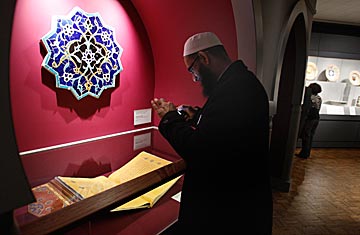

Imam Sohel Mangera photographs a Koran from about 1450-60, displayed at the Detroit Institute of Arts, part of the museum's new permanent gallery of Islamic art

Last week, the Detroit Institute of Arts opened its newest permanent gallery, one devoted to Islamic works. The collection, which features a Timurid Koran written on gold-flecked Chinese paper, and ceramic bowls from the 15th century Ottoman Empire, is a bold acknowledgment by one of the country's most venerable museums of the breadth of Islam's influence. It's also a test of whether the cash-strapped museum can tap into this region's relatively affluent Middle Eastern community, the largest in America.

To understand the new gallery's significance, consider the history of the DIA, as the museum is known in Detroit. Shortly after its founding in the 1880s, the DIA began collecting Islamic art. The 1920s auto-industry boom made Detroit one of the world's wealthiest cities — "the Paris of the Midwest," many called it. In 1927, the DIA moved into its current home, a white Beaux Arts building near Detroit's downtown, and sharply expanded its collections, mainly with European and American pieces, although it briefly hired an Islamic-arts specialist to curate a small collection. In the following decades, Detroit witnessed several key shifts: the emergence of a sizable black middle class and the arrival of Middle Eastern immigrants. But the DIA, which ranks among the country's top 10 museums, has largely remained the province of Detroit's white suburban élites.

In the late 1990s, the DIA hired Graham Beal, who formerly headed the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, to serve as its CEO. He arrived just as the DIA was set to launch a six-year, $158 million renovation and expansion. Beal's mandate: "to rethink how we present art to the general public." That meant tripling the amount of space devoted to the DIA's Native American art collection and opening a department to curate a collection of African-American art. Beal ordered that exhibit labels be more accessible to the masses. In one gallery, he added a virtual dining table, with porcelain and silver tableware, to offer a glimpse into the lives of 18th century French aristocrats.

Because of Detroit's disastrous past decade, the renovation took longer than expected, and the museum struggled: attendance, which is highly dependent on special exhibits, fell sharply. Last year Beal reduced the DIA's budget, from $32 million to $26 million, partly by laying off 20% of the museum's staff. Cultural sites nationwide are struggling to weather the economic crisis, but the challenge facing Detroit's institutions is especially severe; they can no longer rely on support from the region's ailing auto industry. Raising money, Beal says, "has been unbelievably challenging."

Still, Beal continued to push for an Islamic-art gallery. In the summer of 2005, he hired Heather Ecker, a well-regarded curator whose background includes a year at Qatar's Museum of Islamic Art. Ecker carefully combed the 900-plus pieces of Islamic art in the DIA's collection, most of which was stored in the basement. Some pieces, like shards of pots, weren't worthy of being publicly shown. Others were striking finds, like the massive gilded copper candlestick the DIA acquired from a Belgian art dealer in 1922. It had been classified as an 18th century candlestick but was actually made between 1400 and 1500 in what is now Turkey. Some people thought the candle looked like a church bell.

The gallery's nearly 170 pieces mainly concentrate on Islamic art from countries such as Spain and India. One room showcases sacred Muslim, Jewish and Christian texts. Last month a party marking the gallery's opening drew nearly 300 people, including many Muslim professionals from across the Detroit region. Many hadn't bothered visiting the museum before or hadn't spent much time there. "They didn't feel connected," says Ali Moiin, a prominent physician and the chair of the DIA's Asian and Islamic Arts Forum. The prevailing view, he adds, was, " 'There was nothing I wanted to see.' Now, they can say, 'I can relate to it.' "

Beal says reactions have largely been positive. But he has also been asked when he is going to open a Christian art gallery. His response: The museum has, in fact, two galleries devoted to Christian art. And Christianity is infused throughout the museum, especially in the European collections. Beal, who is fond of Islamic ceramics, says, "It's also important for non-Muslims to see this and understand the depth and beauty of Islamic art." His next challenge is to raise $1.5 million to open an Asian-art gallery.

The museum is slowly taking other steps to broaden its base of patrons to reflect Detroit's status as one of the country's most ethnically diverse regions. One example is the upcoming exhibit "Through African Eyes: The European in African Art." But some barriers remain. Sitting at a $20,000 table at the DIA's gala last November, a black socialite scanned the largely white room and sighed. Detroit has significant black wealth, she observed, "but it's hard getting them to participate."