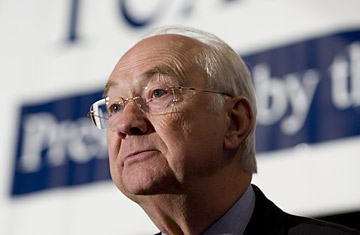

Phil Gramm

The current financial crisis is not all Phil Gramm's fault. Who says? Well, Phil Gramm says. Big surprise. But in a lengthy defense of his record and analysis of the current mess Friday afternoon in Washington, Gramm did allow that it might be at least a teeny bit his fault. Call it the beginning — maybe — of the nuanced consideration of the causes of the crisis that was impossible during the fall election campaign.

As chairman of the Senate Banking Committee from 1995 through 2000, Gramm was Washington's most prominent and outspoken champion of financial deregulation. He played the leading role in writing and pushing through Congress the 1999 repeal of the Depression-era Glass-Steagall Act that separated commercial banks from Wall Street, and he inserted a key provision into the 2000 Commodity Futures Modernization Act that exempted over-the-counter derivatives such as credit-default swaps from regulation by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). (See who's to blame for the current financial crisis.)

Now these laws are under fire, cited by critics — mostly but not exclusively on the political left — as major precipitating causes of the financial meltdown. And while both were signed into law by Bill Clinton, Gramm has taken the most heat. (It hasn't helped that, since leaving the Senate in 2002, he's been working for Swiss banking giant UBS, which has sustained huge losses on bad mortgage securities and derivatives.)

So the American Enterprise Institute, a right-leaning think tank, invited Gramm in Friday to make his case and take some questions. The crowd was heavy on the conservative Washington notables — Cato Institute chairman emeritus William Niskanen, McCain campaign talking head Nancy Pfotenhauer and Iraq War architect Paul Wolfowitz were three that I recognized. But rabble off the street were welcome as well. (Read a critique of Phil Gramm's explanation of the financial crisis.)

Gramm, who before he got into politics was an economics professor at Texas A&M, took to the task with relish. He was dismissive of the charge that Glass-Steagall repeal has been a big problem. "Europe never had Glass-Steagall," he said. "So why didn't this happen in Europe rather than here?" On derivatives he was a bit more nuanced: All he and the Clinton Administration were trying to do with the 2000 bill, he claimed, was establish that interest-rate and currency swaps — two relatively uncontroversial forms of over-the-counter derivatives — couldn't be regulated as futures by the CFTC. At the time, credit-default swaps weren't on the radar, and the bill didn't prevent the Securities and Exchange Commission or bank regulators from stepping in with new rules.

They never did so, and Gramm acknowledged that the credit-default swaps market as it developed was "so opaque that nobody knew who was holding the bag." But he said he didn't buy that it was a major precipitating cause of the crisis. What was? "It was a confluence of two forces," he said. "Alone, neither would have created a cataclysm."

One force was a Federal Reserve interest-rate policy that was appropriate for the previous "inventory cycle" recessions since World War II, but didn't fit at all the collapse of a speculative bubble in the stock market in 2001 and 2002. Consumers, and the housing market, weren't in a recession at all — and the Fed's super-low rates precipitated a bubble. "We inadvertently stimulated an industry that was already in boom conditions," Gramm said. "This changed everything. It changed consumption behavior, it changed lending behavior."