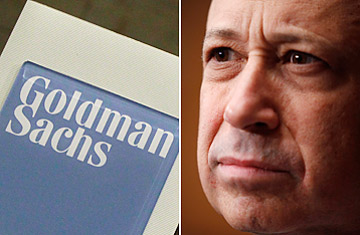

Lloyd Blankfein, CEO of Goldman Sachs

Edward Forst, Goldman Sachs' co-head of investment management, made $44 million two years ago. Never heard of him? That may soon change.

Forst is among a group of top Goldman executives and past employees who are most likely to take over the firm if chief executive officer Lloyd Blankfein resigns. Some others who have a shot in taking over the top slot at Goldman are Gary Cohn, who is Goldman's chief operating officer and is the highest-ranking official after Blankfein at the firm; John S. Weinberg, who runs the firm's investment banking division; Bryon Trott, long known as Warren Buffett's favorite banker; and Suzanne Nora Johnson, a former vice chair of Goldman and the firm's highest-ranking woman until she left Goldman in 2007.

Ever since the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) charged Goldman with securities fraud in mid-April, pressure has been mounting on CEO Blankfein. Investment bankers at Goldman are reportedly unhappy with the direction Blankfein, a former trader, has taken the firm. What's more, in the past few weeks, the firm has come under fire for the fact that conflicts of interest seem rampant. Many believe those conflicts are due in large part to the culture that Blankfein has created at Goldman.

"The firm will always have a taint as long as Blankfein is there," says top Wall Street recruiter Rik Kopelan of the Capstone Partnership. "And he may not have done anything wrong."

Indeed, the price of those conflicts might soon have a number: $650 million. Analyst Brad Hintz at Sanford Bernstein estimates that's what Goldman would have to pay to settle the charges with the SEC. Goldman officials have reportedly told regulators they would be willing to plead guilty to the lesser charge of failing to disclose material facts if the more serious charges of securities fraud were dropped. But a deal might make it ever harder for Blankfein to hold on to his job. The SEC could make Blankfein's stepping down one of the terms of the settlement, or at least force him to give up his dual role as both Goldman's CEO and chairman. Even if the government doesn't push for Blankfein's removal, the settlement could hurt Blankfein's credibility. He said from the beginning that Goldman did nothing wrong. And many will question whether the decision to not settle the charges immediately were worth the hit Goldman has taken to its reputation and business.

For the time being, analysts and observers say it doesn't appear as though Blankfein is going anywhere. At Goldman's recent annual shareholder meeting, he said the negative attention on the firm had put a strain on Goldman's clients. But he said he had no plans to step down as CEO and chairman. Moreover, a shareholder proposal to basically kick Blankfein out of the chairman role was overwhelmingly defeated.

Nonetheless, even if Blankfein doesn't leave Goldman immediately, the pressure on him has put a new spotlight on the executives who might eventually succeed him. Gary Cohn was the odds-on favorite to take over the firm before the SEC lawsuit and other scandals. But Cohn wouldn't offer Goldman much of a break from its recent troubles. He is Blankfein's chief lieutenant and, like Blankfein, comes from Goldman's trading side of the business. Also, Cohn, like Blankfein, is likely to have approved or at least known about the mortgage deal that is at the heart of the SEC case against Goldman. If the firm is looking for a break from the culture that precipitated its reputational troubles, then the board is unlikely to pick Cohn as the company's next CEO.

If Cohn is passed over, a Goldman executive in the running to get the CEO chair could be Ed Forst. A member of the firm's management committee, Forst worked at the firm for 14 years, eventually rising to become Goldman's chief administrative officer, before leaving two years ago to help manage Harvard University's endowment. He returned to Goldman last year as a senior strategic executive. Earlier this year, he was named head of Goldman's investment management unit, which manages $23 billion in assets.

Naming John S. Weinberg Goldman's next CEO would send a strong signal that Goldman is returning to its banking roots. Weinberg is not only the head of Goldman's investment-banking division but also the ultimate legacy candidate for the CEO job. Weinberg is the son of John L. Weinberg, who ran Goldman from 1976 to 1990, and the grandson of Sidney Weinberg, who ran Goldman from 1930 to 1969.

Another banker who could be considered for Goldman's top role is Bryon Trott, who was once considered the heir apparent to former Goldman boss Hank Paulson. Instead, Blankfein got the top job. Trott left Goldman last year to start his own firm. What Trott has going for him is that he has been long known on Wall Street as Buffett's favorite investment banker. At the height of the financial crisis, Buffett invested $5 billion in Goldman. That could make Buffett a major player in any Goldman succession battle, possibly throwing his weight behind Trott.

The problem with Weinberg or Trott is that traditional investment banking makes up a relatively small portion of Goldman's revenue these days. And the board might not be confident in appointing someone who doesn't have a great grasp on the firm's immensely complex trading book and the risks it entails.

But if Goldman's main goal in selecting its next CEO is to soften its make-money-at-all-costs, vampire-squid image and smooth over feathers in Washington, then the board's best choice for top executive could be Suzanne Nora Johnson. Like Weinberg and Trott, Johnson is an investment banker, having run Goldman's health care banking group. But like Cohn and Forst, she held management roles at Goldman outside of investment banking as well. Before leaving the firm in 2007, after 21 years, Johnson ran the firm's research division and was the head of Goldman's Global Markets Institute as well as vice chair on the firm's management committee. Johnson also has contacts in Washington that might be able to repair Goldman's image with politicians and win some much-needed support for the firm. Johnson is on the board of the the Brookings Institution, the prominent liberal Washington think tank. She is also on the board of the Carnegie Institution of Washington and the Council for Excellence in Government. But Johnson does not come without some financial-crisis taint. She is on the board of directors of AIG, and was a director when the insurance firm had to be taken over by the government. Just another reason why Blankfein might stick around a little while longer.