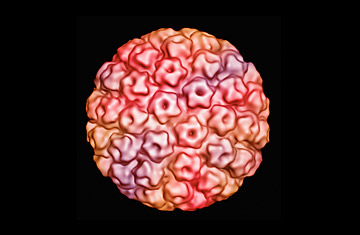

Cryo-electron micrograph of human papilloma virus

With the right test, a single round of screening can decrease the risk of death from cervical cancer by more than 50%, according to research published in the current issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

The large, longitudinal study, conducted in nearly 500 villages in the rural Osmanabad district of central India, analyzed the effectiveness of three methods of screening, including the standard pap smear and the newer test for human papillomavirus, or HPV, whose sexually transmitted high-risk strains are known to cause cervical cancer. (Read "Cancer and Insurance: Who Do You Call?")

More broadly, researchers hope their findings will help determine how best to implement health outreach programs in developing communities — a crucial step toward preventing cancer deaths, which are increasing worldwide.

"In developing countries, screening is not that common," says Dr. Rengaswamy Sankaranarayanan, lead author of the study and head of the screening group at the International Agency for Research on Cancer. There are small-scale cancer screening efforts underway primarily in urban areas throughout Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, but they serve only a tiny slice of the population who would benefit, according to Sankaranarayanan. For example, "in India, less than one million pap smears are taken each year," he says, a fraction of the more than 200 million women who are at risk for developing cervical cancer.

Sankaranarayanan's study involved more than 130,000 women, ages 30 to 59, who were randomly divided into three test groups and a control group. Women in the test groups were screened using one of three tests: a pap smear, an HPV test or a visual inspection of the cervix after application of acetic acid (VIA), a component of vinegar that causes precancerous lesions to turn white. Among the study participants, only eight had ever undergone cervical cancer screening before. Women in the control group were informed about the causes and dangers of cervical cancer and instructed where they could go for testing, but were not given specific appointments; only 6% of those women followed through with screenings.

"One of the major barriers for screening is that you need to go to a screening center, you have to wait, you have to go back," says Sankaranarayanan. "Many of these women are poor women who have to go and work in the field every day." And many do not understand that cervical cancer can be deadly. "There are a lot of false assumptions," he says. "People aren't aware of the severity of the disease."

Of the women in the three experimental groups, who were given pre-scheduled screening appointments, nearly 80% showed up. Those who had a positive screen result or visual evidence of cervical dysplasia (abnormal cells on the cervix) were given follow-up treatment, including further testing, cryotherapy (the freezing and removal of abnormal cells) and, in cases of more serious cancer, surgery and radiation. (Read "Despite US Drop, Cancer Rates Grow Worldwide.")

Over the course of the eight-year study — women were tracked from 1999 to 2007 — researchers found that the HPV screen routed out more cancer and prevented more deaths than either of the other screening tests, and did so with the fewest false negatives. Among some 30,000 women screened for HPV, only eight patients who received negative results went on to develop cervical cancer. In the pap smear group, 22 women, or nearly three times as many as in the HPV group, who had negative results later developed cancer. In the VIA group, there were even more false negatives, with 25 women. In addition, in the HPV and pap smear groups, 60% of cancers were detected early, in stage I of development, compared with 42% in the VIA group.

"HPV appears to be a better test for screening," Sankaranarayanan says, reaffirming previous studies that have established a strong correlation between positive tests for HPV and development of cancerous lesions.

But HPV is a tricky virus to manage. Sankaranarayanan points out that, first, it is exceedingly common; there are some 100 different strains of HPV, of which 30 or 40 affect the vast majority of sexually active people during the course of their lifetimes. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that as many as 80% of sexually active women (and 50% of all men and women) will be infected with HPV at some point. Second, the body most often clears the HPV virus on its own, without ever causing cancer or other symptoms (some strains of HPV also cause genital warts). "More than 80% of the infections will clear within two years of acquiring," he says, underscoring the accepted recommendation by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that HPV tests not be used as a cervical-cancer screening tool in younger women, but only in women ages 30 and older. Infections are more likely to be persistent in this age group, which puts them at greater risk for cervical cancer. For younger women and girls, between the ages of 11 and 26, health authorities in the U.S. and several European countries recommend the HPV vaccine to prevent infection.

From a practical standpoint, limiting HPV testing to women over 30 can also reduce unnecessary costs in treating patients in whom the infection would have resolved itself, a particularly important factor to consider when attempting to get cervical cancer prevention programs off the ground in the developing world and among lower-income women, Sankaranarayanan says. Indeed, the current standard in HPV tests, the Hybrid Capture II, which was used for this study, is already too costly for wide-scale application, running as much as $30 per test. Realistically, in order to be used on a grand scale, tests would have to cost about $1 each, Sankaranarayanan estimates.

In that respect, there may be hope on the horizon. A Chinese study, funded in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (as was the current study) and published in 2008, reported that a new HPV test, called careHPV, is easier to use, produces results faster and is just as effective as the Hybrid Capture II. Researchers say that when careHPV becomes available — Sankaranarayanan anticipates it will be on the market within two years — it will cost a fraction of the price of the Hybrid Capture II.

In the meantime, he says we need to educate people about cervical cancer and the virus that causes it, particularly in the developing world. Combating the disease begins with simple steps, Sankaranarayanan says: "Taking away the stigma of HPV infection and specifically targeting these deprived groups with the proper education."