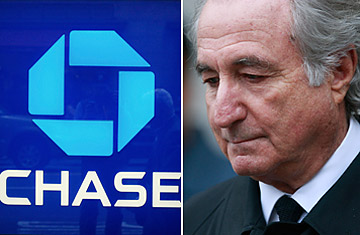

As Bernard Madoff passes time as inmate No. 61727-054 in the Metropolitan Correctional Center in lower Manhattan, questions about his giant scheme continue to dog investigators and the public. Among them is the curious relationship Madoff had with his bank, JPMorgan Chase.

Madoff never used his asset-management money to trade securities, court documents show. Instead, he largely kept it in his Chase account for years. Though Chase bankers never raised a red flag, another arm of Chase did have suspicions about Madoff, and that raises questions. (See pictures of the demise of Bernard Madoff.)

The Chase account, Madoff said in court in mid-March, was used to shuttle money back and forth between his U.S. and London operations, to make it appear he was executing trades in European markets, as he told federal regulators. Madoff made no trades at all with his Chase account, but rather just collected investor monies, wrote checks to investors, and took money for himself. In court, Madoff pleaded guilty to 11 counts of fraud, from wire transfer to money-laundering.

One puzzler for money chasers in Madoff's $65 billion Ponzi is why the multibillion-dollar bank account he kept at Chase never came under suspicion by internal bank compliance systems or managers in charge of Madoff's account. (Watch TIME's video about Madoff's trial.)

When it comes to technology that scans for fraud, today's detection systems are largely focused on identity theft, hackers and account anomalies, according to Don Jackson, director of threat intelligence for Atlanta-based SecureWorks, information-security experts on financial cyberthreat. "The problem with financial-fraud technology is that it's only as good as how it's set up," Jackson says. "If it's set up for a high-volume and multiple-wire-transfers account, then it won't reveal anything strange when there's lots of activity, like Madoff's account. The only way to stop this kind of fraud is for the bank to know its client better and to report things that might be suspicious. It really comes down to human control."

One thing that should have raised suspicions is that the bank's review of its own investments caused it to pull $250 million from a Madoff feeder fund, Fairfield Greenwich, just months before Madoff was arrested. Chase took this action because it became "concerned about the lack of transparency," and its due diligence "raised doubts" about Madoff's operation.

The notion a bank can be concerned about investments with Madoff and then be unconcerned by the same man's vast sums of cash flowing in and out of the same bank has experts and lawyers still shaking their heads. Others see it as a classic breakdown between technology and the human factor.

One lawyer, Howard Kleinhendler, of Wachtel & Masyr LLP, is following the money trail and believes Madoff's Chase account was "suspicious" and should have been shut down the moment the bank pulled its funds from Fairfield Greenwich. Kleinhendler represents a dozen Madoff victims. (Read "Madoff Victims Look for Ways to Recover Their Money.")

Moreover, Kleinhendler believes Chase abruptly pulled its $250 million in August, when, he says, "it learned from Bear Stearns executives that Madoff's investments were phony." JPMorgan Chase acquired Bear Stearns in March 2008. "Bear Stearns had done deals with Madoff. They were on boards together," Kleinhendler says, and therefore, he posits, perhaps executives at Bear knew Madoff's business was fishy and tipped the bank off.

Chase asserts that its withdrawal was normal procedure. The bank withdrew the $250 million when it "became concerned about the lack of transparency to some questions we posed as part of our review," said Chase spokeswoman Kristin Lemkau in a January 2008 New York Times article. A Chase spokesman did not comment further. Fairfield had no comment.

The International Money Laundering Abatement and Financial Anti-Terrorism Act of 2001 makes it illegal for a bank to accept funds it knows, or has reason to believe, were derived from fraud. In addition, it's obliged to report its suspicions to authorities. A tangle of federal and state agencies could investigate such potential banking duplicity, but for national banks like JPMorgan Chase the first overseer is the Department of the Treasury's Office of the Comptroller of Currency. OCC examiners conduct on-site reviews of national banks and provide supervision of bank operations. For OCC to investigate, it must first get a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) from the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), also part of Treasury. But for FinCEN to act, it must receive a confidential SAR from a bank. No report, no investigation. In the case of JPMorgan Chase, SARs are issued by the director of global anti-money-laundering, William Langford. Langford was not available for comment. Spokesmen for both OCC and FinCEN could not comment.

To a nonbanker, what quickly becomes apparent is that the elaborate and formal process for banks' reporting suspicious characters makes it quite possible that a quiet, close-to-the-vest player like Madoff who is not part of any global crime syndicate could operate comfortably for a long time and have a happy bank as his unwitting accomplice. Perhaps in this new push to reform bank practices, that process is worth revisiting.

Robert Chew is a former investor with Madoff via a feeder fund. He lives in Colorado.