Sana Kurata from "Kodocha"

Sana Kurata from "Kodocha" |

Printed as cheap, multivolume paperbacks and sold at major bookstores, manga have ignited graphic-novel sales around the world. In the U.S. last year manga racked up some $100 million, almost double 2002's sales, according to ICv2, a pop-culture trade publication. The two dominant U.S. publishers of manga, TOKYOPOP and VIZ, will ramp up their 2004 title count to more than 300 between them. Later this year DC Comics plans to launch a manga imprint called CMX.

Shojo manga are a big part of that boom. Mostly written and drawn by women, shojo usually put cute, strong-willed 13 to 16 year old girls at their center. The stories typically focus on relationships and romance, but often also include adventures in magical worlds outside the humdrum realities of school and home. Mecca Moore, 13, of Los Angeles, buys manga every week and claims to spend $1,000 a year on the stuff. She says she likes shojo because, "They tell a story in art that makes a person have a special connection. You can actually feel what the character's feeling and see what the character's thinking."

Eve Zimmerman, who teaches a course on "Gender and Popular Culture in Japan" for Wellesley college's Japanese department, sees shojo's appeal from a more distanced perspective. "Shojo manga are popular because they tap into the social obstacles and challenges that girls face: feeling excluded by cliques, having crushes on boys, and often wrestling with issues of their own sexuality," she wrote me in an email from Japan. She continued, "But they are also popular because they present a glossy image of a different kind of existence where everyone dresses up fashionably and looks cute."

|

VIZ's currently top-selling shojo title, "Fushigi Yugi: The Mysterious Play," by Yu Watase, typifies the style. Deftly combining action with melodrama, it tells of Miaka Yuki, a lazy student with exam nightmares. A strange library book allows her to visit ancient China where she meets a handsome but avaricious young warrior. Like most shojo the style of Fushigi Yugi includes lush costumes, impossibly beautiful boys and, yes, those big, saucer eyes and tiny, button noses. What new readers may be surprised at are the frequent shifts into goofball humor and the author asides -- both of which are manga tropes.

|

TOKYOPOP's big release of the new year will be the first volume of Natsuki Takaya's "Fruits Basket," coming out this month. One of the biggest-selling shojo titles in Japan, it features Tohru Honda, an orphaned junior-high student who discovers that the cutest boy in school turns into a rat whenever hugged by a member of the opposite sex. Far from repulsed, she moves in with him, as a housekeeper, and discovers an entire family cursed to turn into animals at the most awkward times.

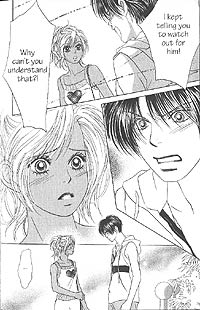

Momo and her boyfriend Kiley, from "Peach Girl"

Momo and her boyfriend Kiley, from "Peach Girl" |

As an adult male, I have to admit that after reading nearly a dozen different shojo titles I find it impossible to critically distinguish between them all. Like the male-targeted superhero books, none of them achieve much more than being amusing but disposable entertainment. The better ones stand out for the quality of the artwork and clarity of storytelling. Miwa Ueda's "Peach Girl" (TOKYOPOP), about the overly dramatic personal life of high-schooler Momo Adachi, seems a cut above with excellent art and slightly more mature themes. For younger readers, Miho Obana's "Kodocha: Sana's Stage" (TOKYOPOP) about a precocious child TV star with trouble at school, has a lot of comedic charm.

|

One surprisingly big seller for TOKYOPOP is "Gravitation" by Maki Murakami. It falls into a splinter genre of shojo called shonen-ai, translated literally as "boy-love." Though targeted at girls, shonen-ai features the romantic relationship between two males, in this case between high-schooler and aspiring musician Shuichi and a slightly older romance novelist named Eiri Yuki. Though it features a passionate kiss, "Gravitation" and other shonen-ai never get sexually explicit. The appeal for girls seems to be in looking at two pretty boys entering into an untouchable romance. Though quite popular in Japan, very little shonen-ai has gotten translated into English.

|

American-born shojo talent has also begun to emerge. Jill Thompson's manga-style book "Death: At Death's Door" became one of DC Comics' best sellers last year. Using the popular goth-girl character from Neil Gaiman's Sandman universe, "At Death's Door" tells of Death's struggles when her brother Morpheus takes over Hell. "One of the reasons I like manga is there are just pages and pages of characters regarding each other," Thompson says. "You can flip through them fairly quickly but you feel a lot of emotion without having to read words. I've always liked art like that."

Reading manga has inspired Mecca Moore to do her own art. "I have a whole book of manga stories I keep and ideas that I want to get published some day," she says. "Sometimes they're superhero stuff and sometimes they're just like everyday life. I try to get different people's perspective." She says she wants to be a manga-ka, or professional manga artist, not later but now.

Shojo comics have little in common with the corny romance titles of yesteryear. These books are for an audience like the characters they depict, independent-minded girls for whom romance becomes another complication in a busy life.

This is an expanded version of an article that appeared in the February 16, 2004 issue of TIME Magazine. The original article can be found here