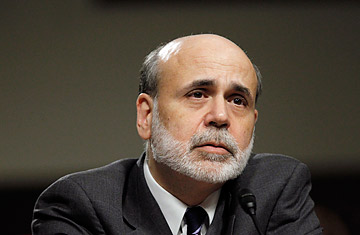

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke

It's not generally a good idea to act like a jerk during an interview. Especially when your bosses are conducting the interview. With the Chairman of the Federal Reserve. Whom they are about to name TIME's Person of the Year.

So I probably should have shut my mouth that December afternoon. I had already spent hours interviewing Ben Bernanke myself. I had plenty of material for a profile. But I wanted to take another shot at a question he had ducked: After blasting trillions of dollars into the economy during the financial crisis and its aftermath, was there anything else the Fed could do to fight unemployment?

He sidestepped it again. So I asked it again. And again. My bosses changed the subject. I changed it back. The transcript gets painful to read: "I'm sitting here in front of my boss, and my boss's boss, and my boss's boss's boss, so I probably shouldn't do this." You can almost hear everyone else nodding vigorously, but I kept hectoring the nice man who rules our world, telling him it kind of sounded like he planned to do nothing: "I guess my question is, Is that what you're saying?"

"The additional steps aren't as obvious or clear as the ones we've already taken," he replied. "It's an enormous problem. There aren't easy solutions."

Then back and forth twice more, until one of my bosses asked: "How are we doing on time?" Even I got that hint.

But I also got Bernanke's hint. Because yes, that's what he was saying with his careful not-quite-answers. He honestly believed that unemployment was the nation's most serious economic problem, but he didn't plan to do anything about it.

And he hasn't. While Bernanke's Fed has resisted calls to step on the monetary brakes to avoid inflation, it has also resisted calls to apply more monetary gas to try to accelerate a tepid recovery. It has kept short-term interest rates as low as they can go — and has signaled that they will stay there "for an extended period" despite protests from inflation hawks — but it has refused to pump any more cash into the sluggish economy despite mounting concerns from doves about deflation and a double-dip recession.

On Tuesday, the Fed finally acknowledged the recovery is losing steam, and approved a modest effort to buy Treasury bonds with the proceeds from maturing mortgage securities. But that's just a complex way to maintain the status quo; it will prevent a slight contraction of the money supply, but it won't expand the money supply.

To dovish progressives like New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, the Fed's passivity in the face of rampant unemployment violates its dual mandate to maximize employment as well as stabilize prices — and is heartless and hypocritical to boot. Bernanke, after all, is one of the intellectual godfathers of the dovish notion that central banks can still step on the gas to promote growth even when interest rates hit zero. As a Princeton scholar, he chastised Japan's central bank for passivity in similar circumstances; he also famously argued that passive, inflation-obsessed central bankers caused the Great Depression. And when the financial implosion brought the world to the brink of another depression, he invented all kinds of new monetary spigots to open, blew up the Fed's balance sheet to an unprecedented $2.3 trillion, and stabilized a broken banking system with cash and creativity. That's why he was Person of the Year.

So if Bernanke understands perfectly well that there's more he can do, why isn't he doing it?

The short answer seems to be that Bernanke fears the potential benefits of more monetary stimulus would be modest and uncertain, while the potential risks would be dramatic and real. He's obviously not a do-nothing chairman — he's done stuff no chairman ever dreamed of — and his upbringing on Main Street in a small Southern town sensitized him to economic suffering. But nine months ago, he clearly believed that doing nothing was his least awful option, and he still seems to feel that way.

Don't forget that Bernanke is already presiding over an era of historically easy money. The traditional way for the Fed to juice the economy is to lower interest rates, but they've essentially been zero since December 2008, with the "extended period" signal to assure markets they're staying there since March 2009. In fact, the most strident criticism of Bernanke has come from inflation hawks who call him Helicopter Ben, who say he's manufacturing Zimbabwe-style hyperinflation and Dutch-tulip-style asset bubbles, who clamor for a tight-money exit strategy to start shrinking the Fed's bloated balance sheet. Even inside the Fed, Bernanke has faced heavy pressure from hawks like Kansas City Federal Reserve bank president Thomas Hoenig, who dissented from Tuesday's decision because he thinks the economy is recovering and it's time for the Fed to take its foot off the gas.