Americans are fond of the idea that they can keep from doing "bad" drugs by taking "good" ones instead. The heroin/methadone model has actually been institutionalized: you can go to government-funded clinics to get methadone as "maintenance treatment" for heroin addiction — since both drugs bind to the same brain receptors. Experimental types in the '60s believed that LSD was a wonder drug that could cure alcoholism. The same claim was made during the '80s for a drug that was, at the time, perfectly legal and even used by a few psychotherapists: MDMA, a chemical now better known as ecstasy.

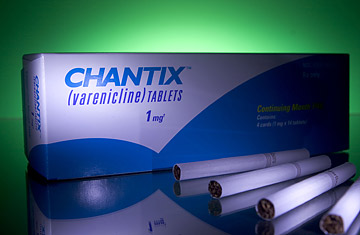

For decades, the holy grail in the search for good drugs to supplant bad ones has been a pill that might replace nicotine, which is powerfully addictive and — especially when delivered through cigarette smoke — incredibly dangerous. And in 2006, the holy grail seemed to have been found. Pfizer released Chantix, a drug the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved in May of that year to help smokers quit. Since then, doctors have written more than 6 million prescriptions for Chantix. It's no magic bullet. Chantix fails with most people who take it; fewer than half of those on the drug actually stop smoking. But going cold turkey works for fewer than one in 10 smokers, so in comparison Chantix is considered a great advance.

Now a new paper in the journal Biological Psychiatry says the drug, which carries the generic name varenicline, has also helped a group of regular drinkers consume less alcohol. So could varenicline be a new anti-addiction panacea?

The new study, which was conducted at Yale, is small but promising. Twenty regular drinkers (defined as those who consume at least one drink per day and, at least once a week, three or more drinks in a single sitting) took varenicline or a placebo daily for a week before showing up for the experiment. None was dependent on alcohol, and none had tested positive for illicit drugs. At around 3 p.m. on the day of the experiment, all were asked to drink a cocktail of their choosing. Afterward, if they wanted, they could have more cocktails. The 10 who had taken varenicline drank an average of just .5 drinks after their first cocktail. By contrast, the 10 who were taking placebos consumed 2.6 drinks. Eight people in the varenicline group declined all further drinks after their first, compared with only three in the control group. (It's worth noting that the varenicline takers also smoked far fewer cigarettes than the placebo group during the 14-hour the experiment. Everyone who participated was a regular smoker.)

But there's a downside. Varenicline reduces cravings by binding to and blocking nicotine receptors in the brain. The drug affects how your brain releases dopamine, the key neurotransmitter that plies the brain's reward pathways and lays down roots of addiction. Typically, your brain gets a shot of dopamine every time you have a drink or — if you're a regular smoker — every time you drag on a cigarette. (Or, for that matter, every time you do anything pleasurable, like win at a craps table or snort a bump of coke or crystal meth.)

But by acting on dopamine receptors, varenicline also may change the way some people experience joy. Last year, the writer Derek de Koff (who was a longtime smoker and also — full disclosure — an acquaintance of mine) wrote a harrowing New York magazine account of his experience with varenicline. He experienced awful hallucinations while taking the drug — he wrote about speaking to a man in a bar who turned out to be a shadow cast by a potted plant. De Koff also became despondent. "I wondered whether [varenicline] was zapping my brain's pleasure-delivery system to such a degree that not only did I find no reward in cigarettes, but I also found no reward in socializing, exercising, writing, or any of my usual self-stimulating tricks," he wrote. De Koff thought about throwing himself in front of a bus or launching his head into his computer.

He isn't alone. Last year, the FDA issued an alert noting that "serious neuropsychiatric symptoms have occurred in patients taking [varenicline] ... These symptoms include changes in behavior, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal ideation, and attempted and completed suicide." The deaths of a musician and a TV executive have been linked to use of the drug.

But varenicline is only the most recent anti-drinking drug to have negative side effects. Some of these side effects are considered to be the treatment itself: disulfirman, also known as Antabuse, which has been used with alcoholics for many years, causes hypotension and vomiting when a person has alcohol. Naltrexone, which blocks opioid receptors in the brain, is another option for chronic drinkers, but it can cause nausea.

Similarly, varenicline is no cure-all. In another new study, this one published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, a team led by Seattle researcher Jennifer McClure found that a group of smokers with a previous history of depression experienced irritability, anxiety and depressive symptoms slightly more frequently while trying to quit with varenicline than smokers with no prior history of depression.

The study did find that among the 1,117 patients who took varenicline, 43% were cigarette-free after three months. But the balance of evidence so far suggests that while trying to quit one drug by taking another may be useful, you don't get something for nothing. Swallowing a pill is better than poisoning your lungs with smoke or pickling your liver with bourbon, but you shouldn't fool yourself into thinking the pill can't harm you.