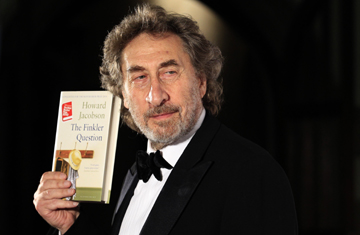

British author Howard Jacobson poses with his book The Finkler Question after winning the 2010 Man Booker Prize for Fiction at the Guildhall in London October 12, 2010

As a young British writer, Howard Jacobson wondered if he would ever be capable of winning the Man Booker Prize. And despite missing out on the award in previous years, the 68-year-old finally triumphed this week with his 11th fictional novel, The Finkler Question. Described by the chair of the Booker panel as, "very funny, of course, but also very clever, very sad and very subtle," the book has sparked a debate in the U.K. over the nature of the comic novel. Jacobson discussed the issue with TIME as well as his joy in winning.

You've had some narrow misses with the Booker Prize in the past and Tom McCarthy was favorite to win with his novel C this year. Were you pleasantly surprised when your name was announced?

I didn't know I had such a capacity for innocent pleasure left, I'm over the

moon. I have 500 emails at home, I didn't even know I knew that many people. I went into the ceremony very calm and things were sweet. America was waking up to this book on the back of a couple of very good reviews.

How do you respond to the suggestion that The Finkler Question is the

first comic novel to have won the Booker?

It's simply not true that my book is the first comic novel to win the Man

Booker Prize. Previous Booker winners Kingsley Amis, P.H. Newby and Salman

Rushdie absolutely presented novels of a rich comic tradition. I have said

in the past that the Booker doesn't favor comic novels. The misinterpretation this year is that I'm one of the first truly comic novelists to win, rather than The Finkler Question being the first comic novel to

win.

It's fantastically difficult to define the comic novel: what I may think is funny, others may not. I think it's difficult in the main for comic novels to win prizes because comedy is an upsetting thing. To win a prize you have to have a panel of people who will agree and people rarely agree on comedy. No one says that about a serious novel, no one questions how serious it is. Comedy makes people disagree more than any other form so therefore there will always be a debate.

Do you think the novel is suffering because of social networks?

I used to be a teacher of literature and I taught whole books. In

England many people don't read whole novels anymore, they read chunks. I

know there are plenty of readers out there but there are also many who have

become lost to reading because of Facebook and Twitter and other social

networks. Blogs tend to portray the idea that writing is just an exchange

of opinion. People will blog something about a novel and say it's a load of

crap and they can be very abusive, when in reality all they are actually

saying is, 'I don't agree with you.' I wasn't brought up to interpret

literature such as Pride and Prejudice and Great Expectations as something I

should agree with.

Through social networks we are brought up to either agree or disagree with novels. The whole point of literature — of writing it and of reading it — is that it takes you out of the business of having an opinion. As humans, our opinions are the worst part of us and art is not about opinion, "If I have an opinion as a novelist, I have failed." D.H. Lawrence said that and I say that.

There is a rich history of Jewish humor: who were you inspired by?

People always suppose that I'm routed in the American Jewish tradition of

great writers such as Saul Bellow, Philip Roth and Joseph Heller but I was

always a very conventional English literature man. When I wrote my first

novel nearly 30 years ago, my reading was not Jewish American but

mainly the English novelists such as Charles Dickens, Jane Austen and Samuel

Johnson. They inspired me with their beautifully made sentences and

intelligent comedy and I tried to be those writers but I couldn't be those

writers. It was only when I realized that I needed to get my Jewishness out

a bit that I could write at all. I bring to the English novel a kind of

Jewish music.

Are you optimistic that winning the Booker could help promote the

fundamental seriousness of the good comic novel?

I hope the prize will first of all promote the fundamental seriousness of me

and there are signs of lots of interest in America. Literature's first job

is to entertain. There's a horrible idea out there in the world that

entertainment and good literature are enemies, and that if you want

entertainment you have to read some drivel by a celebrity whose had her

parts rearranged. As a result of winning, I want people to see the

comic novel and think, 'Wow, I might actually enjoy this.' They might

be thinking and dealing with complex and serious issues as they laugh but

wouldn't that be wonderful for all of us?