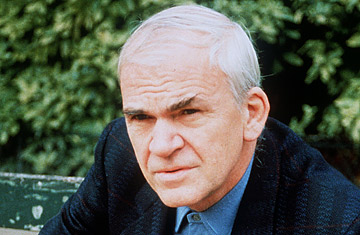

Author Milan Kundera.

Milan Kundera has not lived in what is now the Czech Republic for more than three decades, and some of his best works are still awaiting publication in his native country. But he is still regarded as one of the country's greatest writers and, more importantly, a leading voice of the generation that turned away from Communism to embrace the heady liberalismof the Prague Spring before it was crushed by Soviet tanks.

So the recent allegation that, as a student under Communist rule, he informed local police on a young man is being greeted with dismay, and a little disbelief. The author of The Unbearable Lightness of Being and other best selling novels has vehemently denied the allegation, saying that the allegations are an attempt at character "assassination" and that he did not even know the man in question — a Czech-born agent of a Western intelligence agency who was subsequently sentenced to 22 years in prison.Czechs are not so much shocked that Kundera, 79, now living in Paris, may have snitched on a suspected class enemy while a staunch Communist. Such things were not uncommon at the time. What most find surprising, however, is that the secret was kept for so long. At the same time, his supporters stress that any such incident should not detract from his work as an artist and could even explain the nature of his genius: his moral detachment and near-obsession with the themes of denunciation and betrayal. "I have always known [Kundera] was a Communist, a man who had believed the idea, " says Pavel Janousek, a literary historian at the Czech Republic's Academy of Sciences. "Something like this could not be ruled out. But he will remain a great writer. Only some of the themes that have been considered literary will be seen, additionally, as personal."

Jiri Zak, who translated some of Kundera's French writings into Czech, told the Czech news agency CTK that the reports were "a nasty and incomprehensible surprise" — not least because the accused spy was nearly sentenced to death — but that it would not alter his views of the writer's work.

"Everything that the writer lives through can somehow reflect in his work," wrote Czech novelist and playwright Ivan Klima, a contemporary of Kundera's in a Czech newspaper. "Perhaps only a subconscious need to come to terms with [an experience] can ignite the creation of great work. That is a paradox of creation and, in effect, of life itself." Speaking to TIME, Klima added, however, that while "any piece of biographical knowledge about an author can help in the interpretation of his work, it is not decisive." The Czech writer Jaroslav Hasek was " a drunk", Klima pointed out. "But he still wrote the work of genius The Good Soldier Svejk."The charge was made public by the Czech magazine Respekt and by the country's Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, a state-funded historical archive and research body. The magazine and the historical institute published a contemporary police document that names Kundera as the man who had informed police about the whereabouts of Miroslav Dvoracek, a former military pilot who had fled to what was then West Germany in 1949. Dvoracek signed up with a Western intelligence agency and returned undercover in 1950. Kundera, who had not spoken to the press for decades, broke that silence this week to deny the allegation, insisting he never even knew the spy, and that the alleged tip off "did not happen."

The confusion over the charge deepened still further on Thursday, Oct. 16, when a new charge surfaced in the Czech media that the informant was not Kundera at all but a friend named Miroslav Dlask, now deceased. A Czech literary historian, Zdenek Pesat, 80, released a written statement claiming that Dlask told him he informed the police about the whereabouts of Dvoracek. Reached by telephone, Hana Pesatova, the wife of Pesat (who is on a respirator and unable to talk) told TIME that her husband "remembers this clearly. Kundera was not involved. Dlask sought my husband out and told him this." She offered no explanation for why Kundera's name would have appeared in the police report.While not commenting on the accuracy of the allegation against Kundera, Czech historians suggest that presented with the context, the choice to expose a a suspected enemy of the state would have been quite widespread among Czech students of the time. "It falls within the context of that era," says Ondrej Tuma, director of the Institute for Contemporary History . "The Czechoslovak society, and especially the young people, the intellectuals, were crazy about the Communist ideology. They were absolutely serious about it, including the propaganda and spy-mania. Thousands and thousands of young people would have acted the same way."

At the time, says Tuma, such a denouncement was not even considered a betrayal. "[The informer] belonged to one side of the struggle and turned in an enemy," he said. "But he would have also known the consequences. Those people were convinced that the class struggle is tough," Tuma concludes. "When you are chopping down a forest, splinters fly." Dvoracek ended up spending almost 14 years in jail, mostly in a notorious labor camp, a uranium mine in Bohemia.

Among other things, the flap underscores the difficulty of gleaning the truth from communist- era archives. Police files similar to the one in which this document was found exist in most post-communist countries in eastern Europe. And such celebrated opponents of communism as former Czech President Vaclav Havel and Polish dissident journalist Adam Michnik have argued strenuously against their contents being divulged to the public, for fear that the information will be misinterpreted, used for political gain, or to carry out personal vendettas. Skeptics also point out that the communist-era police frequently forged documents to embarrass state enemies.

Still, the latest allegations against Kundera, which have spurred discussion across Europe, are a reminder of the moral ambiguities and compromises that haunt the generations that lived through World War II and the Cold War — exactly the stuff of the novels that made Kundera famous.