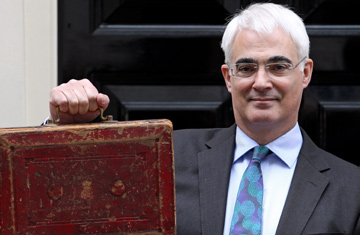

Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling

When you're staring at a $250 billion budget deficit for the year, a fresh tax or two can come in handy. And if unpopular banks are the targets, better still. Few of Britain's voters will quibble with Alistair Darling's call Wednesday, March 24, for a global tax on banks to help recover the billions in public funds doled out during the crisis. "We intend to get all taxpayers' money back," the Chancellor of the Exchequer said during his budget speech to Parliament, his last before a general election expected in May. Charging banks to help do that, Darling added, was an issue on which "more countries agree."

Moves to force lenders to pay up in response to the global financial blowout are gaining momentum. German officials announced plans Monday, March 22, to start taxing banks as a way of squirreling funds for any future bailouts, with details expected to come before the end of the month. U.S. President Barack Obama unveiled proposals in January for a $90 billion bank tax designed to recoup public money used to shore up the nation's lenders. No-nonsense Sweden, meanwhile, has already implemented its own version. But amid this consensus on the need to charge banks, doubts over the merit of the schemes remain.

Having sanctioned some $1.3 trillion in state- and central-bank aid to protect its country's troubled lenders, Britain's government has been mulling a bank tax for months. Prime Minister Gordon Brown's proposal last fall for an international "Tobin tax" — a levy on financial-market transactions ranging from foreign-currency trades to derivatives — received a chilly reception abroad. U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner pooh-poohed it as "not something we're prepared to support." But Darling's call for a global bank tax could yield something closer to the U.S. vision. Such a levy might involve taxing banks' wholesale funding, in line with the Financial Crisis Responsibility Fee proposed by Obama in January.

A crucial feature of any British plan: revenue from the tax would be funneled directly into state coffers — remember that $250 billion deficit — and not into an insurance fund to be tapped in the event of any future catastrophe. Such a pool, the U.K. reckons, could simply encourage banks to behave recklessly, safe in the knowledge they'd be covered for any damage. Germany's proposal is different. Having had to nationalize or buy stakes in a string of beleaguered banks since the crisis began, the German government wants to pass the bill for future bailouts to the banks themselves. Lenders "cannot in the future gamble at the taxpayers' expense," Volker Kauder, parliamentary leader for the governing Christian Democrats, told a national TV network Monday. "Provisions must be made so that they — if things get difficult — pay for things themselves."

The amount such a levy would raise is unclear. If the Germans use the U.S. plan — which calls for a tax of 0.15% on liabilities at about 50 banks and other financial institutions — Germany could raise as much as $12 billion a year. Would that be enough to protect banks in the case of another meltdown? Of course, proper government and regulatory scrutiny can guard against a repeat of the recent crisis. But in the event of a disaster on a similar scale, "you're never going to get a fund big enough to cover all that," says Simon Maughan, a banking analyst at MF Global in London. "The taxpayer is always going to be the backstop. So why not improve the situation today by paying down the fiscal deficit instead of pretending you have an insurance fund?"

The truth is, insuring against future catastrophe is hardly a foolish idea. Putting away at least some of the funds raised in the U.K. or U.S. makes sense. After all, almost all the big lenders who received cash from the U.S. Troubled Asset Relief Program in the current economic downturn have since paid it back. Britain's government, meanwhile, could yet turn a profit by selling stakes in its own partially nationalized lenders.

Convincing every major economy of the virtues of a bank tax, though, remains the biggest challenge. Canadian Finance Minister Jim Flaherty, for instance, rejected a bank tax out of hand earlier this month, favoring instead a wider implementation of some of the tough rules that left his country's banks relatively unscathed by the crisis. But the publication next month of the International Monetary Fund's recommendations on bank taxes — a report commissioned by the G-20 countries last year — might help coax reluctant nations into considering the measure. "Some countries feel they did their homework," says Arturo De Frias, an analyst at Evolution Securities in London. Should there be an agreement on the issue, he says, "I would be very, very surprised."

The trouble is, unilateral measures lack the sting of those enjoying widespread support. Britain's opposition Conservative Party has pledged to introduce a levy of its own should it win the May elections — with or without global support. "It just means there's less you can do if there's not international agreement than if there is," Conservative leader David Cameron said Tuesday. On the back of a one-off tax on bank bonuses and a hike in income tax for its highest paid staff, you can almost hear the financial sector cheer.