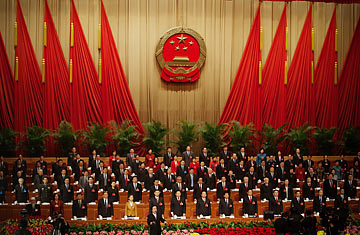

The third session of the 13th Beijing People's Congress

For the past 40 years, Americans have looked at Asia's phenomenal economic growth and asked, What are they doing right, and what are we doing wrong? Today the question rings louder than ever. As Asia surges out of the Great Recession, experts are searching furiously for the secrets of the region's resilience, those nuggets of Eastern wisdom that could rejuvenate a tired and confused U.S. economy.

Don't get your hopes up. Asia can surely provide lessons for the West, but Americans often take the wrong lessons from Asia's growth stories — and we seem to be doing it again now.

That's because many people mistakenly believe that Asia offers a superior political-economic model for meeting the modern world's economic challenges. That perception, however, is based on the incorrect notion that Asia's success is the product of intrusive governments. In the 1980s, when Japan was Asia's rising giant, some said its state-led economic system, in which bureaucrats "picked winners" by targeting industries for special support, was better than the more laissez-faire practices of the West. Today, pundits see China's "state capitalism" as the contender for global dominance. The heavier hand of the Chinese government, this thinking goes, acts as a source of strength in hard times while firmly guiding the nation into the industries of the future. China's vibrancy has even led Americans to question the viability of the very tenets of democracy. "It is intellectually and politically unsettling to realize that, if the West cannot quickly straighten out its systems of government, only politically unreformed states like China will be able to make the decisions that a nation needs to survive in today's high-speed, hi-tech, increasingly globalized world," scholar Orville Schell recently wrote.

Sure, the authoritarian rulers in Beijing can sometimes implement policies more efficiently than the argumentative democrats of the West. That's exactly why Beijing's recession-busting stimulus plan proved more effective than Washington's. With no political debate to get in the way, China's bureaucrats splashed money everywhere to toss up shiny new infrastructure. The slumping economy needs more credit? Well, that's easy — if you own the banks. Just open a spigot and watch the money flow. China's government can also push ahead on important long-term projects with greater speed. While health care reform in the U.S. languishes in Congress, China is building an extensive health care system to cover nearly all of its 1.3 billion people.

But there are few things more annoying than pundits in the democratic U.S., who are firmly protected by the Bill of Rights, waxing poetic about the virtues of dictatorships. What they're forgetting is the frightening downside to China's authoritarian state capitalism, and not just in terms of human rights. China's stimulus program might have produced growth, but it could very well have undermined the health of the banking system. The Chinese economy is riddled with excess capacity, inefficient state enterprises and asset bubbles.

More important, the idea that the state made China rich is simply not true. China only started growing when the overbearing government got out of the way and allowed private enterprise, both Chinese and foreign, to thrive. The same is true in India. Across Asia, in fact, the primary engine of growth has always been the market, not the state. All rapid-growth Asian economies — including China's — succeeded by latching onto the expanding forces of globalization, through free trade and free flows of capital. South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore may have had active bureaucrats, but the true source of their economic growth was exports manufactured by private companies and sold to the consumers of the world. Asia's growth story is more a testament to the dangers of state meddling than its virtues. Just look at Japan, which has been suffering for 20 years from the damage caused by too much bureaucratic interference.