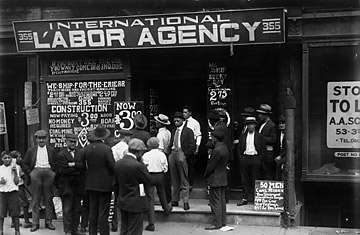

Boys and men wait outside a New York City labor agency in 1912

With stimulus spending doing little to combat an unemployment rate at 10.2% and rising, U.S. leaders are starting to take further action. President Barack Obama is holding a jobs summit Dec. 3, followed by a White House to Main Street Tour to "share ideas for continued recovery." Congressional Democrats, meanwhile, hope to tackle a new jobs bill by the end of the year.

Leaders in the early Republic had it easier. The work of taming a continent provided every American who wanted one with a full-time job and drew settlers from oceans away. Laws like the Homestead Act of 1862 — which granted any man or woman up to 160 acres of public land if they pledged to cultivate it for five years — tapped into the frontier spirit, providing work opportunities for even the most down-and-out Americans. As more and more members of the workforce began laboring in factories in the 19th century, however, society grew more polarized and new technology let businesses squeeze more productivity out of fewer people. By the 1920s, periodic unemployment was common; by 1933, the depths of the Great Depression, it had hit 25%.

Still, President Franklin Roosevelt — who rode into office on a platform of deficit reduction — initially hedged his bets, taking stabs at public-works projects and farm subsidies while also rolling out balanced-budget initiatives. When a British economist visited the White House in 1934 saying deficit spending was the best engine to boost consumer demand and create jobs, Roosevelt balked. (Two years later, the economist — John Maynard Keynes — published that advice in his seminal work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, which revolutionized economic thought by debunking the widely held belief that the market naturally tends toward full employment.)

By 1938, struggling to make a dent in crippling unemployment, Roosevelt had come around to Keynes' advice. It worked: massive New Deal and World War II outlays pushed unemployment down from nearly 15% in 1940 to 1.2% in 1944.

Among the projects that FDR's spending paid for was the Current Population Survey, which has measured unemployment every month since March 1940. The process — which aside from computerization and expansion has not fundamentally changed over the years — centers on interviews with a rotating sampling of 60,000 households. Workers are sorted into three categories: employed, unemployed and not in the labor force. To be counted as unemployed, a worker must have "actively looked for work" in the past month — a definition some analysts say is too narrow to capture the breadth of the economic pain. A more realistic one, they argue, would include discouraged workers who have looked for work within the past year as well as underemployed Americans seeking full-time jobs. Taking these categories into account, the Great Recession has touched 17.5% of Americans' jobs. Talk about an incentive to act.