Voluntary Madness: My Year Lost and Found in the Loony Bin

By Norah Vincent

Viking; 304 pages

The Gist:

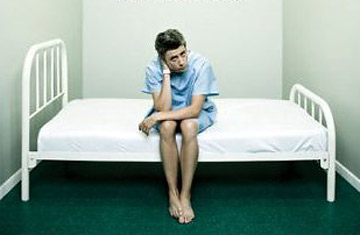

In 1887, New York World reporter Nellie Bly went undercover in a New York City mental asylum. Her shocking reports were eventually collected in the book, Ten Days in a Mad-House. In 2008, Norah Vincent planed to do the same thing, although in a vastly different manner.

Vincent had been in a mental institution before. While finishing her previous book, Self-Made Man—in which she went undercover as a man for more than a year— Vincent was overcome with depression, lost touch with reality and checked herself into a psychiatric hospital. The experience was not a good one (what visit to the loony bin is?), and so Vincent set out on a new endeavor: cataloging her experiences in three different mental institutions to find out what mental health care in America is really like. She visited an inner city hospital, a rural hospital, and a private alternative treatment rehab facility. To gain access, Vincent, like Bly, had to fake the crazy. This time, though, her act became reality. (See the Year in Health, From A to Z)

Highlight Reel:

1. On madness: "Maybe you, the normal man, walk into the kitchen in the wee hours and eat jelly by the tablespoon right out of the jar, and have no memory of it in the morning, only the weird evidence in the sink. Or maybe when you wake, you turn to your wife and say, "I had the strangest dream last night. I was flying in a tiger suit over Wall Street and your mother was wearing a turban.

And she will nod at you understandingly, knowing the oddity and cogency of dreams. You get up and go to work, sit in board meatings. You are sane.

But a mad person will say the same thing in the middle of the day, all day long, and he will find it more convincing because it is unshakable after a shower and a cup of coffee. Is he wearing his subconscious on his sleeve, as he tells you (or usually himself, aloud) of tigers and turbans? Has his mind turned itself inside out, switched night and day, abstract photo and real?"

2. On psychiatry: "There are no diagnoses in psychiatry. Only umbrella terms for observed patterns of complaint, groupings of symptoms given names and oversimplified, and assigned what are probably erroneous causes because those erroneous causes can be medicated. And then both the drug and the supposed disease are made legitimate, and thus the profession as well as the patient, legitimized too, by those medical words going hand in hand to the insurance company: 'Diagnosis,' and 'It's not your fault.'"

3. On getting better: "I don't often feel like working or doing something that's good for my brain, but I try to push myself to do it nonetheless, because, as with physical exercise, I always feel better when I've done it...I resent the effort it takes to maintain relationships or meet the tedious obligations that family and friendships can impose, and yet I know that isolation is very bad for me. I know that my happiness depends, in large part, on human contact and intimacy. And so, as with everything else, I do it and reap the reward, or I don't do it and suffer the consequences."

The Lowdown:

Vincent's writing is clean and crisp; she takes her craft very seriously. And although a first-person peek into any institution will be colored by the narrator's perspective, the book focuses almost entirely on Vincent and her struggle to define her own illness. The nurses are watching her, the patients are bothering her, the doctors are locked in a power struggle with her. Vincent focuses so much on herself that the reader begins to mistrust the hospital observations she presents as fact. Are the nurses really that cruel, or is she just imagining it? The three treatment centers, hidden by pseudonyms and with very few identifying details, come across feeling like caricatures, the kind of stereotypical hospitals and psychiatric wards that appear in movies.

Vincent shines when she describes the illnesses of others that surround her. She writes of other patients with sympathy, compassion, and an understanding that comes with shared experiences. The book would have worked much better if Vincent forwent the gimmick of three shallow hospital stays for a single illuminating one. Unfortunately, that also would have ruined the book's entire premise.

The Verdict: Toss