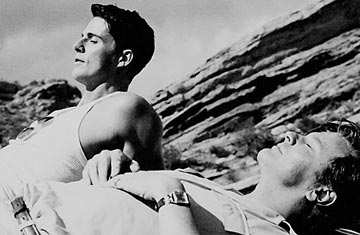

Still from Tom Ford's A Single Man, starring Colin Firth

The Toronto Film Festival ends its 34th annual session tonight, but most of the international press corps has gone home, their heads crammed with images and performances. Toronto, famous for years now as the kickoff to Oscar season, is the place Hollywood visits in search of Academy Award contenders. There were a few — though in a straitened economic environment, with fewer zillionaires eager to bankroll indie movies, some excellent films (Life During Wartime, The Joneses) had a tough time finding buyers. Crystal-balling the Oscars is fun, but it can't compare with seeing and savoring good films that might not be found elsewhere. Here's a rundown of five pictures worth chasing down — if they ever come to a theater near you.

A Single Man, directed by Tom Ford

For close to three decades, Colin Firth has been a reliable, gently charismatic leading man in the theater (Another Country), in movies (Bridget Jones's Diary) and on TV (as the dreamboat Mr. Darcy in the BBC's 1995 version of Pride and Prejudice). But until now, at 49, he never got that Role of a Lifetime that actors pray for. George, in Tom Ford's adaptation of the Christopher Isherwood novel, is it. The movie brought Firth the Best Actor prize at the Venice Film Festival and was bought for U.S. distribution by the Weinstein Company.

Firth plays an English novelist, teaching literature at a Los Angeles college in 1962 and grieving — delicately, obsessively, heroically — for his lover of 16 years, dead in a car crash. Seeing no reason for his life to go on, George meticulously rehearses his own suicide, by gunshot, but has trouble finding a practical or aesthetically elegant way to carry it off. So over the course of a long day, he listens idly to his colleagues' worries over the Cuban missile crisis; has dinner with his oldest friend, a London socialite (Julianne Moore, never more glamorous); and indulges some erotic flattery from one of his students (Nicholas Hoult). All these are distractions as George prepares for death in the manner of a samurai or Roman Senator, and bathes in memories of his precious Jim (Matthew Goode — Ozymandias in Watchmen)

Ford, the Austin, Texas, fashion designer who for a decade was the creative director at Gucci, financed his first feature himself. The director turned out to be a good investment for the producer. Nuance, not flash, is his forte. Playing to Firth's subtleties, he photographs the actor's handsome, mourning face in caressing close-up. (In his professor glasses, Firth looks like a young, more studious Michael Caine.) Ford is also attentive to the varieties of Southern California sunlight, which lends A Single Man an orangey warmth that should touch all who see the picture. But it's Firth's performance, as a man bereft, for whom solitude is a life sentence, that will win audience's hearts. Don't be surprised if he earns an Oscar nomination to match his victory in Venice.

Lebanon, directed by Samuel Maoz

Each year, in its City to City program, the Festival highlights a foreign cinema; and when TIFF chose Tel Aviv as the 2009 city, controversy erupted. "Tel Aviv is the military center of Israel," said Canadian author Naomi Klein, "a place from which fighter jets departed on their missions to Gaza last December-January." Soon it was mandatory for politically active stars to take sides. Sacha Baron Cohen, Jerry Seinfeld, Jon Voight and Oprah Winfrey voiced their support for the program; Harry Belafonte, Julie Christie, Jane Fonda and Viggo Mortensen were all for a boycott. Politics aside (which it never is at a film festival), the protesters ignored Israel's recent emergence as a vital national cinema — and that many of the country's prize-winning films, from The Band's Visit to Waltz with Bashir, take a complex humanist approach to Arab-Israeli relations. That is certainly the case with Samuel Maoz's Lebanon, which won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival and was one of Toronto's unarguable hits.

Like Bashir director Ari Folman, Maoz served in the 1982 Israeli-Lebanon war; his film is a survivor's haunted memory of that conflict. Except for the opening and closing shots of a field of sunflowers, the entire film takes place in an Israeli tank holding four very nervous soldiers. The only view to the streets outside is through the gunsight aimed at insurgents and civilians. Which ones to shoot at? Which ones to save? Imprisoning the audience with the soldiers may be a gimmick, but it's an inspired one: the viewer wants both to stay inside — shielding them from harm, or from doing harm — and to get the hell out. The situation may be familiar from dozens of Hollywood foxhole dramas, but the treatment is original: What other movie has, as its exalting emotional climax, the spectacle of one man helping another to pee into a tin can? Working as a horrors-of-war screed and a depiction of men under impossible stress, Lebanon is a salutary, unrelentingly claustrophobic nightmare.

Life During Wartime, directed by Todd SolondzThe central scene in Todd Solondz's 1998 drama Happiness was a bedroom conversation between a man and his 11-year-old son. Because the boy was frustrated that he hadn't achieved his first orgasm, and the father was a child molester, it hit audiences like a jolt of electroshock therapy. Eleven years later, Solondz returns to this extended family — three sisters and the men and kids in their lives — but with a new cast.