(4 of 5)

Fan fiction that isn't constrained by canon is known as AU, which stands for Alternate Universe, and in AU all bets are off. The canon is fired. Imagine how Harry Potter's story would have played out if on his first day at Hogwarts he'd been sorted into Slytherin instead of Gryffindor. Or if he were a vampire, or a werewolf? Or for that matter, what if he were black? Or if instead of trying to kill baby Harry, Voldemort adopted him, raised him as Harry Marvolo and conquered the entire British Isles? (This scenario has been intensively explored in a group of fan stories known collectively as Alternity.)

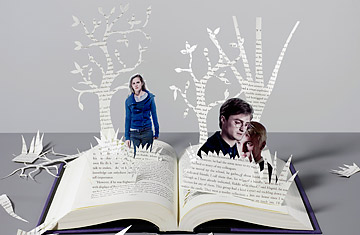

In AU, the writer's readerly id takes full control and, unrestrained by the superego of canon, runs riot. It annihilates the conventional set of literary genres and organically makes up new ones, which form a kind of map of human fictional compulsions. "Hurt/comfort" stories revolve — as you might imagine — around one character's getting injured physically or emotionally and another character's providing solace. There are "genderswap" stories and "bodyswap" stories (figure it out). In fan fiction, all fictional universes adjoin one another and characters slip through; "crossover" stories connect the world of, say, Harry Potter with that of, say, Anne of Green Gables or the Halo games or The West Wing or The Catcher in the Rye or Pride and Prejudice. Even reality is just another genre: that's RPF, or real-person fiction. RPF includes bandfic, which deals with the lives of real-life rock stars. There are stories that, executing a twisting narrative backflip, dump Daniel Radcliffe and Rupert Grint directly into Hogwarts alongside the characters they play in the movies (à la "Visit to a Weird Planet").

There is, of course, a ton of sex in fan fiction. It's a monument to the diversity of human sexual whim. There are stories that take any and every character you can name and pair them up romantically or erotically or pornographically. (One of the axioms of Internet culture is known as Rule No. 34: "If it exists, there is porn of it.") A lot of alien plants turn out to produce pollen with powerful aphrodisiac effects. You'd be amazed.

And that's the tame end of the spectrum. Fan fiction mines some dark veins, and you can follow them down as far as you want. Wherever you choose to stop, you'll see that somebody else has gone further. Incest is not off-limits (nor is "twincest"). There's a genre called Mpreg, which is about male characters getting pregnant, and it's way more popular than you'd think. There is such a thing as "dubcon" (short for dubious consent) and "rapefic." Responsible writers of explicit fan fiction add warnings to their stories. At the well-curated fan-fiction website Archive of Our Own, the menu of possible warnings includes "Graphic Depictions of Violence," "Major Character Death," "Rape/Non-Con" and "Underage."

Something Borrowed, Something New

All this discussion of the richness and complexity of fan fiction leaves out the pressing questions of whether fan fiction is legal or ethical. The key legal issue is, of course, copyright. In the U.S., at least, copyright is checked by something called fair use: if a work qualifies as fair use, it can borrow from a copyrighted work without permission and without paying for it. There are four factors that determine whether a work qualifies, the most germane here being whether it can be considered competition for the original work in the marketplace, and whether it's "transformative": it has to change what it borrows, making "something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message." (The words are those of Supreme Court Justice David Souter in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music Inc., which concerned whether 2 Live Crew's "Pretty Woman" made fair use of Roy Orbison's "Oh, Pretty Woman." The court decided unanimously that it did.) Does fan fiction transform, or does it merely imitate? Is it critique or just homage?

There are plenty of major writers who can't abide fan fiction based on their work. They post statements about it on their websites. Orson Scott Card, author of the classic Ender's Game books, has written, "I will sue, because if I do NOT act vigorously to protect my copyright, I will lose that copyright ... So fan fiction, while flattering, is also an attack on my means of livelihood." Anne Rice is every bit as vehement: "I do not allow fan fiction. The characters are copyrighted. It upsets me terribly to even think about fan fiction with my characters. I advise my readers to write your own original stories with your own characters."