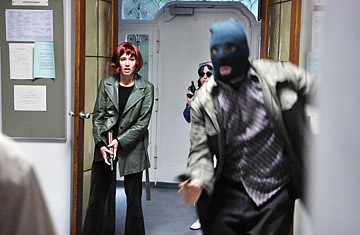

Germany's terrorist group, the RAF, in action in a still from Bernd Eichinger's film The Baader Meinhof Complex.

Among Hollywood's money men, German film producer Bernd Eichinger is known as the guy who signs the checks for big budget crowd-pleasers like Resident Evil and The Fantastic Four. In Germany, he's better known for his reputation as a maverick, a troublemaker known for partying and the occasional barroom brawl. A tall rail of a man with graying hair and a raspy smoker's voice, Eichinger stunned moviegoers everywhere with Downfall, the 2004 Oscar nominee that focused in shocking detail on the final days of Hitler and his cohorts in the tight quarters of the Führer's underground bomb shelter. Long before then, his first big commercial success in Germany was the 1981 film We Children From Bahnhof Zoo, the story of — another shocker — a 12-year-old girl in West Berlin who gets hooked on drugs and becomes a prostitute to support her heroin habit.

So when Eichinger set out to make The Baader Meinhof Complex, about a group of 1960s radicals who carried out a 30-year campaign of bombings, killings, and kidnappings in Germany, it was clear that he would tell the tale with the subtlety of a sawed-off shotgun. "I wanted to make a movie about what they did," says Eichinger. "I'm not interested in the psychology, in the Freudian aspect of this at all. I am not trying to prove a point. I want to demystify them." (See pictures of animated movies, including Waltz with Bashir, the favorite for Best Foreign Language Film)

More than 2.4 million Germans saw The Baader Meinhof Complex when it came out, to mixed reviews, last September, and now it's in the running for Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars on Feb. 22. Directed by Uli Edel — who called the shots on Eichinger's first hit — the film focuses on West Germany in the '60s, when a group of largely middle class youth led by Andreas Baader, Ulrike Meinhof and Gudrun Enslin broke off from the massive anti-Vietnam War student protests and, calling themselves the Red Army Faction (more commonly known outside Germany as the Baader-Meinhof gang), went on a killing spree in a fight against the establishment. "This is the story of our generation," says Stefan Aust, former editor of news magazine Der Spiegel and author of the book upon which film is based.

Told in a staccato beat of bombings, shootings and car chases, it's the story of a time when the young West German democracy, some 30 years after the death of Hitler, was shaken to its core. It was a high drama game of cat and mouse: The terrorists would act and the state would react with laws that many Germans felt curbed civil liberties, helping lift the Baader-Meinhof members to mythical status. It's a uniquely German story, but in the age of Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib, many of the themes also resonate with American audiences. "Eichinger has demonstrated that it is possible to treat stories that are inherently German in film in a way that they are interesting for people in other countries," says Alfred Hürmer, president of the film industry jury that picked Baader Meinhof as Germany's entry for the Academy Awards. "He's learned a lot from American films and has found a language in his films that is universal."

And what he's learned, he puts into practice himself. Eichinger is hands on, erasing the boundaries between producer, director and screenwriter — in 30 years of moviemaking, he's attached his name to more than 70 films. As he did for Baader Meinhof, he often writes the screenplays for the films he works on and gets involved in every detail. While writing Baader Meinhof, Eichinger spent months researching the gang, reading original transcripts of interrogations and court proceedings as well as coded messages written by imprisoned members to their supporters outside. Much of the material comes from Aust's book and the original documents the author turned up in his own research. "In addition to the book, [Eichinger] read a lot of other material and kept asking people to get him more," says Aust.

This obsessive research is all part of Eichinger's technique: to fill in the blanks of events that have entered Germany's collective consciousness, but that few people have witnessed up close. Baader Meinhof is laced with exact replicas of iconic photographs that appeared in German newspapers at the time. But these are the after-the-fact images of dead bodies and devastated buildings. Eichinger provides the missing frames, reconstructing the violence leading up to those images to expose its brutality.

His criticism of other German filmmakers who've tackled the same subject — such as Volker Schlöndorff in his 2000 film The Legend of Rita — is that they focus too much on trying to understand the terrorists and not enough on comprehending the destruction they caused. Besides, destruction makes for more exciting viewing. Throughout his career, Eichinger has emulated filmmakers who know how to entertain, which serves him well at the box office, but puts him at odds with the arthouse crowd, who accuse him of pandering. Never one to stand down from a fight, Eichinger bats the criticism back as a challenge. "Everybody would like to make popular films," he says, barely suppressing a grin. "The question is whether you're up to the job."