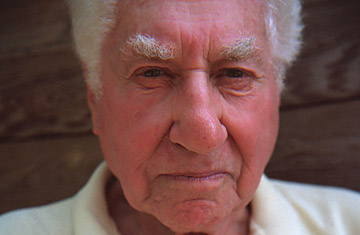

Author and Screenwriter Budd Schulberg, 88, at his home in Long Island.

Marlon Brando's in the back seat of a taxi with Rod Steiger. One man is a dockworker and former prize fighter, the other his older brother Charley. "Remember that night in the Garden?" Brando says. "You came down to my dressing room and you said, 'Kid, this ain't your night. We're going for the price on Wilson.' You remember that? 'This ain't your night'! My night!? I coulda taken Wilson apart! So what happens? He gets the title shot outdoors on the ballpark and what do I get? A one-way ticket to Palookaville! You was my brother, Charley, you shoulda looked out for me a little bit. You shoulda taken care of me just a little bit so I wouldn't have to take them dives for the short-end money." Steiger says, "Oh, I had some bets down for you. You saw some money." And Brando replies, "You don't understand! I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I could've been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am, let's face it. It was you, Charley."

Budd Schulberg was most certainly a somebody who did a lot of writing over a career that spanned Hollywood's golden age and ended Wednesday with his death at 95, but none of his words packed a punch quite like that legendary exchange from On the Waterfront, the 1954 dockside drama he wrote for director Elia Kazan. In 2005, the "contender" line was chosen as No. 3 on the American Film Institute's list of the 100 greatest movie quotes, right after Clark Gable's "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn" from Gone With the Wind and Brando's "I made him an offer he couldn't refuse" from The Godfather. In an earlier AFI poll, On the Waterfront was named the eighth greatest American movie of all time.

On the Waterfront was seen as both a bold exposé of racketeers and a defense of those film people, such as Schulberg and Kazan, who had named former colleagues as Communists before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. The film won eight Oscars, including Best Picture, Director and Actor (Brando) and Schulberg himself would win one for Best Writing, Story and Screenplay. He was the second-generation moviemaker and self-described "Hollywood Prince" whose most memorable work anatomized corruption in the more rapacious forms of entertainment: boxing (The Harder They Fall and it should be noted that Schulberg was former chief boxing correspondent for Sports Illustrated), TV and radio (A Face in the Crowd) and the movie business itself (his 1941 novel What Makes Sammy Run?). Two 1940s books and a few '50s movies may seem a small canon of work for a writer who lived so long, but Schulberg's oeuvre had an immediate impact and a lasting legacy.

Budd Wilson Schulberg was born in New York on March 27, 1914, the son of Benjamin Perceval (B.P.) Schulberg, who became the production boss at Paramount, the most glamorous of the young studios. For Budd, as he wrote in the memoir Moving Pictures, Hollywood "was Home Sweet Home, a lovely place to play with lions and alligators, to ride my bike down lanes of pine and pepper trees, and to make lemonade from my own lemon tree." While B.P. rode herd over Cecil B. De Mille and Ernst Lubitsch, Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich, the teenage Budd enjoyed the attention of his father's sexy stars. Clara Bow, the It Girl of silent pictures, ran her fingers through the boy's hair and even suggested they go out partying.

B.P. and his wife Adeline Jaffe, a literary agent, were rare New Deal Democrats among conservative moguls like Louis B. Mayer and unreconstructed primitives like Harry Cohn; and Budd extended their liberalism into membership in the Communist Party. After graduating from Dartmouth College in 1936 and returning to Hollywood, he was placed on the board of the new Screenwriters Guild to agitate for Party causes. He also worked on some B movies. On Winter Carnival (1939), a fictionalizing of the annual Dartmouth frolic, his co writer was F. Scott Fitzgerald, cadging for jobs in California after the drying up of his first act as the chronicler of the Jazz Age. Fitzgerald would die in 1940, leaving his Hollywood novel The Last Tycoon famously unfinished. Schulberg took the inside-movies notion, ran with it and produced What Makes Sammy Run?