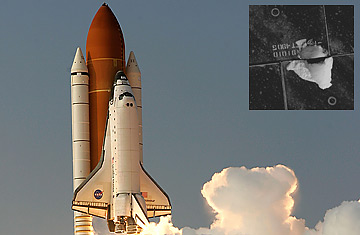

An inset shows the gouge in the wing of the Shuttle Endeavour

Pilots have always had a pretty generous standard for judging what constitutes a safe return home: any landing you can walk away from, they say, is a good one. All the current handwringing about the gouge on the belly of the space shuttle Endeavour notwithstanding, the odds are extremely high that the seven astronauts aboard the ship will indeed walk away when their mission ends 10 days from now. That doesn't mean that there won't be plenty of knotted stomachs in Mission Control and the homes of the crewmembers until then — and with good reason.

Fifty-eight seconds after launch, a fragment of ice or insulating foam once again broke away from the shuttle's external fuel tank and — once again — left a deep divot in the ship's insulating tiles. It was foam damage that killed the shuttle Columbia in February 2003, when superheated gases generated during reentry entered the ship through a breach in the insulation. Ever since then, astronauts have given their spacecraft a close visual inspection upon reaching orbit to look for any troublesome chips. On Sunday, a 3D laser imager attached to Endeavour's robotic arm revealed what could be a nasty one.

Measuring about 3.5 in. long and located near the ship's right wheel well, the breach goes all the way through the inch-thick, heat-resistant ceramic, down to the fabric insulation below. It cuts across at least two tiles and perhaps a third. There is nothing at all good about that kind of break. The wheel well is a particularly vulnerable spot, since damage there can provide easy access to the fragile innards of the ship. It was Columbia's left wheel well that first showed signs of overheating in the lead-up to the fatal accident, as searing plasma leaked into the vessel's interior. What's more, the greater the number of tiles damaged by debris, the greater the jagged area exposed to the force of rentry — something which can, in theory, lead to a catastrophic peeling away of whole stretches of tiles. The comparative severity of the injury to Endeavour is leading NASA to conclude that it was probably denser ice, not comparatively light foam, that is responsible for the damage.

But Endeavour has plenty of things going for it. While the temperature in the vicinity of the wheel well grows blistering during reentry — on the order of 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit — that's a fair bit cooler than the 3,000 degrees reached at the spacecraft's nose and wingtips. Even damaged tiles can usually survive the heating at the aft end of the ship. NASA reports that it caught one bit of good luck in that the breach occurred right over a stretch of the aluminum framework of the ship itself — a bit like damaging a sheet-rock wall directly over one of the wooden beams that holds the wall up, as opposed to the unsupported stretches in between. That indeed is a stroke of good fortune, but less of one than NASA makes it out to be. Since the melting point of aluminum is just 1,220 degrees Fahrenheit, the framework could survive superheating only so long before failing.

NASA plans to announce today whether it will send the astronauts outside to repair the damage — something they could do by attaching a protective plate, dabbing on insulating paint, or squeezing on a layer of epoxy-like insulation. None of the fixes is perfect, though all of them do help — and all of them entail the added danger of an unscheduled spacewalk. (Two astronauts went out on a scheduled spacewalk this morning to replace equipment on the international space station, and two more walks are scheduled for Wednesday and Friday.)

The biggest reason to be optimistic might simply be history. It's true that two shuttles have been lost to disaster in the 26 years of the program, but 117 have made it down just fine. And the large majority of those ships came home with scarred, pitted and missing tiles. Indeed, the early shuttles often shed tiles like dead leaves and landed safely all the same. Endeavour will almost surely do so too. But the anxiety this mission is causing is one more reason that so many NASA employees and astronaut families are simply marking time until shuttles' scheduled retirement in 2010, when the snakebit ships will fly no more.