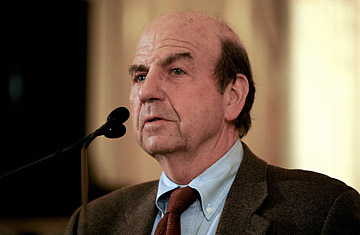

Writer Calvin Trillin

Calvin Trillin is part of that small, infuriating group of people who can write well about anything. During his half-century as a novelist, humorist and journalist — his first full-time job was covering issues of race at TIME's Atlanta bureau in 1960 — Trillin has penned dispatches on topics as diverse as Kansas City barbecue and finding parking spots in Manhattan, as well as acclaimed memoirs like About Alice, a remembrance of his late wife. Trillin's new book, Deciding the Next Decider: The 2008 Presidential Race in Rhyme, traces the campaign in verse.

Tell me about the process of writing this book. It wasn't your first effort at a project like this.

It's not my first effort at writing verse, but it was the first time I tried to write a long, narrative, epic poem. I somehow decided that doing a book of rhyming couplets would sort of drone on after a while, so I decided to interrupt it with what we're calling "embedded poems." Some of those — maybe about half — are poems that appeared in The Nation. The whole narrative poem is published for the first time in the book.

You used the word "epic." Do you consider this a transformative moment in our national politics?

Yeah, I do. It was not only an interesting race. I do think it was transformative. We're not out of the woods on all this stuff. But it means a lot.

In thinking about your attitude toward the campaign, the word that kept coming to mind was "bemused."

Yeah, well, the campaign was bemusing. One of the wonderful things about it is the people I've always referred to as "Sabbath gasbags" — the Washington people who appear on television on Sunday — were wrong, I guess, 100% of the time. They were almost never right. There were constant surprises. Who expected any of this stuff? It was only in looking back at it that you realized, hey, at one point this was going to be [Rudy] Giuliani vs. Hillary Clinton.

Can an election be transformative simply by virtue of its result, even when, in many ways, it was run traditionally?

It was transformative because of its result. We can break our arms patting ourselves on the back for electing the first African-American president, but in fact it means a lot. When I started working for TIME, it was in the South in 1960-61, and those were different times. If someone had told me at that point that we could have had a black president, I would have told him that he better not drive because he had had too much to drink.

For years you held one of the great jobs in journalism: traveling the country, filing a long dispatch from a different place every three weeks for a New Yorker feature called "U.S. Journal." I'm curious how you picked your story topics when the possibilities were pretty much infinite.

Sometimes that seemed like the most difficult part of it. I didn't go to a place; I always went to a story. The ones that worked out best were the ones in which the place was really the context for the story, and you learn something about the place as well. Finding the pieces was sometimes a matter of going to the out-of-town newsstand — which is probably closed by now — and buying a two-foot pile of newspapers from various parts of the country. Obviously reporters are always looking for stories with some tension and some narrative movement. I often found myself in places where one part of society was rubbing up against another. And then sometimes I'd sort of feel worn down by controversies and murders, and I'd look for a light story about a crawfish festival, or something like that. I don't think [New Yorker editor William] Shawn ever said, "No, that's not right for us."

How does that guiding philosophy of reporting — taking a subject and using it to tell readers about the way people live — apply to food, which is a topic to which you've returned many times?

The pieces I do about eating — and I still do at least one a year — are, to me, only interesting in that they're connected to American life. I don't cook. I don't know anything about food. I've never reviewed a restaurant. I think when I quit — about twenty years ago, before I took it up again — it was because it didn't seem like readers were getting that distinction. I'd get calls about, "Where's the third-best French restaurant in Chicago?" I don't have any idea, or even any credentials for deciding. I think my experience with people asking solemn questions about where the best this or that is shows how easy it is to be considered an expert in this country.

To what degree did media coverage of the campaign successfully illuminate the way people are? Or did the media rely too heavily on things like horse-race narratives?

Well, there's still a huge emphasis on the horse-race part, and I don't know if that will ever change. It's kind of a natural human condition: people are interested in who wins and loses. People, not just reporters, are more interested in politics than in government, so the actual issues wouldn't be something that interested them. What campaigns are for is weeding out the people who, for one way or another, weren't making it for the long haul. The fact that the Sabbath gasbags couldn't predict it is a good thing. People actually voted the way they felt like voting, rather than the way somebody told them they were going to vote. That's democracy.

You've done quite a bit of memoir writing. How difficult is it to turn your focus inward?

It's harder for me. I've written three books you could think of as memoirs. One of them was about a classmate of mine who was the person we thought would be President of the United States. He committed suicide. That led to a book about my father, since my father crept into the first book. Sometimes the memoir is painful to write, but then, I haven't written the sort of memoir that seems to be the style in the U.S. now, which I often characterize as an "atrocity arms-race." With the one about my father, I kept wondering why I was doing this. My father, for most of his working life, was a grocer in Kansas City. Why would anybody be interested in a Kansas City grocer to whom nothing really dramatic happened? Why would anybody want to read it? I only wrote the book about my wife after David Remnick, the [current] editor of the New Yorker, asked if I had ever thought about doing one. You're never quite sure what readers are going to take away from what you write. The book about my wife, to some people, was a book about love and marriage. I just wanted to write about my wife. I was on some television show, and I remember someone saying, "He shows he's in touch with his feelings." All I could think of was that I hope none of the guys I went to high school with read this. I'll never hear the end of it.