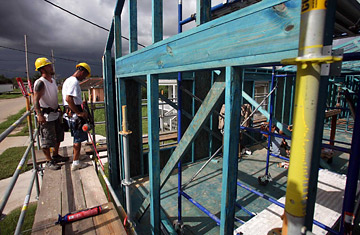

A house under construction in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans in the Make It Right program is designed to be extremely eco-friendly

After Hurricane Katrina flattened New Orleans exactly four years ago, on Aug. 29, 2005, the city emerged as an inadvertent symbol of global warming, the first American victim of climate change. More than 200,000 homes were destroyed during the Category 5 hurricane. But in the years since, the Crescent City has quietly embraced a new and unexpected role as a laboratory for green building. Sustainable-development groups like the international nonprofit Global Green as well as earth-friendly celebrities like Brad Pitt descended on New Orleans, determined not just to build the city back but to build it back green. "It's going to come back," says Matt Petersen, the president of Global Green USA. "But we want to build it better than it was before."

No organization is doing more to green New Orleans than Global Green USA, the American arm of the international environmental organization that was founded by former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. That begins with the Holy Cross project, an entire sustainable village being built in the city's flood-damaged Lower Ninth Ward with the help of Home Depot's corporate foundation. Eventually the village will include five sustainable homes along with an 18-unit green apartment building and a community center. Three homes have been completed so far, including one that is serving as a de facto visitors center. The point of the project is not just to create greener homes for New Orleans' returning residents but also to provide training for the local building community in green standards. "That's one of the ways to make this kind of building more common and more affordable," says Petersen.

That's the motivation behind Global Green's sustainable-schools program, which will both retrofit existing schools to make them more energy-efficient and build entirely new classrooms from the ground up. The new schools will have solar panels, wetland habitats (which can act as a buffer for future storms) and rainwater cisterns. At Gentilly Terrace Elementary School, which is getting an energy overhaul, power bills should fall some $22,000 a year. In a city that is struggling to get back on its feet, those energy savings make a difference — as does the fact that some research has shown that students actually learn better in greener schools. (It's not exactly clear why that's the case — one possibility is that absenteeism and sick days both decrease when the indoor environment is healthier.)

Beyond model projects like the ones Global Green is implementing, there are broader policy-based actions that seek to green New Orleans from the top down. The city is receiving millions in federal stimulus funds, some of which will be going toward initiatives that will re-establish a citywide recycling program and improve mass transit. About $1.1 million is being slated to help green five of the city's libraries, and more will pay for the installation of solar-powered, ultra-efficient LED streetlights. The Department of Energy — with funds matched by Global Green — is underwriting new solar-power projects in New Orleans as well, hoping to expand the tiny slice of the city's electricity that comes from renewable sources. "The hope is that you can help create green jobs for the city in this way as well," says Petersen. "There can be a silver lining to all of this — the creation of a more robust and vibrant community and economy."

Of course, the work of greening New Orleans has been as complex and intermittent as other parts of the reconstruction process, with delays and bureaucratic obstacles. And there's a legitimate question here: Given the increased risk of hurricanes and rising oceans in a warmer future, should a city that exists under sea level be built back at all? Green or not, will New Orleans ever be safe from global warming?

The truth is, none of us will be safe from global warming unless we can change the way we build and the way we use energy — and New Orleans just happens to provide an excellent opportunity to try that in an urban environment that needs to be rebuilt from the ground up. Nor will it be the last major city to be menaced by rising seas — from New York to London to Shanghai, most of our major metropolises are built next to an ocean, and it's only a matter of time before the next superstorm hits. If we can build back New Orleans in a way that is both sustainable and resilient, capable of surviving another Katrina, we all might be better prepared for the hot and unstable days to come.