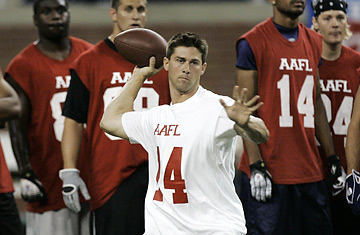

Former Heisman Trophy winner quarterback Eric Crouch throws during a tryout for the All American Football League.

Football may be the true national pastime, but the field is littered with upstart pro leagues that have failed in efforts to capitalize on the wild popularity of the NFL. The USFL, the high-scoring, higher-spending outlaw from the 1980s, folded after a jury awarded it $1 in an antitrust suit against the NFL. The World League of American Football started in the early '90s, morphed into NFL Europa, and got sacked for good earlier this year. And who could forget the XFL in 2001? Near-naked cheerleaders and players named "He Hate Me" couldn't lift record-low television ratings that quickly forced it out of business.

Given that sorry losing record, why in the world are some entrepreneurs planning to kick off not one but two new leagues in 2008?

The eight-team United Football League (UFL), brainchild of financier and former USFL minority owner Bill Hambrecht, will play games during the NFL season on Fridays, when the NFL, and most colleges, are idle. The league will have teams in large metropolitan areas that have no NFL franchises, places like Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and maybe even Mexico City or London. To gauge fan interest, and help the league decide where to place franchises, the UFL will roll out a futures market this week at ticketreserve.com. Fans in 12 cities, including Los Angeles, Austin and Columbus, Ohio, can pay as little as $5 for the right to purchase seats down the road. If a city is not selected for a franchise, the fan gets a refund.

The other upstart, the fledging All American Football League (AAFL), has a very different model. Funded by San Diego entrepreneur Marcus Katz, the AAFL will play in college football hotbeds on otherwise sleepy spring Saturdays, and feature alums from big-time schools like the University of Florida and University of Tennessee on its pro teams. Katz, who made his fortune in the student loan business, grew up an avid University of Georgia football fan, and he's trying to profit from the love fans have for former college players. Since there aren't enough NFL spots for all the talented University of Florida football players, the thinking goes, why not have some of them come to Gainesville, suit up in Gator blue, and play for the Florida AAFL team? They'd face off against teams from Tennessee and Alabama, just like the good old days.

But is that s enough to sustain an entire pro league? "I'm skeptical that there's really an unmet need for more football," says Paul Swangard, managing director of the Warsaw Sports Marketing Center at the University of Oregon. Though both leagues swear they won't repeat the mistakes of past ventures — the overspending of the USFL, the gimmicks of the XFL — even an impeccably run operation may fall short. After all, during the fall, big-time college football essentially functions as a second pro league. And in the spring, when the AAFL plans to play its games, baseball and basketball dominate the attention of sports fans. Neither league has yet to strike a TV deal, though each claims to be working on one.

These formidable obstacles haven't stopped either league from talking a big game. "We're not reinventing the wheel," says Keenan Davis, the AAFL's vice president of football and business operations. "All we're doing is extending the college brand to a professional football league. We're going to have a lot of fun in places where football rules."

The AAFL is certainly the more innovative concept of the two new leagues, though its requirement that every player be a college graduate seems a bit odd — at the pro level, fans don't really care if a player skipped commencement. Responds Katz: "There's so much negative press about the athletes who get in trouble, about how many of them don't graduate. Why not set a good example?"

The AAFL has plans for six teams in its first year. Florida and Tennessee will play on the campuses of those universities, in Gainesville and Knoxville, respectively, and don the colors of the schools. Alabama and Arkansas will play in municipally owned stadiums in Birmingham and Little Rock that have a history of hosting college games. The league is also close to signing deals for the Michigan team to play at Ford Field in Detroit, and the Texas team to play at Rice Stadium in Houston. It's still uncertain if Alabama, Arkansas, Michigan and Texas will wear the exact colors of those big state schools, but expect the uniforms to strongly resemble them, and expect a host of alums from those institutions to suit up. The AAFL will follow a "single-entity" model — Katz will basically own all the teams. He anticipates $12 million budget for each team, and players will make about $50,000 for a 10-game regular season.

For Katz, the college connection is the league's chief selling point. "There's not going to be any rap music," he says. "I don't mean that as a negative against people that like rap music. It's just — no artificial noisemaking. The idea is for it to be just the fans and the band." How important are the trombones? Under the AAFL's deal with the University of Tennessee, the league will pay the school $3 million to use the 102,000-seat Neyland Stadium — minus $100,000 for every game the Volunteer band can't play.

While the AAFL boasts the more original plan, the UFL will win the funding game. Hambrecht plans to require each of the eight owners to invest $30 million, and the UFL will try to float a $60 million IPO for every franchise, giving teams $90 million in up-front cash. "My theory is that public ownership for [sports] franchises is inevitable," says Hambrecht, who got rich advising companies on their IPOs. "The money has just gotten so big. I don't care how rich you are, billion-dollar checks make people think. If you can raise the money in a public security, people don't have to commit these huge amounts of money that are locked up and have no liquidity."

It's an ambitious plan for a start-up, but given Hambrecht's big-money connections, don't be surprised to see him pull it off. Hambrecht and his partner, Google ad sales president Tim Armstrong, have already put down $9 million. Mark Cuban, the madcap owner of the Dallas Mavericks, will likely buy a team. Michael Huyghue, a veteran NFL exec and player agent who was recently named the UFL's first commissioner, says Cuban is not the only NBA owner interested. The UFL wants to offer $1 million salaries to at least 10 players on each team, which should be enough to lure a few mid-level NFL players to the nascent league.

Both leagues carefully insist they will complement, not clash with, the NFL. Davis, the AAFL business chief, laughs when informed of the UFL's philosophy. "They're playing at the same time," he notes of the UFL's slate of fall games. "What's their schedule, and what's the NFL's schedule? What do you call it? They're 'playing alongside' the NFL?" Huyghue insists he can't touch the big boys. "Our salary cap is somewhere around $20 million, they are around $110 million," he says. "I wouldn't really call that competition."

Despite all prior evidence to the contrary, each league is banking that there's plenty of pigskin passion to go around. "It's just like poker," Huyghue says of football fanaticism. "You think people are going to get enough, and at 3 in the morning, they are still in their underwear, playing at their computer." AAFL founder Katz is almost wistful. "I don't really even care about the money," he says. "Winning is having more games to go to." If pro football history is any guide, he may be going alone.