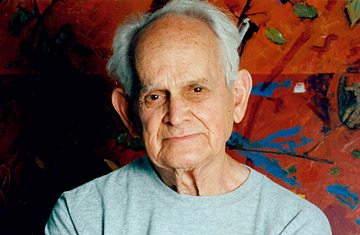

Artist Manny Farber

(3 of 4)

In the mining town of Douglas, Ariz., just above the Mexican border, Emanuel Farber was born on Feb. 20, 1917, youngest of a store owner's three sons. "I had two brothers who were fiendishly good at almost everything they approached," he recalled in the Art in America interview, "and they were fiendishly competitive." Both of his elder siblings became psychiatrists; one, Leslie, was a distinguished author. "And I had a father who was equally competitive." Farber, Sr., originally from Vilna, Lithuania, had studied to be a rabbi, and schmoozing must have been in the syllabus. "I picked up the congenial element of befriending important people from my father, way back."

In school, he said, he was the class clown. "I could never do the plot or the character descriptions. But if I could add to something with a joke, it would work.... If it seems funny to me to make a side remark while I'm discussing a serious subject — simply because of the sound of the words, or the sound of the thought — I think it's legitimate." He was briefly at Berkeley, then transferred to Stanford, where he took a drawing class. In his early 20s he went to Washington, D.C., where Leslie had a practice. There Manny took up the carpenter's trade. (When he visited us at Film Comment in the 70s, our office was in the American Bible Building; he remarked that he had worked on the building's construction.) Carpentry may have influenced his later collages and their element of compartmentalizing in squares. It also supplemented Manny's work as a critic — though, he professed to Ollman, he never acquired practical expertise: "I can't fix anything."

Otis Ferguson, one of the earliest film critics to create a coherent and eloquent body of work, was reviewing for the New Republic. "When Ferguson went off to the Coast Guard at the beginning of the war and was destroyed by a Nazi bomb, I immediately wrote a letter to the editor saying that I could do the job very well." He recommended himself for the film job over art criticism because, "doing movies, I would be in print every week. Doing painting I would be in once a month. I was getting $40 or $50 an article and that wouldn't be sufficient for getting us through life." He was at the time married to the first of his three wives.

At the New Republic, and then The Nation, Manny built his caviar reputation. By now he was in New York, pursuing his three careers, befriending the right people in the Abstract Expressionist world and in magazine criticism. (Can't say whether he also hobnobbed with the top carpenters.) Like an assiduous upward-achiever, he was trying to get noticed; he didn't succeed enough to suit him. Even in his late collages, Manny was craving the attention of the art-critical establishment. A scrap on his painting Batiquitos reads: "Heaven to be noticed by Roberta Smith or [Adam] Gopnik."

Over the decades he wrote for Commentary, Commonweal, The New Leader, Film Culture, Artforum — his most sustained affiliation, from 1966 to 1971 — and, just before that, for Cavalier. It's a mystery what the consumers of that second-tier girlie mag thought of Manny's column. He certainly wasn't trying to ingratiate himself with them; his prose was as gnarly as ever. Sample lead sentence: "What is interesting about the Cultural Exposition [Explosion?] is that while the public has become cognizant of the geniuses in each art form, the works themselves have been losing their identity as painting, TV comedy, or film." Maybe the Cavalier clientele really read it for the articles.

One of his more complicated friendships was with James Agee, who reviewed movies for The Nation and Time, had contributed the text to the Dust Bowl picture-poem Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and would go on to write the novel A Death in the Family and the African Queen screenplay with John Huston. (He also worked vagrantly with Manny on a never-completed script.) Agee was the alcoholic Episcopalian golden boy to Manny's cranky Jewish mensch, and that may have stoked jealousy and resentment. How was Manny to know that Agee, however lauded in his time (he died at 51 in 1955), would in the long run be the white elephant to Manny's termite? No, let's be fairer: Charlie Chaplin, equal parts genius and sentiment, to Manny's Buster Keaton, the deadpan acrobat and scene constructor, who had to wait ages for his star to eclipse Chaplin's in critics' eyes.

In 1952 Manny very favorably reviewed In the Street, a furtive documentary shot in Harlem by Agee, Janice Loeb and Helen Levitt: "Every Hollywood Hitchcock-type director should study this picture if he wants to see really stealthy, queer-looking, odd-acting, foreboding people." Six years later, considering the posthumous collection Agee on Film, Manny was less generous. The essay, "Nearer My Agee to Thee," alternates salutes and bitch-slaps so rapidly it seems simultaneously a military tribute and a Three Stooges routine. But that's par for a Farber piece. As Polito notes, he "sustains strings of divergent, perhaps irreconcilable adjectives such that praise can seem inseparable from censure — Touch of Evil, he writes, is 'basically the best movie of Welles's cruddy middle peak period.'"