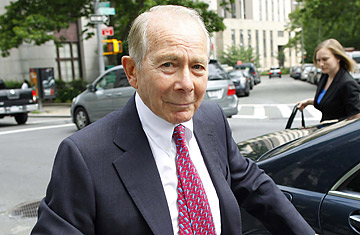

Former AIG CEO Maurice (Hank) Greenberg arrives at federal court in New York on June 16, 2009

That seems to be the multibillion-dollar question in an ongoing court battle that pits Greenberg and his firm Starr International against his former employer AIG. The deeply troubled insurance giant claims Greenberg, through Starr International, improperly gained control of hundreds of millions of shares of AIG stock when he was booted from the company in 2005.

In a trial that started on June 15 in U.S. District Court in New York, AIG contends that the shares as well as over $4 billion in profits that Starr International has reaped from past AIG stock sales were meant to fund a long-standing deferred-compensation program for AIG employees — a program that Greenberg, 84, halted after his acrimonious ouster from AIG amid an accounting scandal.

Starr disputes that, saying the beneficiary of the shares was always a charitable trust and that the company, which has Greenberg as its chairman, can use the stock as it pleases.

Although the outcome of the case will likely hinge on interpretations of legal agreements signed years ago, Greenberg's credibility was on trial on June 16, when the former AIG chief executive took the stand. AIG's lead attorney, Ted Wells, said that Greenberg and other members of Starr's board of directors had broken an agreement not to sell their AIG shares.

Wells told the court that Greenberg in the past has acknowledged in AIG financial filings, speeches and other documents that the stock was meant to be used to benefit employees. "You stated to the participants that the stock was being preserved for future AIG employees," Wells said to Greenberg. "Was it just a coincidence that you said that again and again?" Wells pointed to a "Statement of Commitment" that Greenberg and other Starr directors signed in 1992 pledging that Starr would maintain its investment in AIG despite "unforeseeable" changes in the future.

The most heated part of the testimony came when Wells asked Greenberg whether losing his job justified breaking that oath, implying that he had done so as revenge for his dismissal from AIG after serving as its chief executive for 38 years. "The fact that you lost your job was a big enough act to cause you to breach your fiduciary responsibility?" asked Wells.

"That [selling the AIG stock] was not a breach of our fiduciary responsibility," Greenberg replied. He maintained that Starr — which was long operated as if it were a private subsidiary of AIG — is an independent company with the right to end the compensation plan as well as the right to sell its shares in AIG.

Until 2005, Greenberg was the head of both AIG and Starr, which was one of a number of companies that were the predecessors to the modern AIG. When AIG was formed in the late 1960s and taken public, Starr was given hundreds of millions of shares of the new company. Controlled by AIG executives, Starr was given the shares as a defense against hostile takeovers of the insurance giant. Five years later, Starr set up the disputed long-term compensation plan that for many years rewarded AIG executives from Starr's trove of company stock when the insurer's profits increased.

When Greenberg left AIG in 2005, he took control of Starr and its AIG shares, which at the time totaled 300 million. Starr has since pocketed $4.3 billion from the sale of some of those shares. AIG says those profits belong to the insurance giant, along with the remaining 180 million shares of AIG that Starr still holds, which are worth just over $270 million.

Starr's lawyers argue that the case rests on documents that were drawn up in 1970, around the time AIG became a public company; there appears to be no requirement that Starr use the stock as part of an AIG bonus program forever. In fact, the program had to be renewed every two years.

Still, the outcome will probably not be decided by legal documents alone. Unlike many disputes between two corporations, a portion of this case will be decided by a jury, which will probably put more weight on whether Greenberg is believable.

U.S. District Court Judge Jed Rakoff, who is hearing the case, has said he wants to limit the case to the facts surrounding the relationship between Starr and AIG. Rakoff says he will not allow jurors to hear testimony about the accounting scandal that led to Greenberg's AIG exit or anything related to the insurance company's recent financial troubles, which resulted in a huge government bailout. Excluding the circumstances of Greenberg's exit may make it hard for AIG to prove that he ended Starr's AIG compensation plan because he was angry he had lost his job.

During the trial, Wells, the AIG lawyer, played a video of a speech Greenberg made in 1996 to top AIG executives who had received shares through Starr's compensation plan. Wells asked Greenberg to raise his hand at the point when, during his videotaped explanation of the program, he stated that Starr had the right to cancel the plan and use its AIG shares for other purposes. The speech ran more than six minutes. Greenberg never raised his hand.

Last week, AIG said if it wins the lawsuit, it will use the money to pay back some of the more than $170 billion in government assistance the company has received to keep it afloat amid the financial crisis.