Steven Watts's Mr. Playboy: Hugh Hefner and the American Dream.

Mr. Playboy: Hugh Hefner and the American Dream

By Steven Watts

Wiley; 529 pp.

The Gist:

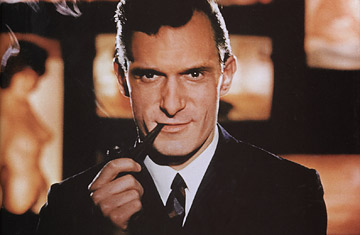

Any man who boasts a troika of girlfriends five decades his junior, pops Viagra like Pez and considers smoking jackets formalwear is bound to be divisive. But whether you consider Hugh Hefner a smut-peddler or a "prophet of pop hedonism"—TIME's phrasing in 1967—you can't deny the guy his place in the American canon. And in Mr. Playboy, biographer Steven Watts argues that Hef's influence extends well beyond the bedroom. By framing sex as an All-American aspiration—as worthy a pursuit as good wine or flashy cars—the famous free-love evangelist scrambled our social norms, "[loosening ]old-fashioned moral strictures on one of the most powerful of human urges."

Highlight Reel:

1. Hefner was reared in an Illinois household that avoided displays of affection, and he's often traced his turbo-charged sexuality to this repressive upbringing. As a child he was a loner, refusing to answer the telephone or make short trips by himself. Though an indifferent student, he flashed a glimpse of his entrepreneurial spirit early on by writing, illustrating and selling mini-newspapers and magazines at school and in his neighborhood.

2. Hefner's first real high-school love interest spurned him. "He saw [Betty Conklin] as the ultimate coed and they learned to jitterbug together, but when school started, she invited someone else to the hayride," Watts writes. Suffice it to say that the jilted lothario-to-be rebounded. Hef's fixation with sex sharpened after Alfred Kinsey released his famous 1948 study. The following year, he married his high-school sweetheart, Millie Williams. But he soon began bristling at the constraints of monogamy. Risque parties quickly gave way to experiments like wife-swapping (with his brother!) and even a one-time homosexual tryst.

3. Hefner considered Playboy (which would have been called Stag Party if not for a copyright snafu) a liberating force for both sexes. But naturally, some women questioned whether swapping aprons for lingerie constituted a net gain. After some 300 protestors organized by a Chicago women's group picketed the Playboy mansion in 1970, a female secretary leaked to the press a memo that underscored Hef's antipathy toward "militant feminists": "What I'm interested in is the highly irrational, emotional, kookie [sic] trend that feminism has taken...these chicks are our natural enemy. It is time to do battle with them."

Hef also clung to impossible double standards. If one of the girls he was juggling arrived home while he was otherwise engaged, his staff would cut the music piped into the mansion to alert him of her approach. Hef wanted his consorts to be spotlessly faithful, but when one of them insisted he do the same, the publisher would "stomp his feet and beat his pipe on the table and turn purple in the face."

4. "Our Puritan roots are deep," Hef told TIME. "We're fascinated by sex and afraid of it." Hefner didn't seem skittish; he indulged in it at every chance he got. Life at the mansion was lavish and lascivious—a Puritan's ninth circle of hell. Strolling grounds populated with imported squirrel monkeys, flamingos and llamas, dotted with waterfalls and full of celebrities, Peter O'Toole said: "This is the way God would have done it if he had the money." Adds a guest: "It was like going to some infant's paradise, where you could eat all the candy you wanted and you wouldn't get fat."

The Lowdown: Watts is intent on exploring the deeper meaning of Hefner's popularity and securing the publisher's place in America's cultural history. But he takes this admirable impulse too far. Nearly every chapter sub-section ends with a sweeping pronouncement: "Hefner and Playboy's social and political orientation in the early 1960s reflected a Kennedyesque sensibility," he writes in a typical summation. The effect can be grating—a magazine which calls the naked librarian gracing its pages "as dewy as a decimal system" cannot then be said to embody the Cold War ideological gulf demonstrated by Nixon and Khruschev's "Kitchen Debates." Hefner was a canny brand manager and a social visionary. He prodded the public to bare its darker desires—and in the process demystified sex for a generation. However, Watts may be inflating the impact of a man whose enduring legacy is a magazine often found stashed under teenage mattresses.

Verdict: Skim