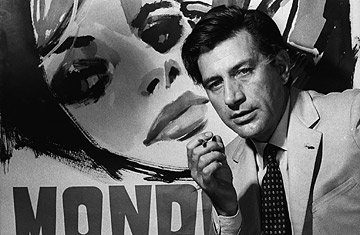

Gualtiero Jacopetti, film director of Mondo Cane, 1963

"Mondo," being the Italian word for world, should be a neutral noun. Yet go to any modern dictionary and find a variety of definitions far from the original. "Adjective: enormous; huge; extremely unconventional or bizarre." "Adverb: Used in reference to something very striking or remarkable of its kind." The Urban Dictionary provocatively calls Mondo "the quintessential word of the English language." What all contemporary linguists agree on is that it derives from the 1962 "documentary" Mondo Cane. So it's worth recognizing the film's writer and supervising director, Gualtiero Jacopetti, who died Aug. 17 at 91.

Born in Barga, Tuscany, in 1919, Jacopetti served in the Italian Resistance during World War II and co-founded the liberal newsweekly Cronache in 1953. He worked on newsreels, and a couple of docs about the seamier night clubs on five continents, before having his eureka-Mondo inspiration. "Let's make an anti-documentary," he told his colleague Franco Prosperi, who would be Jacopetti's codirector for the next decade. The result was Mondo Cane, which means Dog World in Italian — "an ironic, mocking, even cynical title," Jacopetti recalls in David Gregory's exemplary 2003 doc The Godfathers of Mondo — but which was released in English-speaking countries under its original title. Hence, Mondo.

Jacopetti wasn't the first filmmaker to marry sensation to documentary. The early shorts produced by Thomas Edison's company opened viewers' eyes to cockfights, cootch dancers and, in 1903, the electrocution and death of Topsy, a Coney Island elephant. Audiences loved that the movie camera could take them places they'd never been and show them things they'd never seen, and in 1922 they got their first feature-length true-life adventure. In his ethno-smash Nanook of the North, Robert Flaherty filmed the working and community life of an Inuit fisherman in faithful detail — except that the Eskimo wasn't named Nanook, and many scenes were restaged for the camera. Flaherty believed a filmmaker had to bend certain facts to tell a larger truth, and the documentary ethos would henceforth pirouette between reportage and reenactment.

Cellar-dwelling filmmakers soon added the erotic to the exotic. J.C. Cook's 1934 Inyaah (Jungle Goddess), which intercut stock footage with a location shoot in Indonesia, purported to record the strange folkways of tribal races, where the men are fierce and the woman pretty and topless. The peculiar American mores of the time forbade nude images of whites but saw ethnographic value in shots of unclothed African or Asians; it's one reason many boys became connoisseurs of photo spreads in the National Geographic. Exploitation movies just upped the ante: to National Pornographic — a tendency Jacopetti and his team would bring to cinematic fruition.

Jacopetti expanded that adolescent voyeurism to the whole world. "Cinema," he said, "was the perfect medium to tell the facts of life," and he'd tell them all. Jacopetti and his team — Prosperi, second codirector Paolo Cavara and cameramen Antonio Climati and Benito Frattari — circled the globe for lurid scenes, acting like the nerviest tabloid photographers whose only goal was to get the story. "Back then the whole world was unprepared for our shooting strategy," Prosperi says in The Godfathers of Mondo. "Slip in, ask, never pay, never reenact." (Well, maybe sometimes they did stage reenactments, but, hey, so did Flaherty.) Mondo Cane upended the Italian film tradition of neorealism — movies on working-class themes shot in a naturalistic style — for a kind of sociological hyperrealism.

In the process it defibrillated the staid documentary tradition: here were startling images, abrupt juxtapositions, the violent voyeurism of the new zoom lens and Jacopetti's scathing narration. TIME's review of the film gave a hint of the filmmakers' dialectical scheme: "After ogling a beachful of bikinied bosoms, the camera cuts abruptly to a woman in New Guinea nonchalantly nursing a small, bristly pig, cuts again to a nearby village, where screaming hogs are being clubbed to death by natives in preparation for a barbecue." Wrote the magazine's unnamed critic: "If there's a message, it's that people are no damn good." And yet, as Michael Weldon noted decades later in The Psychotronic Video Guide, "There's sense and irony in everything, The film made audiences think while shocking them."

The movie's opening narration read: "All the scenes you will see in this film are true and are taken only from life. If often they are shocking, it is because there are many shocking things in this world. Besides, the duty of the chronicler is not to sweeten the truth but to report it objectively." The objectively reported truths included such antic behaviors as snake-eating, bull-goring, pet necrophilia, a woman suckling a pig, livestock beheaded with a sword, a restaurant that serves canned ants, an artist who paints nudes. Paints their nude bodies blue, that is.

Jacopetti also hired the composer Riz Ortolani to write a full, Hollywoodish score, whose inappropriate but irresistible love theme "More" ("More than the greatest love the world has known") was nominated for an Oscar and went on to be played at nearly every wedding for the next 20 years. This weird mix of horror and humor — that you could hum to — made Mondo Cane a worldwide hit. The Guardian's Mark Goodall fairly pegs it as "the strangest commercially successful film in the history of cinema."