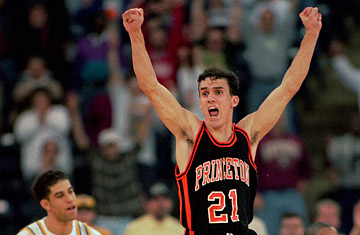

Princeton guard Mitch Henderson jumps in celebration of the Tigers' victory over UCLA in the first round of the 1996 NCAA men's basketball tournament

(2 of 6)

House Money

As the bus rambled back to Princeton, N.J., rolling over the eastern Pennsylvania steel country where Carril was reared, a bunch of college kids were belting out old saloon songs that didn't make a bit of sense. But the coach, a fountain of despair the entire season, was leading the joyous chorus. As he had written in the locker room of Stabler Arena on the campus of Lehigh University that evening, he was retiring. And he was happy. So we were too. And everyone cluelessly sang along.

No one had ever seen the guy this thrilled. After all, Carril was a man who would get so angry in practice that he would rip his shirt off, exposing tufts of gray chest hair to stunned 19-year-old kids trying not to crack up during the tirade. If you want to know why Princeton knocked off UCLA on March 14, 1996, start no further than the game five nights beforehand, a playoff against the University of Pennsylvania to determine the Ivy League winner. Penn was the three-time defending champion and had already whipped us twice that year. Though the final score of the first game, in January at Princeton, was 57-55, the result was deceiving. Toward the end of the game, we put together one of those typical college-basketball rallies that unfold when a team, knowing it has no real chance at winning, stops thinking too much and starts making crazy shots. In fact, with about a minute left, Carril, to my great surprise, threw me into the game; I immediately fired a three-pointer that, also to my great surprise, rattled in, helping ignite the futile comeback. (If you think I'm going to write all this stuff and not shamelessly mention the individual highlight of my college career, think again.)

Then, in early March, there would be no comeback. Princeton had a chance to clinch the title in the last game of the regular season, but Penn pounded us, 63-49, at the Palestra to force a playoff four nights later. Every slither of momentum favored the Quakers. "I was so nervous before that playoff game I thought I was going to throw up," says Steve Goodrich, our outstanding center who would later play pro ball for six years in Europe and even earned a brief NBA stint, with the Chicago Bulls and New Jersey Nets, in the early 2000s. "I couldn't get the f---ing butterflies out of my stomach. I felt so sick, thinking there was a possibility we were going to blow this whole season."

Carril shuffled the lineup for the playoff, inserting Lewullis and guard Mitch Henderson, our most athletic player, into the starting five. The move worked: Lewullis helped hold one of Penn's top scorers, Donald Moxley, to 0-14 shooting, and Princeton eked out a 63-56 overtime win. So the bus ride back to campus was incredibly cathartic. Selection Sunday was the next evening, and we all gathered in the room of senior Chris Doyal, our starting power forward, to discover our opponent. Everyone just wanted a plane trip that could almost serve as a spring break. When UCLA, a fourth seed, popped onto the screen, followed by Princeton, the 13th seed, the room roared. We'd be getting that trip — Indy might as well have been Cancún. Lewullis said, sarcastically, "So, it looks like we've got Mississippi State in the second round."

Preparing to play the defending national champions was kind of surreal. "I mean, Charles O'Bannon is going to be guarding me!" Lewullis said one dinner after practice, referring to the UCLA forward and younger brother of Ed O'Bannon, who was most outstanding player in the 1995 NCAA tournament as a senior. Benchwarmers like me served on the scout team, whose job was to mimic the opponent's offense in practice. We were certainly impressed with UCLA's personnel, but not scared. "We were so carefree," says Johnson. "Just playing with house money. And we knew we were good. We were like, 'Yeah, we know UCLA. They're good, but we'll just go out and play.' It was almost like not having an awareness of what we were against. That was a hell of an advantage."

All season, we had played a man-to-man defense. For this game, however, Carril decided we'd forsake all offensive rebounds. "I said, 'Don't go for any offense rebounds because you're not going to get any,'" Carril remembers. He told us to sprint back into a tight zone. "It was, 'Hold your follow through, maybe,'" says Brian Earl, a freshman sharpshooter who would go on to hit more three-pointers than any other player in Princeton history. Earl is now one of Johnson's assistants at Princeton. "You were in trouble if you didn't run back on defense. Whoever makes it back to the line first wins a prize."

This strategy, the thinking went, would slow down UCLA's potent fast break, and force the Bruins to beat us with outside shooting. "It was this crazy thing we concocted," says John Thompson III, now the head coach at Georgetown University, who was a 30-year-old volunteer assistant coach for the Princeton team. His Georgetown Hoyas will play the winner of the USC–Virginia Commonwealth play-in game in the opening round of this year's tournament. "And make no mistake: to be playing one way on defense the whole year, and then change it that late in the game, we were taking a risk," says Thompson. "Coach Carril made a gutsy call."

Most teams spend weeks perfecting their zone defenses. We had two days. "I remember [assistant coach Bill] Carmody cussing me out because I didn't understand where to slide in the zone," says Johnson. Carmody would take over as Princeton coach the next season; he's now the head coach at Northwestern. "I asked, 'What if a UCLA guy drops here?' And he started yelling at me, 'Other guys have figured it out! You figure it out!'"

Yet it was notable that while we were learning a knuckleball defense on the fly, UCLA was complaining about its seeding. Jim Harrick, UCLA's coach in 1996, still thinks his team got hosed by the selection committee. "If I talk about it, people are going to say I'm sniveling," says Harrick from his home in Southern California. "I'm really not sniveling, but I am. But I'm not sniveling behind the scenes." Harrick points out that Arizona, which finished behind UCLA in the Pac-10 standings, played in Tempe, Ariz., for its opening rounds that year. But UCLA, the league champs, was forced to fly east. Harrick suspects that Bob Frederick, the athletic director at the University of Kansas who led the tournament-selection committee that year, did not want his school, which was seeded in the West Region, to share a bracket with UCLA. In December, the Bruins lost to Kansas in Lawrence, Kans., 85-70, but Harrick believes Kansas still feared UCLA. "You may think my thought process on this is strange, but crazy things have happened," says Harrick. (Frederick died, after a bicycle accident, in 2009).

The Bruins had other problems. "There was just a lot of chemistry-type issues about who was going to be the star," says Kris Johnson, the son of former NBA player and UCLA star Marques Johnson, and a sophomore forward for UCLA. "I can't say we were the most focused team going into the tournament. We kind of went into it like, 'Ivy League, schmivey league.' It was a total 'whatever.' What-ever."

In other words, UCLA arrived in Indianapolis embittered, a bit disinterested and contemplating conspiracies. Princeton, on the other hand, was soaking up the scenery. Everyone was geeked up that a police escort accompanied us from the Indianapolis airport to our hotel, which was a good half hour from downtown Indy and under construction; that's the price you pay for being a lower seed. During the Ivy season, the only cops we saw on postmidnight bus trips through New England were those chasing down the long-haul truckers ready to pass out.

At the RCA Dome, Carril and a few of our players conducted a genuine press conference. "There was like a dais," says Steve Goodrich. "We were used to being in the basement of Jadwin [Gym, Princeton's home court], talking to, like, [former Trenton Times beat reporter] Mark Eckel. There's a different level of national media and stuff, and that was certainly a first for us. We got these pins that got you access to stuff, the ball was different, your school's name is on the banner for the regional. I mean, I took two days off from school every year to watch the first two days of the tournament. It was the dream. It's what you play for."

After playing in bandbox Ivy League gyms for the past two months, taking the floor of the RCA Dome, home of the Indianapolis Colts, was breathtaking. The locker room seemed like a mile from the court. Jaws on the floor, we gazed into the cavernous upper deck, realizing that basketball should not be played in a 60,000-seat football stadium. "It was like trying to shoot in a park out in the woods," says Brian Earl, then Princeton sharpshooter. "There was no depth perception. I was nervous about that because we weren't going to be doing a ton of driving to the basket."

The day before first-round games, the NCAA opens shootarounds to the public, at no cost. These sessions, which last an hour for each team, almost always turn into dunking exhibitions. UCLA went before us and gave the crowd an air show. Then we came out and opened up practice with our usual drill, called "star passing." This drill essentially required the team to stand in a circle around midcourt and toss the ball around for five minutes; this must have been the sort of drill that seemed cutting edge for the students of James Naismith, the PE teacher who founded basketball in 1891.

Talk about a letdown for the fans. After a few more minutes of mind-blowing dribbling up and down the floor, we formed a layup line! We had a few guys who could dunk; Carril, however, would hold an eternal grudge if you dunked in warm-ups but failed to grab a loose ball during practice or the game. So trying a slam wasn't worth the risk. Princeton forward Chris Doyal, however, was a senior who no longer cared about angering Carril, with whom he had clashed for four years. The floor felt springy, so the husky forward barreled in for a baseline dunk.

"I'll never forget the f---ing sarcastic clapping," says Goodrich. "We were [at] the last practice of the night, it was late, and the defending champs has just come on and put on a show. Everyone was leaving, and about four people stuck around to see, 'Oh, what do these guys do?' And I just remember these four people clapping in an amused fashion."

No one figured that 24 hours later, the cheers would be anything but a joke.