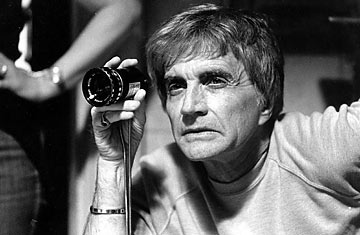

Film maker Blake Edwards on set in 1982.

In his half-century and more in movies, Blake Edwards never won an Oscar. His brand of film comedy, which earned him hosannas from such distinguished critics as Jean-Luc Godard in France and Andrew Sarris in the U.S., was too dry and strenuous for Hollywood's arbiters of high taste. But in 2004 the Motion Picture Academy did vote him a Life Achievement award, presented by Jim Carrey. Cut to the wings, where Edwards is seated in a motorized wheelchair, his left leg in a cast. Suddenly the wheelchair scoots madly across the stage, crashing through a pasteboard wall and taking its passenger with him. Tragedy on Oscar night!

Actually, it was comedy in the Edwards style: infantile and erudite, physical and cerebral, an appearance of anarchy that is meticulously planned and executed. The writer-director was fine, and anyway a stuntman took the wild ride. The wheelchair gag, which served as a middle-finger salute to Academy propriety, could have come from any number of Edwards movies: the Pink Panther films with Peter Sellers; or such comedies of sexual obsession and reversal as "10" and Victor Victoria, starring his second wife, Julie Andrews; or The Great Race, The Party, A Fine Mess and his other tributes to silent-era slapstick. Sixty-two years after he made his movie debut, at 20, as a cadet in Ten Gentlemen from West Point, Edwards was proving to the Oscar burghers and a TV audience in the hundreds of millions that he was still a kid at heart.

And when he died Wednesday night, at 88, of pneumonia in Santa Monica, Cal., with Andrews and their children by his side, Edwards might have boasted that he never did grow up.

Yet he did not always take his cue from Thalia, the muse of comedy. In his early prime Edwards was a jack of all genres and master too. He directed the wistful 1961 anaesthetizing of Truman Capote's Breakfast at Tiffany's, with Audrey Hepburn as the lady-tramp Holly Golightly. The next year he directed two intense dramas: the killer thriller Experiment in Terror, with Lee Remick as the bait for sicko Ross Martin; and the soberer, more piercing Days of Wine and Roses, JP Miller's tale of a middle-class couple, Remick and Jack Lemmon, on their descent into alcoholism from which only one surfaces at the end. ("You and I were a couple of drunks on a sea of booze," Lemmon tells Remick, "and the boat sank.") These three were among the few films Edwards directed that he did not also write or cowrite; Days of Wine and Roses was one of his very best.

CRUMP TO DIAMOND TO GUNN

Edwards's first laugh — a real scream — came on July 26, 1922, the day he was born as William Blake Crump in Tulsa. When he was four, and now in Los Angeles, his mother married Jack McEdwards, an assistant director (who would work as unit manager on Days of Wine and Roses). McEdwards's father, J. Gordon Edwards, directed the original silent-screen vamp, Theda Bara, in 23 films from 1916 to 1919, including Romeo and Juliet, Camille, Cleopatra, Madame du Barry and Salome. Blake had the movies in his adopted blood. At 16, if you believe the legend (I don't), he was befriended in New York by the 23-year-old theater prodigy Orson Welles, who allowed the boy to drop a few lines into Howard Koch's script for the notorious War of the Worlds radio broadcast. Four years later he was under contract to 20th Century-Fox.