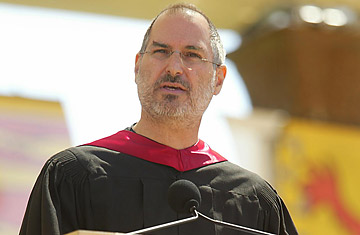

Jobs speaks at the graduation ceremonies at Stanford University on June 12, 2005

(5 of 5)

The iPhone had serious competition, especially from handsets that used Google's Android operating system. But the iPhone ecosystem — phone plus apps, movies and music delivered through Apple services — contributed to Apple's success in a way no other company could match. By 2011, Apple was selling more than 220,000 iPhones a day and, according to one analyst, capturing two-thirds of the industry's profits.

In 2010, Apple followed up the iPhone with the iPad, its first effort in a category — tablet computers — that had existed for two decades without a single hit product. Apple sold 14.8 million iPads in 2010, a number that dwarfed the predictions of Wall Street analysts. (It also flummoxed competitors, who rushed into the market with iPad competitors that were far less appealing, and sometimes much more expensive, than the real thing.) By then, it wasn't surprising that Steve Jobs had surpassed almost everyone's expectations; it would have been more startling if he hadn't.

Apple's business model at this point bore little resemblance to those of other computer makers. The rest of the industry was deeply decentralized: a consumer went to Best Buy to purchase an Acer computer running Microsoft software and then used it with Rhapsody's music service and a SanDisk MP3 player. Tech support was typically outsourced to some nameless firm halfway around the world.

Apple had long ago stopped building its own stuff — one of its contract manufacturers, China's Foxconn, earned its own measure of celebrity — but otherwise, it controlled what Steve Jobs called "the whole widget." It wrote its own software, designed its own hardware and delivered such services as iTunes. It sold Macs, iPods and other products at its own stores, where face-to-face support was available for free at a "genius bar." Once you owned an Apple device, you filled it with movies, music and apps from Apple's online stores. The company even started designing its own processors for the iPhone and iPad. In short, it came as close as it possibly could to fulfilling the Jobs vision down to the last detail.

Jobs remained the difficult, demanding, sometimes unreasonable perfectionist Apple had thought dispensable a dozen years earlier. But the NeXT and Pixar experiences had instilled in him new discipline. He still pushed boundaries but in ways that more consistently worked in Apple's favor. And working with chief operating officer Tim Cook, later to succeed him as CEO, he turned the company into a wildly profitable exemplar of efficiency.

More than any other major Silicon Valley company, Apple kept its secrets secret until it was ready to talk about them; countless articles about the company included the words "A spokesperson for Apple declined to comment." It wasn't able to stomp out all rumors, and in 2010, gadget blog Gizmodo got its hands on an unreleased iPhone 4 that an Apple engineer had left at a beer garden in Silicon Valley. Even if Apple detested such leaks, they became part of its publicity machine.

Minimalism came to typify Jobs' product-launch presentations in San Francisco and at Apple headquarters as much as the products themselves. Jobs 1.0 was known for his bow tie and other foppish affectations. Jobs 2.0 had one uniform — a black mock turtleneck, Levi 501 jeans and New Balance 992 sneakers. With kabuki-like consistency, his keynotes followed a set format: financial update with impressive numbers, one or more demos, pricing information and one more thing. Even the compliments he paid to Apple products ("Pretty cool, huh?") rarely changed much.

He generated hoopla with such apparent effortlessness that many people concluded he was more P.T. Barnum than Thomas Edison. "Depending on whom one talks to," Playboy said, "Jobs is a visionary who changed the world for the better or an opportunist whose marketing skill made for an incredible commercial success." It published those words in the introduction to a 1985 Jobs interview, but they could have been written last week.

Still, even Jobs' detractors tended to think of him and his company as a single entity. Apple was demonstrably full of talented employees in an array of disciplines, but Jobs' reputation for sweeping micromanagement was so legendary that nobody who admired the company and its products wanted to contemplate what it might be like without him. Shareholders were even more jittery about that prospect: a stock-option-backdating scandal that might have destroyed a garden-variety CEO barely dented his reputation.

Increasingly, though, the world was forced to confront the idea of a Jobs-free Apple. In 2004, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and told he had months to live; further investigation showed it was a rare form of the disease that could be controlled. Jobs turned day-to-day control of Apple over to Cook, underwent surgery, recovered and returned to work. During a 2009 medical leave, he received a liver transplant. He went on another medical leave in 2011 that became permanent when he resigned as CEO on Aug. 25, assuming Apple's chairmanship and handing off CEO duties to Cook.

Jobs was so obviously fundamental to Apple's success that many feared the company's amazing run would end the moment he was no longer calling every shot. Instead, Apple prospered during his illnesses and absences. By 2011, the vast majority of its revenues came from products that hadn't existed when Jobs took his first medical leave. He had accomplished one of his most astounding feats: teaching an entire company to think like Steve Jobs.

Always happier praising a new Apple product than talking about his private life, Jobs said little about his struggles with ill health. He did, however, address them briefly in the Stanford commencement speech he gave in 2005. And as commencement speakers are supposed to do, he gave the students — most of whom were about the same age he was when he co-founded Apple — some advice. "Your time is limited, so don't waste it living someone else's life," he said, sounding as if the very thought of living someone else's life infuriated him. "Don't be trapped by dogma, which is living with the results of other people's thinking. Don't let the noise of others' opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary."

Steve Jobs' heart and intuition knew what he wanted out of life — and his ambitions took him, and us, to extraordinary places. It's impossible to imagine what the past few decades of technology, business and, yes, the liberal arts would have been like without him.