. "I would not have been diagnosed at the stage I was, which is the stage at which something could be done."

Dr. Karen Lu, professor of gynecologic oncology at MD Anderson, who led the study, is hoping to hear more stories like Stegall's. "There is clearly an unmet need," she says of the 70% of ovarian cancer cases that are not diagnosed until advanced stages. "I call it the Holy Grail if we could find an effective screening method for ovarian cancer so we can decrease mortality from the disease."

For years, Lu and others have painstakingly attempted to pick out biological markers that could potentially identify ovarian tumors, but not other body tissues. One goal is to pinpoint a panel of genes that code for proteins specific to ovarian cancer — similar to the suite of breast-cancer genes used in the popular Oncotype Dx test for that disease. But year after year, Lu says, they turned up empty. Nothing appeared to come close to the ability of CA125 to predict ovarian cancer.

Yet the CA125 test's specificity for ovarian cancer was a problem, and its sensitivity to it wasn't impressive either: about half the time, in women with early stage cancer, CA125 levels do not creep up in response to the disease. But Lu's team has shown that more vigilant monitoring of CA125 levels can enhance the test's ability to pick up early tumors. "This potentially could become the mammography of ovarian cancer," says Dr. Douglas Blayney, medical director of the comprehensive cancer center at University of Michigan and current president of ASCO.

Lu agrees, but with some caveats. While she is "cautiously optimistic" about her results, she isn't quite ready to begin recommending her testing scheme to other cancer doctors. We still need ultimate confirmation of CA125's predictive ability, she says: a study that tracks women for longer periods of time and documents that CA125-based screening and treatment actually lead to a lower risk of dying from ovarian cancer. "Everyone in the community agrees that if we could find effective methods for early detection, it would really make a huge impact," she says.

Stegall is living proof of that. "I hope that they do find an early detection test because it would have obviously helped [my friend]," she says. "When I volunteered, I didn't think about what it would do for me, but I hope people can learn from me."