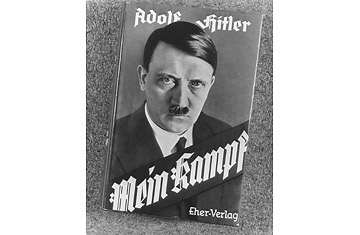

A front jacket to Adolf Hitler's autobiography, Mein Kampf, taken in 1924

It's long-winded and badly written, a tirade against all things non-German that would have disappeared if its author had never managed to turn many of his vile words into action. Adolf Hitler's notorious Mein Kampf (My Struggle), a manifesto posing as autobiography, has long been banned from German bookshelves "out of a responsibility and respect for the victims of the Holocaust." But 83 years after it was first published, some Germans argue it should be made available again in order to drain it of whatever power it might still have.

A debate over the book is slowly growing in Germany, in part because Mein Kampf's copyright, held by the state of Bavaria, will expire in 2015. Then the book will enter the public domain, and anyone will be able to reprint the text. Academics and officials who fear that a flood of new editions may be abused by far-right extremists are now demanding that a carefully researched and critical edition of the 800-page tome be prepared as a way to demystify it.

"We have to prepare our contemporaries for the release of Mein Kampf," urges Oscar Schneider, head of the board of trustees of Nuremberg's Documentation Center Nazi Party Rally Grounds. "We have to supply them with objective arguments and give them the ability to hold their own in the political and publicity debate." This, says historian Wolfgang Altgeld from the University of Würzburg, could be done through a step-by-step commentary of Hitler's hate-filled harangue that would also uncover "where he copied from others" and which elements of his life story "are pure fiction."

Even the Central Council of Jews in Germany has changed its zero-tolerance stance toward a German release of Mein Kampf. "An aggressive and enlightened way of dealing with the book would undoubtedly divest it of much of the myth that so unjustly surrounds it," says Stephan Kramer, the organization's general secretary. The "lack of comprehensive knowledge about the [National Socialist] regime" doesn't allow German youths to put the book "into context." A well-annotated edition is both "sensible and important."

But not every historian agrees. "There's simply no need for it," says Wolfgang Benz, head of the Berlin-based Center for Research on Antisemitism. Not only would such a learned tome "fail to add to our understanding of such things as the Holocaust or the elation with which many people followed the Nazi rule," it wouldn't even reach those supposedly benefiting from it: the man in the street. "Your average Joe just isn't interested in such a publication," Benz says. "At least, I haven't met anybody yet — in the subway or wherever — who has begged for one."

The argument that a critical edition would prevent abuse of the tract for far-right agitprop doesn't persuade critics of an un-banning either. "The text is easily available abroad and on the Internet," argues Jürgen Faulenbach from the Federal Agency for Civic Education in Bonn. "Nobody can prevent people from quoting it or using it for [illegal] purposes, and an edition like the one some people now call for won't change that."

In the end, any change will have to come from Munich, and so far decisionmakers there have suggested that's unlikely. Ever since it was entrusted with the copy and usage rights of Mein Kampf more than six decades ago, the Bavarian government has tried to prevent the dissemination of Nazi ideas at home and abroad by refusing permission for complete reprints. Intended "as a clear signal" against Nazi ideology, this restrictive attitude "will not be changed," according to a statement by the Finance Ministry responsible for it. The status quo is "generally respected and highly appreciated."

Whatever the outcome of the present controversy, one thing seems clear: the author himself would have been thrilled that his outpourings still have so much power to draw attention and stir up discord.