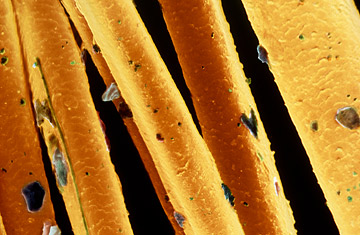

Colored scanning electron micrograph of strands of human hair

She is someone's daughter — but whose? All that's left of the young woman is 26 bones, some hair, a T-shirt and a necklace. This is the crime scene hunters came across one October day in 2000, west of Salt Lake City and not far from Interstate-80. This "Jane Doe" remains unidentified, but with a new hair analysis method, some pieces of this grim puzzle can be snapped into place.

Analysis of hair has always been a good way of telling what's going on in the body that grew it, but now it's being used more creatively than ever by forensic scientists, such as James Ehleringer and Thure Cerling, two University of Utah professors. Ehleringer, a biologist, and Cerling, who studies geology, geophysics and biology, co-founded Isoforensics, Inc. three years ago. Their company uses stable isotope analysis of forensic substances to find slight variations in chemical elements' various isotopes. (Isotopes are forms of the same chemical element with different atomic weights.)

"Hair is a good trap for all those things flowing through the blood system," says Ehleringer. Traces of the food, water and air we breathe show up in our hair (as do drugs and heavy metals). Some 85% of the variation in isotope levels in a person's hair is explained by variations in drinking water isotope levels in areas they spent time. This "isotope signature" from water is not complicated by other beverages because many of them are made using local water.

This is precisely the insight that shed some light on the identity of Jane Doe. Twenty strands of Jane Doe's hair were analyzed using this method discovered by Ehleringer and Cerling. By studying the variation in hydrogen and oxygen isotopes in hair and water in different parts of the United States, they are able to relate it to where a person lives. "From her hair we know that she spent the last two years of her life in the Salt Lake City area and the Intermountain West and that she moved every couple of months," says Salt Lake County Sheriff's Detective Todd Park, who works cold-case homicides.

Using hair and water samples from around the U.S., the scientists produced a color-coded map showing the isotope levels in the water in different parts of the country. Specific cities cannot be pinpointed, but certain states and regions can be. "This analysis can eliminate about 90% of the U.S. as a possibility," says Cerling. "The ability to exclude is just as powerful as the ability to include in forensic science." "It helps me concentrate my efforts in a smaller area," explains Park. "It's like if you lose your car keys, instead of having to look through the entire house, you can focus on just the kitchen."

But not all hair is equally revealing; the longer the hair, the greater extraction of information. Long hair can provide police with a two- to three-year history, whereas short hair may only reveal three to six months. Hair grows about half an inch a month; it also falls out. Every time we take a step, skin cells flake off our body and hair can do so just as randomly, though not as frequently. There are two kinds of hairs on our head: those in the growth stage and those that are not, which are the ones more likely to fall out. The non-growth-stage hair will have a gap in history starting when it stopped growing, which may be anywhere from a few weeks to a few months.

Hair also makes a good forensics tool because it tends to stick around, decomposing at a much slower rate than other parts of the body. A criminal may unknowingly leave behind a strand of hair, a clue for detectives now to follow up on. "A single hair can determine a person's location during the past weeks or even years," says Cerling.

This method can also help in proving or disproving alibis. For example, if a serial killer is roaming the country and claims that he has never been in Akron, Ohio, but you have a history of his hair that places him in that geographic area, it raises some questions. "It's like a credit card transaction that puts you in a place. If you said you were never there, then you have some explaining to do," points out Park.