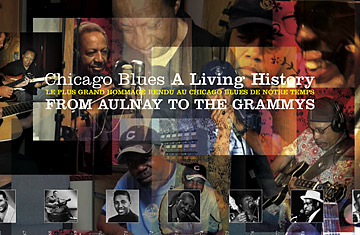

Cover of the Chicago Blues album 'From Aulnay to the Grammys'

Four years ago, the Parisian suburb of Aulnay-sous-Bois was in flames. The town was one of nearly 300 nationwide where housing projects exploded in rioting in October 2005 over dizzying unemployment rates, racial discrimination and a perceived exclusion from wider French society. When the deaths of two minority youths fleeing police in nearby Clichy-sous-Bois sparked violence there, residents of housing projects in Aulnay and beyond followed suit, venting pent-up rage by torching cars, vandalizing property and battling riot police for 20 straight nights. Ever since, most of France has viewed towns like Aulnay as being synonymous with restless youth and crime.

Now Aulnay is hoping to transform that image in a pretty remarkable way — by becoming the first city anywhere to win a Grammy Award, and one for American blues music to boot. This week, Aulnay officials announced that the town had been nominated for a Grammy by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences in the U.S. for the CD Chicago Blues: A Living History. The reason: town officials organized, co-produced and co-financed the 2008 recording, which features famous blues musicians like Billy Boy Arnold, Billy Branch, Lurrie Bell and John Primer paying tribute to the historical development and musical giants of the genre. Now that the CD has been chosen as one of four finalists for the "Best Traditional Blues Album" at the Jan. 31 Grammys, Aulnay suddenly finds itself on the cusp of musical history.

"Public attention and media treatment of Aulnay is always so dark and dismal that residents feel even more slighted and shunned than inhabitants of similar suburbs usually do," says Mohamed Beldjoudi, the town official responsible for cultural events, who was central to the making of the CD. "People feel like this Grammy nomination is finally a chance for Aulnay to be appreciated for its positive points. Even old ladies who don't care about blues are telling me 'This is just so wonderful!'"

So just how did Aulnay — a town of 80,000 about 10 miles northeast of Paris — become a mecca for the blues and a contender for a Grammy that's previously been won by the likes of B.B. King, Etta James, Eric Clapton and John Lee Hooker? It's in part due to the town's efforts to move beyond the violence of 2005 and find a different focus and identity for its inhabitants. One manner of doing that, Beldjoudi says, was to delve into and highlight the different cultural and artistic influences that generations of immigrants had brought to Aulnay over the years.

Initially, this involved showcasing traditional African music. But very quickly, Beldjoudi and his partners latched onto another idea: holding an annual blues festival to demonstrate how the uniquely American art form shares the same African roots as the types of music popular with Aulnay immigrants and their French-born children. After its maiden edition in 2007, the Aulnay All Blues festival became a major event, attracting some of the biggest American names in blues. Last year's event proved to be so popular, Aulnay decided to team up with blues producer Larry Skoller's France-based label Raisin' Music to recapture the magic on a recording. To do so, they arranged for the festival's featured musicians to lay down 21 tracks in a Chicago studio. Shortly thereafter, Chicago Blues: A Living History was released.

"We're just a humble little French town looking forward to a big evening in Los Angeles next month, but without any expectations," says Beldjoudi. "We're just hoping our association with this project will finally change the way people view the city and people of Aulnay." An image boost is a near given if Chicago Blues: A Living History wins its category (the town is up against Elliot Ramblin' Jack, the Mick Fleetwood Blues Band, John Hammond and Duke Robillard). But a Grammy probably won't turn the CD into a money-maker — even though it's been nominated for two other American blues awards, and has already won another pair in the U.S. and Europe, sales have yet to top 10,000 worldwide.

Beldjoudi says commercial success is secondary anyway. Aulnay's blues festival and the Grammy nod have already changed the way the city sees itself. Now, there's a possibility the rest of France will follow suit, transforming Aulnay's image in the public mind from the fiery, chaotic one that was formed four years ago.