|

A pioneer of the comix form, Tezuka (1928-1989) has been enjoying a spate of U.S. releases in the last couple of years. Dark Horse continues to publish his Astro Boy series (see TIME.comix review) while Vertical Inc. just released volume four of the gorgeous eight-volume "Buddha" series (see TIME.comix review). Meanwhile VIZ has been publishing the first of the "Phoenix" books — the master's unfinished, twelve volume magnum opus. The fourth, "Phoenix: Karma" (366pp; $15.95) has just been released. The fifth volume, "Resurrection," is due in November. (Sadly, the remaining seven have not yet been contracted for publication.) While doing other projects, Tezuka worked on the series from 1967 until his death. Though each story stands independent of the rest, they remain interconnected by the appearance of the titular bird and other recurring characters, as well sharing Tezuka's humane and philosophical themes. The latest, "Karma," has a reputation as the best of the lot, and it is indeed a masterpiece.

The "Phoenix" series alternates between past and future stories that range from 240 A.D. to 3404 A.D. "Karma" takes place in 8th century Japan. It begins cruelly as the newborn Gao tumbles down a rock face when his father slips while on the way to pay homage to the mountain spirit. Fifteen years later, the one-armed, one-eyed Gao has become the village pariah. When their scorn becomes more than he can bear he unleashes a savagely violent revenge that begins his days as a hunted, merciless bandit. And yet, in a moment that I missed on the first read, during a breathless chase scene, he puts a ladybug out of harm's way. During his travels Gao crosses paths with Akanemaru, a sculptor on his way to visit a temple. Akanemaru shares his campfire, a kindness that Gao returns with a hateful crippling of the "proud" sculptor's arm. From here the book switches back and forth between the lives of both men. They will meet twice more, fulfilling separate but strangely parallel destinies.

Gao chases Baya through the snow

Gao chases Baya through the snow |

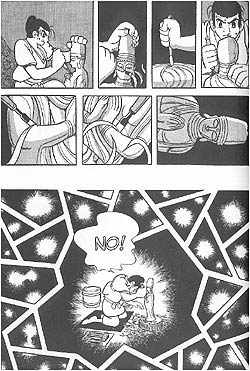

At first devastated by his loss, Akanemaru finds the inner strength to continue his work while convalescing at a Buddhist monastery. Soon a powerful prefect "commissions" him, under the threat of death, to sculpt the legendary Phoenix. Given three years to accomplish this, Akanemaru begins a quest to find the bird. Meanwhile Gao falls in love with a Baya, a woman who appears from nowhere and becomes his captive. When Gao gets an infection of the nose (it balloons to resemble a hideous eggplant in a typical bit of Tezuka humor) he mistakenly believes Baya to be the cause. In a masterful scene of beauty and brutality, the furious Gao chases Baya through a snowy forest. Her blood spills over the white ground as her spirit escapes in an explosion of paisley patterns. She dies and, in a succession of increasingly smaller panels, she transforms into the husk of a ladybug. At once Gao realizes that all life, those of insects and men, have equal value. It is as great a transformative moment as any to be found in fiction.

So begins Gao's slow reformation. Upon learning of the wheel of karma, wherein the things we do in this life affect our reincarnated form in the next, Gao travels Japan as a wandering monk's acolyte. Along the way he discovers his own talent for sculpting. Meanwhile Akanemaru has a vision of the Phoenix, a bird who represents the eternal reborning of all life. His carving of the bird earns him a commission from the emperor to oversee the construction of a giant Buddha. Eventually, after many more twists, Gao and Akanemaru meet for the last time in a contest to see who can better carve the gargoyles for the roof of the giant Buddha's temple. The book climaxes with a savage act of violence, followed by a denouement of karmic justice and tranquility. In the end, art and compassion become the redemption of all.

Akanemaru struggles to carve a Boddhisatva

Akanemaru struggles to carve a Boddhisatva |

One can barely touch upon the depths of this deeply sophisticated work in the confines of a review. It would take something more along the lines of an exegesis. Tezuka has created a book that combines the excitement, plotting, and characterization of the best novels with the philosophy of the best spiritual essays and the beauty of the drawn arts. Among other themes, "Karma" manages to be about the role of the artist in society, the relationship between religious experience and human endeavors, the misuse of religion for the sake of power and the importance of trying to lead a moral life. Wisely putting the needs of good art before the needs of religious instruction, Tezuka avoids the didactical trap of American religious comics. Using his unbeatable powers of the comic arts, he keeps the story moving at a clip while also managing to create two complex and flawed heroes and getting across the lessons of Buddhism. That he does all of this with a seriousness of purpose tempered by a light-hearted wit keeps one excitedly turning the pages in anticipation of the next miraculous moment.

This counterpoint of seriousness and play manifests itself most fundamentally in the artwork. The characters appear mostly in a silly "cartoon" style, with tropes like exaggerated brows, buckteeth and expressive eyes. (Tezuka defies expectations of what Japanese "manga" looks like.) These caricatures are then set against highly detailed backgrounds, with Tezuka often taking extra panels, or even entire two-page spreads, just to linger on the environments. He has such a mastery of the form that while providing every necessary panel to tell the story he has extra space just for breathing room. A temple sits stoically in the woods, or flowers blow in the breeze, or a moth gets caught in a spider web. Tezuka may also be the supreme master of dynamic yet readable layouts — a talent that reaches its pinnacle in "Karma." No two pages have the same design. Particularly frenetic sequences inhabit small, jagged panels that work like a strobe light on an action too fast for the eye to see. When Akanemaru despairs of finding the Phoenix he sits at the bottom of tall, full-length panels that make him seem tiny. But much of this will go unnoticed the first time through. Your eye dances through the pages like a supple partner to Fred Astaire's lead.

Though better than having nothing, it is unfortunate that VIZ has not put more care into the packaging of "Karma" and its related books. Bizarrely, they released volume two first, at a larger format and higher price point than the others. Then came volume one, three and four respectively. (They plan on reprinting volume two at the same size and price as the others.) Printed as paperbacks with an ugly cover design, none of the volumes can be distinguished from the others except by careful examination of the subtitle and the numeral on the spine. Furthermore, without the promise of the remaining seven volumes, VIZ has almost completely botched an opportunity to distinguish themselves from their principal competition (TOKYOPOP) as a publisher of classy, adult Japanese comic art.

Osamu Tezuka's "Phoenix: Karma" reaches near nirvanic heights. As entertaining as any comic can be, it miraculously also achieves what lesser religious comix strive for and fail at: enlightenment. Though it seems doubtful that readers will change their lives thanks to "Karma," they cannot avoid being touched by its deeply humane philosophy and egoless artistry.