I don't watch Saturday Night Live. I don't own a television, but I do own a 10-month-old baby, so you do the math. But that didn't stop me from being riveted, absolutely riveted, by an oral history of the show called Live from New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live, by James Miller and Tom Shales, published in 2002. Until then I didn't realize that Chris Farley's pooping out a 17th-story window of Rockefeller Center was something I needed to know about. Turns out it was.

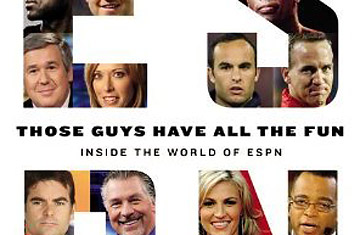

Now Miller and Shales have given ESPN the same treatment in a book called Those Guys Have All the Fun: Inside the World of ESPN, and the results are almost as good. Their MO is to talk to pretty much everybody who's ever been anywhere near the network and then weave the quotes into a single (nearly) seamless narrative, presented verbatim with little commentary, focusing on key transitions and deals and famous and infamous moments. (Their technique owes a lot, unless I'm mistaken, to the work of the great Studs Terkel.) It's a revelation: what goes onto the TV screen is just the glossy tip of an iceberg of ugly backstage drama. Miller and Shales must be extraordinarily talented interviewers, because their subjects are surprisingly uninhibited and frank and willing to dish and slag. There are some great gets in Those Guys Have All the Fun: we hear from the gimmes, on-air talent like Dan Patrick and Keith Olbermann, but also from high-level executives, past and present, and there are cameos from the likes of Rush Limbaugh, Dave Eggers, Malcolm Gladwell and Barack Obama (who comes out in favor of a playoff system for college football). It's unauthorized, but the access is legit.

The SNL book worked because SNL was a little world unto itself, a bunch of freak-show geniuses locked in a room together. Miller and Shales let you into the room. There's a room in this story too: Bristol, Conn. ESPN was the brainchild of Bill and Scott Rasmussen, a father and son, and two cable-TV outsiders (Bill, the dad, had recently lost a job as communications manager for the Hartford Whalers). They set up shop in 1979 on redeveloped land in tiny, obscure Bristol. "What a s--- hole," says Bill Creasy, a vice president of programming at ESPN. "I mean, what were they thinking?" Pretty much everybody subsequently quoted in the book complains about how remote and dead Bristol was, but the lack of distractions meant that staffers breathed, slept, ate and especially drank ESPN all day, all night, all week, all year.

It's bizarre how close ESPN came to not happening, given what an obvious slam dunk it looks like in retrospect. But in 1979, the cable market was tiny, nobody understood satellite technology very well and nobody would give the Rasmussens the $15 million they needed to get started. ("There's already an awful lot of sports on television" was a typical reaction.) It was eventually backed by Stuart Evey, an executive at, of all places, Getty Oil. Evey was an epic drinker. Poor Dick Ebersol, who until recently ran NBC Sports, recalls meeting with Evey about a job and having to go to the bathroom to throw up in the middle of it, just so he could keep going.

The beginnings were humble. No one seems sure, but the first event the network taped was probably the American Legion World Series in Greenville, Miss. "We had four cameras," the director remembers. "Only one of my four cameramen had ever shot baseball before, the remote truck was an old converted school bus, and we rolled in there and no one's ever heard of ESPN." The home-plate camera filmed through the backstop. The first night ESPN was on the air, the building was still under construction, and a bulldozer ran into the remote truck. Australian rules football was an early programming staple.

The culture in Bristol was intense, and intensely male. Betting on games was epidemic. There were drugs. There was sexual harassment. There was sex in the stairwells. "We had no social life because we worked all the time," an early director of production says. "There were a lot of interoffice romances going on because you didn't have a chance to meet anybody else ... People who you never thought would get divorced were getting divorced, and a lot of those guys didn't have any regard for women." The company kept an apartment in Manhattan, and at one point it came out that some of the secretaries were turning tricks there, pimped by a guy in the mail room.