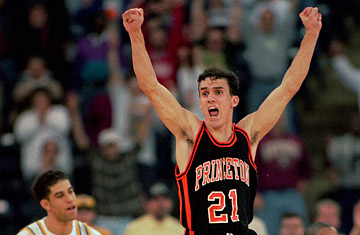

Princeton guard Mitch Henderson jumps in celebration of the Tigers' victory over UCLA in the first round of the 1996 NCAA men's basketball tournament

(6 of 6)

Why'd You Do It to Me?

In a burst of guttural joy, our bench rushed midcourt — if we ran that fast during practice, perhaps we'd be playing more. We were intent on tackling the Princeton players. Are you kidding? These guys just pulled this off? CBS seems to replay our hysteria every March, which has become somewhat embarrassing for me: "Hey, I saw you running off the bench against UCLA last night." You only need so many reminders about your lack of impact on a game. But our spontaneous charge conveyed a team's true sense of affection for one another.

When the buzzer sounded, Henderson instantly leapt off the floor and raised both his fists into the air. The lens of Tom Russo, a freelance photographer for the Associated Press, was homed in on Henderson the entire last play. "As you watch the games, you try to figure out who is really emotional, and hope you pick the right guy," says Russo, now a staff photographer for the Daily Reporter of Greenfield, Ind., an Indianapolis suburb. "It seems that guards get more excited than the big guys. I don't know why." Russo knew he caught Henderson's leap, but when he dashed back to the darkroom, he prayed for UCLA anguish in the background.

Russo furiously flipped through the photos. He got it! To Henderson's right was Bailey, fresh off an air ball, shoulders slumped, mouth open, hands on his shorts, as if he just got ditched at the prom. Russo's picture may be the most iconic image in Princeton history. The picture ran in papers across the country, and was planted onto countless cups and T-shirts on campus over the next few years.

Carril smiled and waved around the program that he clutched the entire game. His utter delight was such a rare sight: this was a man who once said, when his team was undefeated in the Ivy League, "These are tough times for a pessimist." He got hugs from Thompson and Scott, two of his future successors as Princeton coach, before greeting Harrick for the postgame handshake. "I'm happy for you," Harrick told Carril, in a classy move. As he walked toward more postgame adulation, Carril muttered to himself, "Ay-yi-yi-yi-yi." Later that night, Kevin Gillett, a reserve freshman center, also heard Carril talking under his breath, "I can't believe they f---ing did it. I can't believe these kids f---ing did it."

In the stands, the relatively small contingent of Princeton family members, alums and students — "There might have been 20 of you guys," teases Miller — bear-hugged each other and shed a few tears. Burkett and Douglas, the two sophomores who drove from Princeton to Indianapolis the previous day, tried to storm the court. "We had done that at the playoff game at Lehigh, and were so naive. 'Hey, let's do it here too!'" says Burkett. "But a security guard made it very clear — that just doesn't happen at the NCAAs." Douglas, remembering the pregame taunts of the UCLA cheerleaders, returned the favor. "Looking forward to football season?" he asked. One male cheerleader, flanked by a few burly colleagues, was not amused. "I can't say he was going to kick our ass," says Burkett. "But that security guard who wouldn't let us on the floor — he was now our best friend."

Andrea Joyce, the CBS sideline reporter, interviewed Carril. "I guess that I won't have to be known as the guy who lost every close one," Carril told her. Sydney Johnson and Lewullis also lined up to talk to Joyce. But after Joyce interviewed Johnson, and Lewullis prepared to step up to the mike, Joyce threw it back to the studio, leaving Lewullis hanging on national television. He looked like a kid who got nothing for Christmas: "I made the layup. I'm Gabe Lewullis. What about me?" All of Allentown got a kick out of that one. "I will never talk to Andrea Joyce again," deadpans Lewullis.

Over the next decade, Joyce says more people asked about covering UCLA vs. Princeton than any of the hundreds of other events that she worked, including the Super Bowl and the Olympics. After signing off, Joyce saw Darren Hite, the reserve forward, in the bowels of the RCA Dome, wearing a Princeton basketball T-shirt. She offered Hite some CBS swag in exchange for the shirt. Hite obliged: the sudden cachet of Princeton hoops literally cost Hite the shirt off his back. "All these reporters then gathered around me, wondering what the hell was going on," Hite says.

After game ended, Gus Johnson took off his headphones. "I said, 'Man, Waco, Texas; Huntsville, Ala.; Greensboro, N.C.; Washington, D.C.," says Johnson, rattling off the markets where he had previously worked. "MSG, ESPN and now CBS. I was very aware of the moment, and it's still probably bigger than any other moment I've been a part of while calling the tournament on CBS. I remember saying to myself, 'Man, if it all ended today, I would at least be able to say I had the opportunity to see college basketball at the greatest level there is.' I was just happy."

While Mitch Henderson jumped in the air and Princeton partied, Brandon Loyd, the freshman whom Harrick summoned off the bench to hit a couple of three-pointers in the second half, cried on the UCLA bench. "On the front page of the L.A. Times when we get home, you had Brandon Loyd, snot dribbling out of his nose, tears running out of his eyes, jersey halfway up over his head," says Kris Johnson. "I mean, we never let him let live that down. Come on, Loyd." The shooting guard, now a risk consultant and father of three children in Tulsa, Okla., lost his emotions because he came so close to saving the season. "I didn't have a great freshman year," says Loyd. "And here I was, I finally helped out, and we weren't able to win. I'm a Bambi kind of guy, and it was kind of embarrassing."

The cameras may have caught Loyd crying, but he wasn't alone. "I vividly remember, after the game, dudes were bawlin'" says Kris Johnson. "Dudes were in tears, throwing jerseys and kicking over Gatorade jugs in the locker room. We have this idea of repeating, we had a really good team, we were talented at all positions. We had tasted it the year before. It was this incredible wake-up call. This is reality. Last year was fantasy."

In UCLA's postgame press conference, a student manager from Duke, which had lost to Eastern Michigan earlier in the day, asked Harrick if he felt Carril outcoached him. It was the kind of direct, tough and honest question that any good journalism teacher would encourage. But it's one that rarely gets asked right after the game, at a press conference, when emotions are still raw. The media knows the coach may snap, and sports reporters, no matter how brave they think they are, don't like a public tongue-lashing in front of colleagues. But Nick Silvers, the Duke manager, wasn't worried about the opinion of media peers. Such is the advantage of not being in the press.

Harrick glared at Silvers, now a New York City real estate executive, as time froze. "I'm not sure you are really qualified to ask that question," a furious Harrick told him. (Silvers did not respond to an interview request.) The clip was replayed dozens of times on television; today, it would have instantly gone viral. Much calmer 15 years later, Harrick can still recall the exchange. "I thought, 'I've been asked stupidest question in the world,'" says Harrick. "Look, it didn't bother me that much. I didn't want to go down that road, because if I got outcoached, then after every win can I say I outcoached the other guy? Princeton executed — give them credit for it."

Carril used to say that only nine-headed players would excite Princeton students about basketball. Though the UCLA game exclusively featured players with one noggin, the Princeton campus exploded anyway. Students poured out onto Prospect Avenue, the school's social hub. "The celebration was immediate, and dramatic," wrote the Daily Princetonian. "When a Ryder truck drove through Prospect Avenue, Tiger fans grabbed hold of the still-moving vehicle." On a pay phone, Gillett phoned his roommate, who held the receiver out the dorm-room window, nearly 250 yards away from Prospect Avenue. Gillett could hear the roars.

Over the next 24 hours, the Princeton players were the toast of Indianapolis. That night, Goodrich grabbed dinner with his family and a few friends at a sports bar: the fellow customers clapped for him. While walking around a mall the next day, strangers asked us for autographs and offered hugs. "It was real messed up," says Ben Hart, a reserve forward. Even the bench guys and behind-the-scenes staffers received the unusual attention. Jerry Price, the team's sports-information director, paid for dinner with a Princeton credit card. The waitstaff started asking him questions about the team, the school and Carril. Soon, other diners joined the conversation. "It could have been, 'Are you Tom Hanks?'" says Price.

The team was flooded with interview requests. Price even put Miles Clark, the team's manager, on one radio show. The game was front-page news throughout the country. On Good Morning America, host Charlie Gibson, a Princeton alum and big Carril fan, talked about the game at the top of the broadcast, eyes watering. He watched it in his den the night before, yelling and screaming, alone — permitting others in the room would be too disconcerting. "That morning, the game was the only thing on my mind," says Gibson, who went on to anchor World News with Charles Gibson from 2006 to '09. "It probably cost us a few viewers in Los Angeles, because I was being such a pain the ass about Princeton basketball."

In the team hotel, Carril and the coaching staff stayed up until 5 in the morning after the UCLA game, drinking beer and wine. We would play Mississippi State in the second round, two nights later. "Coach was just content," says Thompson. "We kind of knew that this would probably be it. Mississippi State was just so physically overpowering."

Lewullis, for his part, would have to wash his clothes in the bathtub over the next few days — he packed for two nights, not four. The next day, we practiced at Butler University, while the Pacers worked out at a gym next door. At one point, Miller walked into the gym and approached Carril. "All my teammates rode me," says Miller. "I had to go eat crow and shake the man's hand, the orchestrator's hand. It was a beautiful performance."

It would not be repeated the next night, as Princeton fell to Mississippi State, 63-41, in one of the least depressing losses in school history. The team also took solace when Mississippi State, led by 6-ft. 11-in. Erick Dampier, who is still playing in the NBA, for the Miami Heat, and Dontae' Jones, a first-round pick of the New York Knicks that spring, reached the Final Four.

When UCLA players arrived home, derision awaited in Westwood. "An Ivy League school had beaten the national champs," says O'Bannon. "How do you go back to the hood and validate that?" UCLA fans, and the media, were particularly harsh on Harrick. Although he had become the first UCLA coach to win a title post-Wooden, he was never fully embraced. "Coming back to L.A. after losing a first-round game is no picnic," Harrick says today. "It's brutal — there are piranhas out here. Piranhas."

That game was Harrick's last at UCLA. The school fired him the next fall for falsifying an expense report. University of Rhode Island hired him the next season, and the Rams fell one game short of the Final Four. Harrick moved to Georgia in 1999 and turned that program around before allegations of academic fraud involving his son, an assistant, forced him to resign his last college-coaching position.

Despite losing to Princeton, those UCLA teams deserve recognition for their success. The core group from 1996 — Bailey, O'Bannon, Dollar, Kris Johnson and J.R. Henderson — won a championship in 1995. Those players also made it to the Elite Eight in 1997, under 32-year-old rookie coach Steve Lavin, who will coach St. John's in this year's Big Dance. Come March, however, the play is inescapable: Lewullis beating O'Bannon for the winning score.

"My son, who is 12 now, goes, 'Hey, dad, there you are again,'" says O'Bannon, who, like all of the UCLA players I spoke to about this game, was insightful, funny and none too bitter about March 14, 1996. Another clip gets played every March as well: Edney's 1995 buzzer beater against Missouri. "I have to remind him, 'Hey, there I am too," says O'Bannon. "To be a part of history in two different ways, that's all right by me."

I ask O'Bannon if he ever met Lewullis. No, he says. I was curious what he might say to him. "Why'd you do it to me?" O'Bannon replies. "How can you do it do me?" O'Bannon laughs. "I'd tell him, 'Great play.'"

And it's a play that Lewullis' coach, Pete Carril, doesn't love talking about that much anymore. "It's good for your health to forget about all those wins and all those losses," he says from his office in Sacramento, where he's a consultant for the Kings. "And keep your mind on what you're doing now." Sure, Carril is still thrilled that he went out on top back in 1996, though he quickly adds, "If we didn't have to play another game, and lose, it would have been better."

With another March Madness set for tip-off, Carril say he doesn't watch a ton of college hoops these days, though he does offer some advice for those teams trying to pull a Princeton. "It goes back to my high school days," he says. "You walked into the football stadium, and there was a sign there I never forgot: 'If you think you can't, you won't.' That's all there is to it. Know the strong points of your team, and your weak points, and what the other team is going to try to exploit. Hold onto your guts. Don't let them force you out of what you want to do. Of course, that takes a lot of mental courage. There's physical and mental courage, and we weren't very high on the physical part. But on the mental part, no one forced us out of doing what we knew we had to do to win."