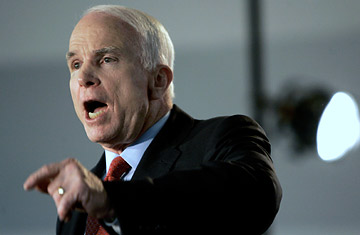

John McCain speaks at Vestas Wind Energy in Portland, Oregon.

Perspective is everything in politics, and after nearly eight years of President George W. Bush's disastrous environmental policy, Attila the Hun would have looked green by comparison. Certainly Senator John McCain falls into that latter category. The presumptive Republican nominee was an advocate for taking action on global warming back when President Bush was still calling for more research into the problem. McCain hasn't been shy about touting his green credentials on the campaign trail — especially now that he has the Republican nomination sewn up and needs to appeal to independents worried about global warming. At the same time, McCain has been wobbly on environmental issues as a legislator — his lifetime score from the League of Conservation Voters is 24%, while Democratic Senators Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton both score 86%. So, when the McCain campaign announced that he would spend much of this week addressing the environment, starting with a speech on climate change Monday afternoon in Portland, Ore., it was worth asking whether this pitch is mostly about politics — or whether McCain is really serious about taking on climate change.

Try a little of both. McCain's speech — where he soberly warned of the catastrophic consequences of climate change and vowed that he would not "shirk the mantle of leadership that the United States bears" — was most remarkable for what it said about the changing politics of global warming. It is difficult to imagine a Republican candidate for President calling for a mandatory cap-and-trade system that would reduce U.S. carbon emissions to 60% below 1990 levels by 2025, as McCain does, or insisting on engagement with rising developing countries like China and India. It's sign that global warming has reached the mainstream, that it will be increasingly difficult to find politicians who claim it's simply a hoax, as Republican Senator James Inhofe once said, or who ignore it, as President Bush has largely done. But when it comes to the nitty-gritty of McCain's policy recommendations on climate change, he doesn't quite make it. McCain might get an A for effort, and his "straight talk on climate change" might win him some independent support — but both Democratic candidates are pushing for tougher action than McCain is. He's greener than Bush, but that doesn't make him the green candidate.

Like Obama and Clinton, McCain is calling for a mandatory cap-and-trade program that would gradually tighten limits on national carbon emissions, with the goal of reducing emissions to 60% below 1990 levels by 2050. (A number of similar bills have already been introduced to Congress, including one by McCain himself and another, by Senator Joseph Lieberman and John Warner, that has made it past the Senate's environment committee.) Like Obama and Clinton, and increasingly most mainstream environmentalists, McCain wants to let the private market do the work of cutting emissions, by effectively putting a price on carbon dioxide and thus incentivizing industry to find a way to use less of it. "What better way to correct past [environmental] errors than to turn the creative energies of the free market in the other direction?" McCain said Tuesday. "In all its power, the profit motive will suddenly begin to shift and point the other way toward cleaner fuels, wiser ways and a healthier planet."

No argument there. But McCain's goals are weaker than those of Obama or Clinton — who call for 80% reductions by 2050, in line with recommendations from the U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — and weaker than the Warner-Lieberman bill, which is seen by many environmentalists as a compromise unequal to the scale of the cuts needed to avert dangerous warming. Though he didn't make this explicit in his speech, under his cap-and-trade plan McCain would initially give away most of the permits to emit carbon to industries, rather than auctioning them off, as Obama and Clinton would. (This means that under McCain's plan, carbon prices are likely to be lower than under the Democrats — and he'll miss out on the revenue created by an auction system, though McCain says that he'll gradually phase out the permit giveaway.) And McCain is, ultimately, a Republican — he said little about the role that government spending could play in advancing alternative energy, or regulating better energy efficiency. His tack is all free market, all the time. Yet global warming is simply too overwhelming a threat to be solved by the invisible hand alone, even if it gets a little nudge.

Most hopefully, McCain was realistic about the need for the U.S. to take the lead internationally on cutting carbon emissions, even without other major industrializing nations. "If the efforts to negotiate an international solution that includes China and India do not succeed, we still have an obligation to act," he said. That was a remarkably un-Bush thing to say — the President has long refused to engage seriously on an international climate change regime unless China and India take on emission-reduction goals too — and indeed, it was McCain's implicit criticism of Bush that most stood out in this speech. "I will not permit eight long years to pass without serious actions on serious challenges," said McCain. His policies may not quite match his words, but McCain showed today that inaction on warming is no longer an option in presidential politics.