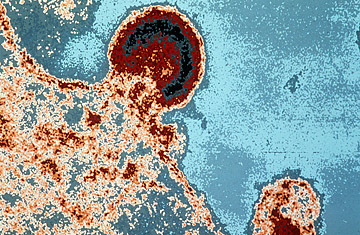

HIV burgeoning on a lymphocyte

Correction Appended: Oct. 23, 2009

Is the AIDS-vaccine syringe half full — or virtually empty? That's the question researchers continue to contemplate following the release on Tuesday of the full trial data of a vaccine tested against HIV infection in Thailand.

The complete, published study results, which include three analyses of the data, suggest that the experimental vaccine may be far less effective than the authors had originally indicated. The vaccine appears to have been slightly more protective among low- or average-HIV-risk participants than among high-risk individuals, like sex workers or intravenous drug users, and its effect appears to wane after the first year.

Nonetheless, many AIDS experts applauded the findings as a crucial starting point for further research. Some say that as slight as it was, the vaccine benefit discovered in the trial may eventually help scientists develop a workable AIDS vaccine — a goal that has eluded them for more than two decades. "Having this signal — even if it's weak and even if we're debating whether it's a real signal or not — is a source of great hope," said Nicole Frahm, an HIV specialist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, while attending the annual AIDS vaccine conference in Paris this week. "Up until now, we've had nothing. This holds the promise of a start."

Detailed simultaneously on Tuesday at the Paris meeting and in a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, the U.S. government–sponsored trial (both the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the U.S. Army provided funding) involved about 16,400 Thai volunteers. Half were given six injections comprising two AIDS vaccines, neither of which had proved effective in previous studies; the other half of the study group was given a placebo.

Overall, the study found that the two-vaccine approach was 31% effective in preventing HIV infection: 51 of the roughly 8,200 people who had been inoculated eventually acquired HIV, compared with 74 people in the placebo group. The analysis that resulted in the 31% figure, however, included study participants who became infected with HIV before the trial concluded and did not complete the entire vaccination schedule; it also factored out participants who were discovered to have been HIV-positive before the trial began. At a press conference at the Paris meeting, Dr. Nelson L. Michael, a virologist with the U.S. Military HIV Research Program, which helped run the $105 million trial, defended that statistical analysis, the "modified intent-to-treat, as the gold standard."

Perhaps, but the release of the trial's full data has not quelled the early criticism that bubbled up around it. Some researchers contend that the second and third analyses of the data — including the "per protocol" analysis, which included only the 12,450 volunteers who received all six vaccine or placebo injections and completed the trial and the "intent to treat" analysis, which included everyone except the previously HIV-infected participants — show that the results are not statistically significant. Both analyses found the vaccine to be just 26% effective — that figure is empirically low, but further, the analyses relegate the finding to statistical insignificance, meaning the results feasibly could have been due to pure chance.

Still, after more than 25 years of virtually futile AIDS-vaccine research, the investigators involved in the Thai trial believe that their findings, while admittedly "modest," offer unprecedented leads to follow. "To quote from our recent history, this is a 'Yes we can' moment," Michael says. "It is not a public health breakthrough, [and] there is not a vaccine around the corner. But the door has finally been cracked open."

Alan Bernstein, executive director of the Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise, suggests that the debate over which analysis of the data matters most — as well as the rather clumsy manner in which the study was presented to the public — is secondary to what the research brings to the battle against HIV. "Let's not get hung up on tangential concerns, and stay focused on everyone's main priority: working our way toward getting a vaccine," Bernstein says. "This trial isn't the big bang. It isn't perfect, and [it] has only provided points of information that must be examined, pursued and — yes — hotly debated. But that's what science is about, and we've got more now to go on than we did before."

Despite the guarded optimism of researchers, AIDS activists in the U.S. and Europe resent what they refer to as the "hype" surrounding the trial's results, which they think continues to raise questions — unnecessarily — about its significance. But specialists like Frahm say that was bound to happen. Against the relentless silence in the field of AIDS-vaccine research, even the tiniest signal from a lone Thai trial can sound like a fog horn.

The original version of this article stated that the two older vaccines used in the new experimental AIDS vaccine were proven ineffective in previous trials. In fact, only one was proven ineffective, while clinical testing of the other vaccine was abandoned before reaching Phase III trials for efficacy.