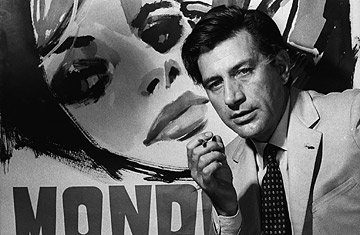

Gualtiero Jacopetti, film director of Mondo Cane, 1963

(3 of 3)

Determined to prove their racial liberalism, the filmmakers thought they had another great idea: as Prosperi said, "Why don't we do Mandingo as documentary?" Kyle Onstott's 1957 novel about sex, violence and slavery on an Alabama plantation would become a Hollywood movie in 1975, but Jacopetti and Prosperi got there first and went further. Addio zio Tom, shown in a shortened American cut as Goodbye Uncle Tom, borrowed the time-traveling doc style of the CBS show You Are There, but in scope and ambition it was one of the boldest of all mockumentaries, and one of the earliest (after Woody Allen's Tale the Money and Run).

In the first scene, the Italian filmmakers helicopter low over plantation fields, the blades stirring dirt into the faces of the slaves — suggesting that the film will both sympathize with the slaves and somehow tarnish them. The camera then enters the master house, where fancy-dress white people sit at dinner. "These gentlemen are my guests," the matronly hostess tells the others at the table, "so they can learn who really are the slaves and masters here." When a woman supposed to be Harriet Beecher Stowe argues against slavery while a "professor" states that "God is white, and as long as God is white we shall prevail of all other races," an elderly black servant stares glumly, three black boys fan the guests and two others are fed chicken bones under the table.

The movie was shot in Haiti, where Jacopetti and Prosperi were guests of Papa Doc Duvalier; they were given diplomatic cars, the run of the island, as many extras as they wanted and dinner every Friday with the dictator. Addio zio Tom says that slavery was bad, but that watching torture — the degradation of humans by humans of a lighter hue — has a therapeutic value to the viewer. Scene after scene depicts the selling of naked black men and pregnant women by the ruling class. Ogling is encouraged in a film that's still supremely difficult to watch; the camera considers the whites with a sneer and the blacks with a leer. Frattari, the Mondo Cane cinematographer, worked briefly on the shoot and later said, "The film was born bad and was going to end up worse."

Banned or severely cut in several countries, Goodbye Uncle Tom in all its excess provoked Ebert to a level of disgust that made his Africa Addio review seem mixed. "The vile little crud-squad of Jacopetti and Prosperi" have produced a "vomit-bag of racism and perversion-mongering. the most disgusting, contemptuous insult to decency ever to masquerade as a documentary." He called the employment of Haiti's poor in the film "cruel exploitation. If it is tragic that the barbarism of slavery existed in this country, is it not also tragic — and enraging — that for a few dollars the producers of this film were able to reproduce and reenact that barbarism?" If the film is recalled fondly today, it is for Ortolani's rapturous score; the movie's theme song, "Oh My Love," appears on the soundtrack of the new Ryan Gosling film Drive.

Uncle Tom was a flop and an embarrassment, and the last of the Jacopetti-Prosperi collaborations. A feud between the two had simmered for years, but hit films and a shared view of the medium's subversive possibilities kept them together. After they split, neither reached the heights of their early successes, and Jacopetti returned to print journalism. But a movie career doesn't need a happy or tragic ending to give it significance. Once upon a time, Jacopetti created a movie that altered, arguably liberated and certainly coarsened popular culture. He made the world Mondo.