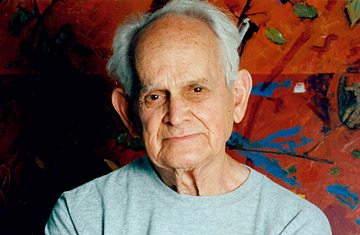

Artist Manny Farber

(4 of 4)

For a five-month stretch in 1949-50, Manny was employed as Time's Cinema critic. After The Nation and The New Republic, a Time stint meant a sharp raise in pay (he was hired at an annual salary of $8,500, a hefty sum back then) but a likely loss in status among the intellectuals whose favor he craved. He may have thought his work for the magazine was beneath his standard; Negative Space includes no Time reviews. I had guessed that the gig was painful, that editors rewrote his copy into Time-speak, with its backward-running sentences, space-saving but eye-irritating ampersands ("now & then"), capitalized job designations and film references shoved in as nicknames — "Director Elia (Gentleman's Agreement) Kazan" — often with the job title crushed into a compound cuteism ("Cinemactor Sessue Hayakawa," "Cinemogul Darryl F. Zanuck"). I assumed that, when Manny left the place, he felt well rid of it.

Yet he told me that he considered not making a go of the Time job the biggest failure of his writing career. One explanation is his rivalry with Agee. In that 1958 essay — a piece so conflicted it could have been called "Let Us Now Praise/Blame Little/Big Men" — Manny seemed to prefer the Time Agee to the Nation one: "Agee's Time stint added up to a sharp, funny encyclopedia on the film industry in the 1940s. Though he occasionally lapsed into salesmanship through brilliantly subtle swami glamour (Henry V, the Ingrid Bergman cover story), Agee would be wisely remembered for quick biographies and reviews, particularly about such happy garbage as June Haver musicals and an early beatnik satire Salome Where She Danced, where his taste didn't have to outrun a superabundant writing talent."

He had a similar opinion of my work (which I dare to compare to the elegant Agee's in no other way). While some friends figured I'd sold my soul by going to Time, committing weekly journalism instead of writing essays and books, Manny said he thought my Time stuff was better, freer and more concentrated. I suspect his comments on Agee and me spoke to an admiration for workmanlike salaried labor, whether done by carpenters, bottom-rung gangsters, tanktown vaudevillians, Poverty Row directors or movie critics. To him, Agee's and my "little magazine" essays were white elephants, our Time stories termites.

I also believe that Manny was in some ways simpatico to Time, even or especially in its early maturity. Both he and the Luce publication favored wordplay, luscious similes, extreme verbal concision (e.g., a string of adjectives without an "and" before the last one), abrupt shifts of tone, with gags that interrupted the serious analysis — all in the aid of entertaining as well as enlightening or pushing an agenda, and in recognition that getting people to read a magazine required a measure of variety-showmanship. Manny's earlier writing had many of these qualities (as well as many others that Time had little use or space for). That must be why he was hired — that and, I'll bet, Agee's recommendation. It could also explain why he wanted to be there.

What about Manny's Time writing? Since the magazine's entire archive is available on TIME.com, the Farber columns should be easy to find. But Time critics did not get bylines until the Vietnam years, so you can't just put "Farber" in the Search panel and call up his stories. You must delve into the bound volumes of the magazine in 1949 and 1950, where, for each review, the author's name is written in the margin. Thanks to the yeoman work of Arts maven Amy Goehner and ace librarian Bill Hooper, we have a firmer handle on Manny's Time work. We can't speak with certitude, since other names — probably the researchers', less likely other reviewers' — occasionally appear with his. When Polito compiles his Complete Manny Farber edition, we'll know for sure. For now, I'm taking on faith his authorship of all Time movie reviews from Sept. 12, 1949 to Jan. 24, 1950.

What Amy and Bill found were 15 columns of between 800 and 1,300 words, covering such pictures as White Heat, Germany Year Zero, Pinky, The Heiress, Beyond the Forest, Thieves' Highway, They Live by Night, All the King's Men, Intruder in the Dust, Passport to Pimlico (loved it) and Adam's Rib (hated it). You can locate these and other Manny movie reviews fairly quickly by typing a film's title, in quotes, into the Search box. What you'll also discover is a 32-year-old writer coping with a house style and deadline fatigue, but also fighting to get his say and his way and frequently winning. His advocacy of neo-realism, of storytelling efficiency, of teeming termite life in the corners of the film frame, and his excoriation of fussiness, bloviation, "artistic" movies, ring clear, as does his unique voice. Dozens of passages here could have been written only by Manny. I don't say his Time columns were near his best stuff, but a lot of it is choice.

At a lunch Manny had in 1977 with Film Comment's associate editor Brooks Riley and me, Manny allowed that, yes, he might be thought of as one of the 10 best film critics... Always competitive, and this time underestimating his worth. (A quick list of nine others, without overthinking it, but just going by the gut feeling of folks whose writing makes me jealous: Ferguson, Agee, Robert Warshow, Sarris, Kael, Richard T. Jameson, J. Hoberman — the best weekly film critic today, and the one who drank deepest at the Farber font — and, of the new guys, Ed Gonzalez, and honorary adoptive American, David Thomson.)

But, Manny said with matter-of-fact poignance, "what I'd really like is to be considered one of the 100 best American artists." This was just around the time he was segueing from large abstract paintings to his overview collages. I've seen Manny's paintings, but only as reproduced in a catalogue. And I'm no art historian. So I called upon the expertise of Richard Lacayo, Time's art critic and, not incidentally, a serious film connoisseur. Richard e-mails me that Manny "frequently did these bird's-eye views (I call them table tops) in which the whole canvas is filled with figures, houses, objects, photographs, all seen from above, and frequently (not always) connected by train track that carries your eye all around the canvas. They always struck me as being like his writing about movies, where he puts before you this world of bright particulars picked out by his magpie eye and connected by his very original train of thought."

I can testify to his originality in film criticism, and to his influence, certainly in the acceptance of the "male action film." Carrie Rickey called him "a man's man, and some of Manny's preference for Hawks and Walsh films over the warmer, daintier ones of, say, George Cukor, may reflect a man's impatience with women's problems and their need to talk about them. You could say his take prefigures today's movies, where women are absent or subservient and guys get to do guy things.

But Carrie is right in seeing Manny not as just a superb writer-reviewer, but the manliest, or Manniest, of them all. He approached film writing as a superior workman does a challenging job: total planning, total inspiration, hard work. And a respect for his craft. He was tough on other critics, and on himself, but he never demeaned the writing to which he brought so much passion and pain. "Criticism is very important, and difficult," he said in the Ollman interview. "I can't think of a better thing for a person to do." Surely no one did it better than Manny Farber.