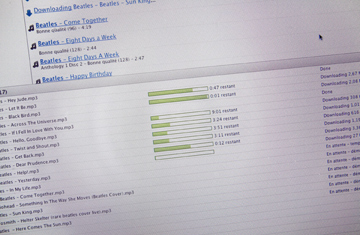

This picture taken in Paris shows a MP3 music file being downloaded through a peer to peer website

When France passed its trail-blazing Internet anti-piracy law in 2009, downloaders decried its harsh penalties — then the toughest in Europe — while lawmakers throughout the continent waited to see whether the French had finally found a way to stop the illicit web sharing of copyrighted music and movies. Two years on, and a poll reveals that France's Internet pirates remain as defiant as ever. All over Europe, legal efforts to battle piracy are proving imperfect and ineffectual — but authorities vow that they will keep pushing to get the legislation right despite the stiff resistance they've provoked.

Six months after the creation of France's High Authority for the Broadcast of Works and Protection of Copyrights on the Internet (Hadopi) — the organization central to the country's anti-piracy law — a Jan. 23 poll indicates that 49% of French Internet users continue to illegally download music and video. Despite the penalties Hadopi can seek for errant Internauts — including depriving offenders of their Internet access while forcing them to continue paying for their subscriptions — the poll indicates that 52% of French web surfers say the advent of the organization hasn't altered their net habits at all.

"You've got millions of people using the Internet in France, and millions downloading copyrighted files, so the chance of little old me being caught by Hadopi is pretty small," says a frequent illegal downloader who asks to be identified only as CBo. "I'm not stopping until I'm caught."

Hadopi officials, however, are finding good news behind the bad. Though the vast majority of file sharing in France was peer-to-peer (P2P) prior to the law's passage, the poll found that P2P use has declined to 42%. Instead, use of direct-download sites like Megaupload and Rapidshare — whose downloaded content can't be detected by outside monitors — has shot to 37%. Similarly, the number of people downloading via captured streamed content — when video or music is saved to a computer's memory as it is played by a remote site -- is on the rise. Authorities take heart in the idea that those shifts at least suggest that the French are more aware of the risks of illegal file-sharing.

"If Hadopi is already moving people to swap more exposed P2P downloading for more secure options, it indicates they're aware it's against the law and carries consequences," says Jacques Bille, a Hadopi magistrate. "Over time, we hope evolving sensibilities — awareness that stealing a copyrighted movie or music file isn't legally different from stealing a book or DVD from a shop — will incite people to give up illegal downloading as wrong."

Bille adds that people may well start taking Hadopi more seriously as its administrative machinery shifts into full gear. The law operates on a three-strikes logic — after a user gets two warnings that their illegal downloading activities have been detected, a third infraction leads to a court-approved penalty. So far, Hadopi has sent out 75,000 warnings since October. "When that mass of first warnings is attained — not to mention second alerts going out — you'll see a lot of people saying, 'Okay, I'm stopping now'," says Bille.

But it will likely take more than a stern warning or two to dissuade hardcore file sharers, or prevent people from using alternatives like identity-masking networks. The fact that Hadopi has so far failed to punish anyone means even the casual downloader views it as harmless. And when France's anti-piracy law and others around Europe do begin to bite, some reprimanded Internauts are expected to mount legal challenges to the new, untested legislation.

That already appears to be the case in the London trial that opened Jan. 25 involving 26 alleged copyright pirates. Under Britain's 2010 Digital Economy Act, anti-piracy companies who represent copyright owners — such as music labels and film studios — can monitor file-exchange sites and identify the IP addresses that have been used to download protected works. The anti-piracy companies can then use the law to force Internet service providers to identify the customers behind those IP addresses so they can be brought to trial. Which is all proving to be complex, contentious, and confusing. Indeed, instead of using the case as motivation to explore the issue of illicit downloading, early debate has focused on the legality of the charges and the ethical credibility of the plaintiffs.

Meanwhile, UK broadband service providers BT and Talk Talk have won a judicial review of the law, challenging the legality of its obliging them to cut off customers and block sites proven to have been involved with illicit downloading. Computer cracks around the globe, meanwhile, continue to work on new techniques to stymie the enforcement of laws aimed at reducing what the entertainment industry claims is perhaps $14 billion in lost film and music revenues annually.

The resistance these laws are facing leads some observers to say that the only effective way to end online piracy is for studios and record companies to stop fighting it and start looking at it as an opportunity. "The old model is dead, and the new one is direct Internet transfer between the studio and individual," says one French expert in the sector. "Studios can either accept that with reduced but still profitable prices, or they can continue ignoring the fact that they aren't the masters of the game anymore — and lose everything to piracy."