Reading on the Rise: A New Chapter in American Literacy

National Endowment for the Arts

January 12, 2009

The Gist:

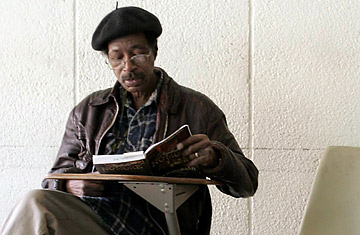

"New NEA Report Says Reading Is Up. And Hip," the Los Angeles Times proclaimed after the National Endowment for the Arts released its 2008 survey on the number of adult Americans who read literature (defined as any novel, short story, poem or play in print or online). For the first time since 1982, the survey reported a rise in the number of people who picked up a book or downloaded some prose — almost 16.6 million more since its 2002 census.Highlight Reel:

1. On what Americans are reading: The NEA's survey, which included more than 18,000 respondents, found that nearly 47% of all adults in the U.S. read a work of fiction not required for work or school in 2008, with the number of Americans who read a book growing by 3.5 million. (Of course, it should be noted that the general population has grown by 19 million since 2002, meaning that far more people in the U.S. opted not to read a book last year). A new question attempted to break the fiction genre down by subcategories — mystery, thriller, romance, science fiction, etc. — but with limited success: 46.3% of respondents prefer mysteries, while 40.8% prefer "other fiction." Poetry seems to be the most imperiled form of literature, largely because the number of women who read it — historically the genre's biggest fans — has fallen by 39% since 2002.

2. Comparing then and now: In 2004, following the NEA's publication of Reading at Risk, a report on its 2002 survey that identified a downward trend in American literacy, critics attacked the agency for publicizing "alarming national survey results." Evidently the NEA views its latest report as a validation of its efforts. "Our belief, then and now, was that the first step towards solving a problem was to identify and understand it," the agency's chairman, Dana Gioia, says in the report's preface. One of the most significant areas of progress involves the reading habits of young adults (ages 18-24), who went from a 20% decline in literary reading in 2002 to a 21% percent increase in 2008. "We note their progress with particular satisfaction," Gioia writes before giving itself a hearty pat on the back for promoting the change through programs like "The Big Read," which now has more than 21,000 organizational partners across the nation that sponsor book clubs and reading discussions.

3. On the causes of the rise: After hailing the results of its latest survey, the NEA's chairman asks the obvious follow-up: "What happened in the past six years to revitalize American literary reading?" His answer is disappointing: "There is no statistical answer to this question." Not one to let the absence of facts spoil a good story, Gioia then goes on to propose that perhaps the sheer volume of electronic entertainment and communication we're exposed to has created a backlash of sorts, prompting a reading renaissance. But as L.A. Times reporter Carolyn Kellogg points out, is it really accurate to consider laptops as "anti-literature?" Might the Internet be the answer and not the problem?

The Lowdown:

"Cultural decline is not inevitable," Gioia concludes. "While we cannot be complacent, we can surely pause to celebrate our common success." Unfortunately, that self-congratulatory tone spoils the entire report and overshadows its larger point — that more Americans reading is a good thing, regardless of whether the NEA made them.

The Verdict: Toss